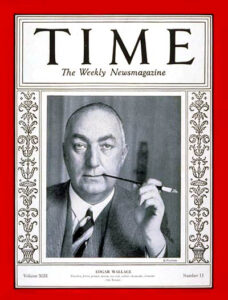

In the April 15, 1929 issue of Time magazine, Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace was called the “. . . purveyor of mass literature for King, commoner, and shopgirl.” He was featured on the cover of the magazine.

In the April 15, 1929 issue of Time magazine, Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace was called the “. . . purveyor of mass literature for King, commoner, and shopgirl.” He was featured on the cover of the magazine.

Born on April 1, 1875, Wallace was the illegitimate son of two itinerant actors. Adopted into a large family by a London fishseller and his wife, the future “King of Thrillers” was selling newspapers at age 11. He quit school the next year and began trying out various occupations.

After he turned eighteen, Wallace joined the Army and was shipped off to South Africa. Finding military life not to his liking, he bought his way out and began writing about the Second Boer War for Reuters and the Daily Mail. After the war, he returned to London as a crime reporter for the Mail, using “Edgar Wallace” as his byline.

Wallace’s first book was a collection of ballads, published in 1898. Seven years later he was inspired by a group of spies he met while reporting from Europe to publish his first mystery novel, The Four Just Men. Vowing to give his readers “crime and blood and three murders to the chapter,” his novel chronicles the exploits of a group of wealthy vigilantes who assassinate people committing clandestine crimes.

Wallace’s first book was a collection of ballads, published in 1898. Seven years later he was inspired by a group of spies he met while reporting from Europe to publish his first mystery novel, The Four Just Men. Vowing to give his readers “crime and blood and three murders to the chapter,” his novel chronicles the exploits of a group of wealthy vigilantes who assassinate people committing clandestine crimes.

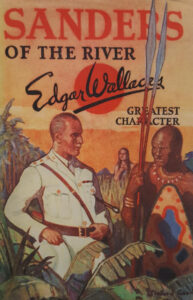

After traveling to the Belgian Congo on a newspaper assignment, Wallace was invited by The Weekly Tale-Teller to contribute a series of stories inspired by his experiences. These formed the basis for his collection, Sanders of the River, published in 1911 and later adapted into a popular film starring Paul Robeson and Leslie Banks. Wallace would write over 100 stories featuring Commissioner Sanders, Lieutenant “Bones” Tibbetts, Bosambo of the River, and other distinctive characters. These formed the basis for 11 collections and one novel.

After traveling to the Belgian Congo on a newspaper assignment, Wallace was invited by The Weekly Tale-Teller to contribute a series of stories inspired by his experiences. These formed the basis for his collection, Sanders of the River, published in 1911 and later adapted into a popular film starring Paul Robeson and Leslie Banks. Wallace would write over 100 stories featuring Commissioner Sanders, Lieutenant “Bones” Tibbetts, Bosambo of the River, and other distinctive characters. These formed the basis for 11 collections and one novel.

While still working as a newsman, Wallace increasingly turned to fiction to help make ends meet. In addition to the Sanders yarns and other stories for The Weekly Tale-Teller, he turned out tales concerning everyday life in the British military for the Daily Mail. These were collected into four volumes published from 1905 – 1916. Wallace’s byline could also be found regularly in The Grand Magazine, The Novel Magazine, The Pall Mall Magazine, The Red Magazine, The Royal Magazine, The Story-Teller, The Strand Magazine, The Windsor Magazine, and other British periodicals.

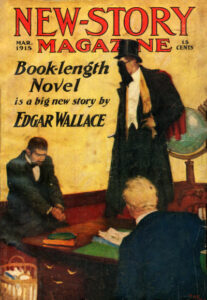

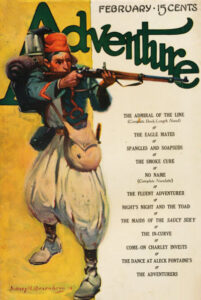

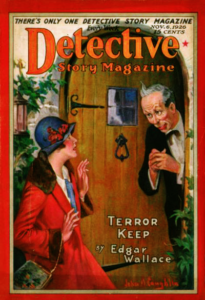

Across the pond, his work was increasingly found in Adventure, Argosy All-Story Weekly, Collier’s, Everybody’s Magazine, New Story Magazine, The Popular Magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, Short Stories, and other American magazines. In later years came Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine, Dime Mystery Book Magazine, Flynn’s (which later became Detective Fiction Weekly), The Illustrated Detective Magazine, Jungle Stories, and other pulps. His stories were also featured in all but one issue of Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine, a British digest that ran for 37 issues during the middle to late sixties.

