On May 8, 1874 — 150 years ago — Joseph Thompson Shaw was born to Milton and Nellie Shaw in Gorham, Maine. A lover of books and the outdoors, Joe Shaw was educated in Gorham, and later, Bowdoin College, a private liberal arts college in Brunswick Maine.

On May 8, 1874 — 150 years ago — Joseph Thompson Shaw was born to Milton and Nellie Shaw in Gorham, Maine. A lover of books and the outdoors, Joe Shaw was educated in Gorham, and later, Bowdoin College, a private liberal arts college in Brunswick Maine.

A member of the editorial board for the Bowdoin Orient — the college newspaper — Shaw also took up fencing during his four-year stint at the college. In 1910, he won the first of four national fencing titles and was known as “one of the best fencers in America, especially with the saber.”

With Europe engulfed in war, Joseph Shaw began training US soldiers and draftees in the use of the bayonet as a fighting weapon. In 1918, he volunteered for service with the United States Army and was commissioned a captain. After the signing of the armistice to end the First World War, Shaw was reassigned to the American Relief Administration under Herbert Hoover. He was named the Director of the Bureau of Children’s Relief in the newly created country of Czechoslovakia. Working in the former territory of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Shaw’s tenure was marked by a sense of righteousness and fair play.

Although he remained in Czechoslovakia through 1924, the Children’s Relief Program was demobilized in September 1919. Little is known about this period of Shaw’s life except that he “turned seriously to writing” during his time in Central Europe.

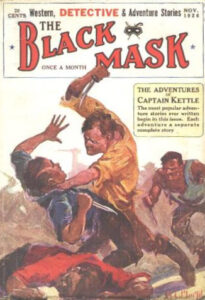

Having returned to the United States in 1924, Shaw settled near New York City. In 1926, he approached Phil Cody, editor of The Black Mask, with a story. Recently promoted to vice president of Pro-Distributors Publishing Company and Circulation Director, Cody hired Shaw as his replacement. Beginning with its November 1926 issue, Joseph T. Shaw became the editor of The Black Mask.

Having returned to the United States in 1924, Shaw settled near New York City. In 1926, he approached Phil Cody, editor of The Black Mask, with a story. Recently promoted to vice president of Pro-Distributors Publishing Company and Circulation Director, Cody hired Shaw as his replacement. Beginning with its November 1926 issue, Joseph T. Shaw became the editor of The Black Mask.

When Shaw took over at Black Mask — he dropped “The” from the magazine’s title following the April 1927 issue — a good deal of the groundwork establishing the hardboiled school of detective fiction writing had been performed by his predecessors.

George Sutton and his assistant Harry North had taken on Carroll John Daly and Dashiell Hammett in late 1922 and Erle Stanley Gardner in late 1923. Phil Cody — who succeeded Sutton in early 1924 — added Tom Curry, Nels Leroy Jorgensen, Frederick Nebel, and Raoul Whitfield to the mix in 1925 – 26.

During Sutton’s and Cody’s tenure, The Black Mask was largely an action title, publishing a mix of western, detective, and adventure fiction. It would retain this focus well into Joe Shaw’s reign as editor, only concentrating on detective fiction in mid-1933.

Upon assuming the editorship of the Pro-Distributors pulp magazine, Joe Shaw endeavored to make Black Mask “the only magazine of its kind in the fiction world of today and the future.” He found detective fiction to be “the most absorbing of all literature” and asked his writers to create stories that were . . .

. . . real in motive, character, and action. They must be plausible and not absurd. They must be clear and understandable and not confused. In a word, they must be written with the keenest thought and greatest skill. . . . All stories submitted to Black Mask are judged and selected with these cardinal requirements in mind, together with the necessity for swift movement in starting and in the development of plot. . . . detective fiction as we view it has only commenced to be developed. As a matter of fact, we expect the greatest and most noteworthy development in this particular field of literature than will be seen in any other.

Our policy then, calls for the best stories obtainable. . . . stories that grip, interest, thrill; with characters that one can feel exist; characters with motives and engaging in action logically born of those motives. Both motive and action to be so realistic as to insult the intelligence of none; to seem, not only possible, but inevitable.

Fiercely loyal to his magazine’s ideals and the writers whose work embodied them, Shaw tirelessly promoted Black Mask and praised the talents and accomplishments of his authors, even after they had moved on to better-paying markets. Little wonder then that during his early tenure as the magazine’s editor, the monthly circulation of Black Mask grew from 66,000 to 130,000, despite the growing effects of The Great Depression.

Fiercely loyal to his magazine’s ideals and the writers whose work embodied them, Shaw tirelessly promoted Black Mask and praised the talents and accomplishments of his authors, even after they had moved on to better-paying markets. Little wonder then that during his early tenure as the magazine’s editor, the monthly circulation of Black Mask grew from 66,000 to 130,000, despite the growing effects of The Great Depression.

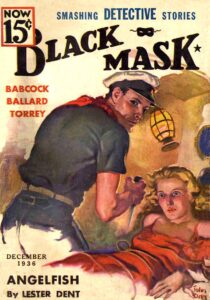

Unfortunately, as the hard times of the 1930s progressed, Black Mask lost readers as it competed for market share with pulps that could be had for a dime. Rather than change his magazine’s slant, Joe Shaw resigned as editor of Black Mask at the end of August 1936. He had recently purchased Lester Dent’s two Oscar Sail stories, considered by many to be the best work done by the writer of the popular Doc Savage series. Having appreciated Shaw’s tempered guidance, Dent never submitted another story to the magazine. He later remarked:

“When you went into his office and talked with Shaw, you had feelings of stature, you felt you were doing fiction that was powerful. Cap gave this strength to his writers. . . . when you did something lean and powerful, no excess wordage anywhere, then you had Black Mask style.”

Leaving behind enough material to keep Black Mask running through the end of 1936, Shaw joined a literary agency. For the remainder of his life, he worked in the field, representing a variety of authors over his remaining years.

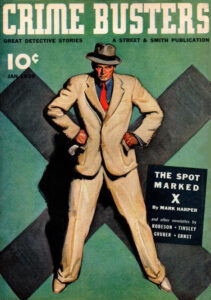

Shaw also began freelancing in 1938. Using the nom de plume of Mark Harper, he contributed the Cass Manning series to Street & Smith’s Crime Busters and Street & Smith’s Mystery Magazine. As Harper, he also sold stories to All Star Detective, Black Mask, Clues, Detective Short Stories, Detective Story Magazine, Dime Detective, Doc Savage, and The Shadow.

Shaw also began freelancing in 1938. Using the nom de plume of Mark Harper, he contributed the Cass Manning series to Street & Smith’s Crime Busters and Street & Smith’s Mystery Magazine. As Harper, he also sold stories to All Star Detective, Black Mask, Clues, Detective Short Stories, Detective Story Magazine, Dime Detective, Doc Savage, and The Shadow.

Commenting on Shaw’s 1940 story, “The Rolling Heads,” Street & Smith editor John Nanovic remarked, “Harper’s strongest point, in my opinion, is the quiet restraint which he puts into his best work.” As Harper, Joseph T. Shaw contributed nearly forty stories to the rough-paper market.

In 1945, Shaw approached Simon and Schuster with the idea of an anthology featuring the best of the Black Mask stories by the leading contributors to the Hard-Boiled School of Mystery Writing. The Hard-boiled Omnibus: Early Stories from Black Mask was first published in 1946 and included fifteen stories originally published in Black Mask.

Five years later, Shaw followed with Spurs West!, published by Perma Books in 1951. It featured eleven of the best western stories published between 1935 and 1950, with work by Frank Bonham, A. B. Guthrie, Ernest Haycox, and others.

In 1951, Joe Shaw opened his own literary agency, a month shy of his seventy-seventh birthday. He continued at the company’s helm, representing such authors as William R. Cox, Norman A. Fox, Tommy Thompson, and Thomas Walsh.

Joseph Thompson “Cap” Shaw died on August 1, 1952 while working at his agency in New York City. In a letter to Mike Tilden, Managing Editor of Popular Publications, Tommy Thompson wrote:

He was a damn sight more than an editor — he was a pillar of strength, a whipping boy who never whimpered and a guy who would stroke your head by mail. We’re going to miss him, and I know a lot of editors are, but as I just wrote Norman Fox, a select few of us will always have a little claim to fame: “We were one of Cap Shaw’s boys.”

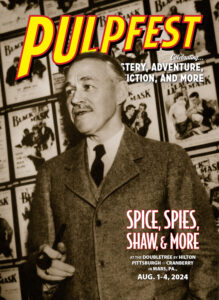

At PulpFest 2024, we’ll salute the 150th anniversary of the birth of Joseph Thompson “Cap” Shaw, the legendary editor of Black Mask. We’ll have presentations on the early years of the magazine and the later “Popular” years of the pulp. We’ll also have an interview with Peter Wolson, the son of Peter Paige, a former Black Mask writer. It’s all part of our celebration of “Spice, Spies, Shaw, and More” at PulpFest 2024.

Our featured image is excerpted from John Drew’s cover art for the December 1935 Black Mask. Drew also painted the cover art for the December 1936 Black Mask, illustrating Lester Dent’s Oscar Sail story, “Angelfish.” A freelance artist, Drew painted covers for a wide range of magazines including Clues Detective, Everybody’s Magazine, Ranch Romances, Sea Stories, Terror Tales, and Western Story Magazine.

Our lead image was adapted by PulpFest advertising director William Lampkin from the dust jacket for the late Milton Shaw’s 2019 biography of his father, Joseph T. Shaw: The Man Behind Black Mask, published by Steeger Books. It’s a photograph of Shaw at the Black Mask office that was taken circa the early to mid-1930s.

is excerpted from a 1923 photograph of Joseph T. Shaw at the Waccabuc Country Club, Westchester County, New York. He was 48-years-old at the time.

Joseph T. Shaw became the editor of The Black Mask with its November 1926 issue. H. C. Murphy was the cover artist. He painted many covers for the pulps during the 1920s, including the September 1929 issue of Black Mask which featured the opening segment of Dashiell Hammett’s five-part serial, “The Maltese Falcon.”

Graves Gladney most likely painted the cover art for the January 1939 issue of Crime Busters, illustrating the Mark Harper story, “The Spot Marked X.” Joe Shaw wrote eleven Cass Manning stories for the magazine and its companion, Street & Smith’s Mystery Magazine.

For more on Joseph Thompson Shaw, please visit our YouTube Channel for Craig McDonald’s latest video, Joseph “Cap” Shaw & His “Black Mask Boys.”

And while you’re there, please be sure to subscribe.