Across the pond, his work was increasingly found in Adventure, Argosy All-Story Weekly, Collier’s, Everybody’s Magazine, New Story Magazine, The Popular Magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, Short Stories, and other American magazines. In later years came Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine, Dime Mystery Book Magazine, Flynn’s (which later became Detective Fiction Weekly), The Illustrated Detective Magazine, Jungle Stories, and other pulps. His stories were also featured in all but one issue of Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine, a British digest that ran for 37 issues during the middle to late sixties.

Wallace’s stories about Colonial Africa and the British Army were one thing. But it was “thrillers” that were his true vocation. Wallace labeled them, “pirate stories in modern dress.” As Michael Mallory suggested in Mystery Scene #130 (Summer 2013):

“The fictional world of Edgar Wallace is populated with colorfully named criminal organizations — the “Fellowship of the Frog,” the “Red Hand,” and the “Crimson Circle,” to name a few — supervillains, outwardly respectable men with secret lives, intrepid young amateur sleuths (often reporters), plucky heroines, and assorted hoods, crooks, and gangsters. He was also one of the first to feature a policeman as the protagonist in a story, as opposed to an amateur sleuth. His narrative style is at once breathless, conversational, and melodramatic, while he frequently confides in the reader.”

In 1921, Wallace signed with Hodder and Stoughton, a British publishing house that agreed to publish everything he wrote as fast as he could write it. “Chain-smoking cigarettes and gulping down cup after cup of sweet, strong tea, Wallace dictated his novels onto wax cylinders or directly to a typist. Working in a whirling fury of creativity he’d sometimes complete an entire book in 72-hours.”

Wallace introduced his most memorable character, Mr. J. G. Reeder, in his 1924 novel Room 13. Working for the Public Prosecutor, Reeder was a middle-aged, unfashionably dressed man, seemingly innocuous and timid. His outward appearance masked a keen intellect that could decipher the most convoluted schemes. “I see wrong in everything,” he suggests in The Mind of J.G. Reeder. “That is my perversion—I have a criminal mind!”

Wallace introduced his most memorable character, Mr. J. G. Reeder, in his 1924 novel Room 13. Working for the Public Prosecutor, Reeder was a middle-aged, unfashionably dressed man, seemingly innocuous and timid. His outward appearance masked a keen intellect that could decipher the most convoluted schemes. “I see wrong in everything,” he suggests in The Mind of J.G. Reeder. “That is my perversion—I have a criminal mind!”

Other series characters produced by the “King of Thrillers” included The Just Men, Inspector Elk of Scotland Yard, the vigilante and master of disguise Henry “The Ringer” Milton, and Four Square Jane, a female Robin Hood.

His books sold by the thousands and were translated into more than twenty languages. As early as 1916, his work was also adapted into films such as The Man Who Bought London, The Green Terror, The River of Stars, and The Four Just Men. He also began to write for the film industry himself, beginning with Nurse and Martyr, the story of a British nurse during World War I.

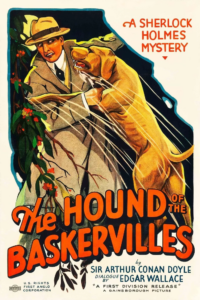

One of the most widely read authors in the world during the first third of the twentieth century, Edgar Wallace wrote over 170 novels, nearly a thousand short stories, 25 stage plays, many film scripts, historical non-fiction, ballads, and poetry. This was on top of his journalism, criticism, newspaper columns, sports reporting, and publishing. At least 160 films — as well as radio and television presentations — were adapted from his work, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, produced in England from Wallace’s screenplay in 1932.

One of the most widely read authors in the world during the first third of the twentieth century, Edgar Wallace wrote over 170 novels, nearly a thousand short stories, 25 stage plays, many film scripts, historical non-fiction, ballads, and poetry. This was on top of his journalism, criticism, newspaper columns, sports reporting, and publishing. At least 160 films — as well as radio and television presentations — were adapted from his work, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, produced in England from Wallace’s screenplay in 1932.

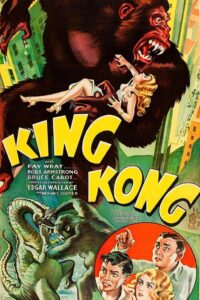

Despite his tremendous success, Wallace was constantly teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. He lived extravagantly and gambled extensively. He even owned several racehorses. Seeking additional income and perhaps hoping to escape his creditors, Wallace was lured to Hollywood in 1931. There he became a highly paid script doctor for RKO Pictures. Later that same year, he was asked to help on Merian C. Cooper’s “gorilla picture.” Wallace penned a 110-page script, the first draft for a film that was eventually titled King Kong.

Unfortunately, Wallace would not live to see the film. In My Hollywood Diary — published in 1932 by Hutchinson & Co. — the celebrated author wrote:

Unfortunately, Wallace would not live to see the film. In My Hollywood Diary — published in 1932 by Hutchinson & Co. — the celebrated author wrote:

“Cooper called me up last night and told me that everybody who had read ‘Kong’ was enthusiastic. They say it is the best adventure story that has ever been written for the screen.”

Suffering from undiagnosed diabetes, Wallace lapsed into a coma — probably after suffering a stroke — and died at the age of 56 on February 10, 1932.

Again, Michael Mallory:

“How is it that a writer once considered to be second in popularity only to Dickens, whose face once adorned the cover of Time magazine, became a memory so quickly after his death? Possibly because Wallace’s output was so enormous that it was hard for any one work, even any one series, to achieve classic status. Also, unlike his contemporaries Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, he never created a truly iconic character. It was the name Edgar Wallace that sold the books, not a particular title or character, and once the real Edgar Wallace was gone, his readers moved on and his works fell out of print.”

Incredibly prolific, it has been estimated that more than 50 million copies of Wallace’s books sold during his lifetime. During the twenties, his publisher claimed that one of every four books sold in England was by Edgar Wallace. By 1990, the head of the Edgar Wallace Society estimated that sales of the author’s work had exceeded 200 million.

Incredibly prolific, it has been estimated that more than 50 million copies of Wallace’s books sold during his lifetime. During the twenties, his publisher claimed that one of every four books sold in England was by Edgar Wallace. By 1990, the head of the Edgar Wallace Society estimated that sales of the author’s work had exceeded 200 million.

The “King of Thrillers” was truly a “Master of Blood and Thunder.”

For more on Edgar Wallace and his work, please visit our YouTube Channel.

And while you’re there, be sure to subscribe.

Our lead image is the cover for the April 15, 1929 issue of Time, with Edgar Wallace pictured on the front cover.

New-Story Magazine for March 1915, with cover by Harvey T. Dunn, illustrating Edgar Wallace’s “The Four Just Men,” reprinted in its entirety. Wallace’s novel was originally self-published in 1905 by The Tallis Press.

The first American edition of Edgar Wallace’s Sanders of the River, published in 1930 by Doubleday, Doran in New York. The dust jacket art is by Bernhard Stafford Good. The artist was born in England and moved to the United States, actively painting in Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New York. He painted at least one pulp cover, the October 20, 1925 issue of Adventure.

The February 1915 number of Adventure — with cover by Sidney Riesenberg — features the Edgar Wallace story, “The Fluent Adventurer,” as well as stories by Stephen Chalmers, Octavus Roy Cohen, Talbot Mundy, and others.

Edgar Wallace’s novel, “Terror Keep” — featuring Mr. J. G. Reeder — was serialized in five parts by Detective Story Magazine. It began in the November 6, 1926 number, with front cover art by John A. Coughlin.

Edgar Wallace wrote the screenplay for the 1932 adaption of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, a British mystery film directed by Gareth Gundrey and starring John Stuart, Robert Rendel, and Frederick Lloyd. The first sound version of Doyle’s classic novel, it was made by Gainsborough Pictures. The film poster is by an unknown artist.

Edgar Wallace wrote the first draft script for RKO Pictures 1933 film King Kong, produced and directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, with special effects by Willis H. O’Brien. Included in Wallace’s 110-page script was the climactic Empire State Building scene. The film poster is by an unknown artist.

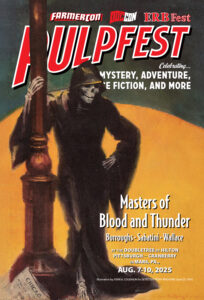

PulpFest advertising director William Lampkin adapted John A. Coughlin’s cover for the April 25, 1931 issue of Detective Story Magazine, illustrating the Edgar Wallace serial, “On the Spot.” Edgar Wallace adapted the Chicago gangster novel from his popular stage play of the same name.

Finally, our featured image is excerpted from John A. Coughlin’s cover for the June 27, 1931 number of Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine.

Detective fiction fan Pete Collins joined our staff in September 2024. That month, he contributed an overview of Detective Fiction Weekly to salute the magazine’s centennial. We look forward to Pete’s future contributions to our website.