Pulp magazines have influenced writers, artists, film directors, software developers, and countless others over the years. Our “PulpFest History” articles focus on the rough-paper writers, editors, publishers, and artists who have inspired and continue to inspire the creators of the world’s popular culture.

History tends to regard Raoul Whitfield as a hardboiled, Dashiell Hammett wannabee and also-ran.

History tends to regard Raoul Whitfield as a hardboiled, Dashiell Hammett wannabee and also-ran.

Raoul Whitfield was assuredly a certified “Black Mask Boy.” He was also handsome and charismatic enough to allegedly score a screen test, or two. Hard evidence in support is lacking, but some claim Whitfield was indeed a limited silent film bit actor.

Admittedly, Whitfield was also a Hammett acolyte, eventual friend, a staunch advocate for the much less prolific “Dash,” and a stalwart Hammett drinking partner.

Like Hammett, Whitfield was also a World War I-era veteran, and — again, the evidence is scant but the little there is, is compelling — an Air Ace in the skies over France.

Indeed, Whitfield’s prowess in a plane is something that typifies not just his murky biography, but his pulp bibliography, as well.

And, just possibly, Raoul Whitfield was a successful wife killer. (More on that, to come.)

These days, Whitfield’s increasingly ebbing fame isn’t helped by his comparatively brief, if wildly prolific stint publishing for a string of pulp magazines under his birth name, as well as the florid pseudonyms of “Ramon Decolta” and “Temple Field.”

If he remains less known than Hammett, Whitfield’s bibliography is infinitely more robust than that of Sam Spade’s and Nick Charles’ creator.

If he remains less known than Hammett, Whitfield’s bibliography is infinitely more robust than that of Sam Spade’s and Nick Charles’ creator.

Making the leap in 1930 to hardcover novelist, Whitfield attempted what Raymond Chandler, Hammett, and other pulp novelists would also do once they caught the attention of New York hardcover publishers and were required to produce novel-length works.

Whitfield took several of his short stories already commercially proven in the pulps and attempted to meld them into a larger, but ultimately uneven unified storyline.

Whitfield’s first such “novel” was titled Green Ice. Set in 1930s industrial Pittsburgh, it depicts a place now far removed from the present host city for PulpFest: “Red flames streaked up into the sky from the plant stacks. Red smoke hung low. The air was heavy, thick with grime.”

Hammett declared in a blurb for Green Ice, “The plot does not matter. What matters is that here are 280 pages of naked action pounded into tough compactness by staccato, hammerlike writing.”

In the space of a few years, Whitfield published several hardcover crime novels under his own and a pen name, as well as a series of juvenile-reader collections for Knopf in hardcover. The latter were built around aeronautics, naval adventures, and circus life.

Soon after this flurry of Depression-era books and short stories, Whitfield largely disappeared from the publishing world.

In just a very few years, he was dead.

***

Like his pen names, Whitfield’s backstory is somewhat exotic.

Born in New York on November 22, 1896, Raoul Falconia Whitfield (in later official documents, he mysteriously reported his middle name as “Fauconnier”, suggesting “falconer”), traveled Asia with his father.

He grew up in the Philippines, providing settings and experiences that figured in many stories about Filipino detective Jo Gar. Two-dozen Gar stories would appear in Black Mask between 1930 and 1933. They were published under the Ramon Decolta pseudonym.

Whitfield’s knowledge of Manila is evident from his descriptions in the Gar stories:

“The caleso, pulled by a sturdy horse, moved swiftly toward the Bay. It was a dark night; there was no moon. A hot breeze blew in from the direction of the Cavite. The Luneta, flanked by the Manila Hotel and the Army and Navy Club, was behind now.”

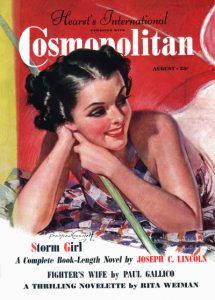

The final Jo Gar story, “The Great Black,” printed in the August 1937 edition of Cosmopolitan, is also the last work known to be published by Whitfield in his lifetime. Most critics and readers regard the Gar stories as representing Whitfield’s high-water mark as a fiction writer. Other lesser Whitfield characters include Mel Ourney, Gerry Kells, Donald Free, Buck Kent, and Ben Jardinn.

***

The first fiction publication for Whitfield came in 1924, in Street and Smith’s Sports Stories. More followed in Breezy and Droll Stories.

In 1926, in addition to publishing in an increasing number of other pulps including Battle Stories and Adventure, Whitfield sold eight short stories to Black Mask, starting with “Scotty Troubles Trouble.” It was published in the March 1926 issue of the magazine.

In less than a decade, Whitfield placed nearly 100 stories with Black Mask, wildly dwarfing the output of Hammett, Chandler, or virtually any other contributor to the venerable crime pulp. Some Black Mask covers even herald stories by both Raoul Whitfield and Ramon Decolta.

Unfortunately, Whitfield was never a prideful craftsman, nor a consistent prose stylist. He was a kind of writing machine when he sat down at the typewriter.

At his best, he tended to effectively cut to the chase, as in his telegraphic description of a newspaper account of a slaying:

“‘Angel’ Cherulli had been found in an alley behind his club, with a flock of thirty-eights in his stomach and chest. There wasn’t a clue. He had many enemies. The rest of the story was just writing.”

Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine founder Frederic Dannay described Whitfield’s own writing routines as recounted by the author’s first wife:

“Raoul Whitfield always wrote very easily and quickly, and with a minimum of correction. He had a particular talent for starting with a title and writing around it. His wife has said that once he had a title, he had the story. He would place neat stacks of chocolate bars (which he ate by the thousands) to the right of his typewriter, and a picket fence of cigarettes to his left. He wrote and chain-smoked and ate, all in one unified operation. He could be surrounded by a cocktail party going at full blast — and keep right on writing.”

Apropos of cocktail parties and the high life, Whitfield did earn a major fan among the Jazz Age literati: F. Scott Fitzgerald insisted to a critic/author friend Whitfield was “as good as Hammett.” Fitzgerald, some scholars and biographers believe, also bedded a Whitfield wife; that same wife would also make a run at novelist Thomas Wolfe.

***

After leaving his wife, Raoul Whitfield drifted to Los Angeles.

There, he undertook screenwriting, including an adaptation of one of his short stories, as well as reported script work on The Mask of Fu Manchu, starring Boris Karloff.

Whether Raoul recognized it or not, his best years as a writer were behind him.

Whether Raoul recognized it or not, his best years as a writer were behind him.

The ink hardly dry on either’s divorce papers, Whitfield wed the previously twice-married Emily Davies Vanderbilt Thayer.

Accounts indicate Whitfield, always an energetic elbow-bender, was losing a long and escalating battle against alcoholism, much like the same wet-brain spiral that would truncate Hammett’s writing career.

In a dust jacket description for Raoul’s doppelganger “Temple Field,” it was asserted around the same time, “Temple Field lives in New York City, likes to collect material in night outlets and speakeasies, and is young enough to enjoy writing every word he writes.”

But the once-prolific Whitfield/Field was, in reality, winding down as a writer, no longer the uncanny word-machine he was when, for a time, he ranked as possibly the highest-paid pulp magazine scribe in his field.

Raoul Whitfield died on January 24, 1945, at the age of 48. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

***

The most recent attention paid to Raoul Whitfield came in 2020, in an article on Whitfield that I penned for The Pulpster #29, a special, extra-length edition of the magazine published during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. The article was focused on Whitfield’s rather sordid personal history and two particular marriages, both of which ended in his wives’ “suicides.”

Those quotation marks around “suicides?”

In at least one case, there is some reasonable suspicion to make the case Whitfield murdered at least one of his three wives, and did so successfully, aided in large part by his aviation skills. The idea inspired a novel about Whitfield written by the late Walter Satterthwait. Entitled Dead Horse, it was published in 2006.

You can read more about that theory, and Satterthwait’s fine novel in The Pulpster #29, available for order here.

***

Earlier this year, a very fine collection of previously uncollected but linked short stories by Whitfield, gathered under the title Laughing Death, was published by Steeger Books in hardbound and softcover formats; it features a new introduction by James Reasoner.

As described by Steeger Books, “Laughing Death is a story of gunfire and airships, of love and revenge. Sanford Greer (S.G.) Prosecuting Attorney of Center city, is put ‘on the spot’ by five men. Gary Greer, who is the pilot in charge of the South Side Airport, starts out to get those five men and avenge his father’s death.”

The Steeger Books blurb favorably compares the linked stories to “the gusto of an Edgar Wallace,” but perhaps more piercingly, to “something of the power of a Dashiell Hammett.”

Indeed, the Greer stories appeared in a spread of Black Mask magazine editions that included serializations of Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon and The Glass Key. It is indeed fortunate that these stories are now readily available as we celebrate the 125th anniversary of Raoul Whitfield’s birth.

Along with Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, Raoul Whitfield is considered one of the leading writers from editor Joe Shaw’s Black Mask school of writers. In less than a decade, Whitfield placed nearly 100 stories with Black Mask.

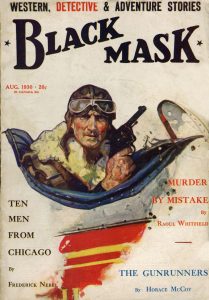

Aviation, and Whitfield’s passion for flying, inform much of his fictional work, such as “Murder by Mistake,” published in the August 1930 Black Mask.

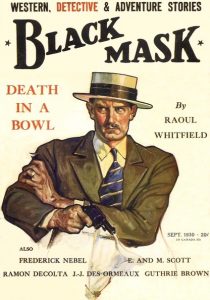

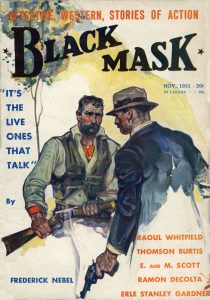

Outside of pulp fiction circles, Raoul Whitfield is primarily remembered today for two novels — Green Ice and Death in a Bowl. The latter was originally serialized in three consecutive issues of Black Mask, beginning with the September 1930 number. It introduced readers to Hollywood detective Ben Jardinn. The issue also featured a Jo Gar story, one of several instances when Whitfield shared cover credit with one of his pen names. Another instance was the November 1931 Black Mask. Unfortunately, a reader buying the pulp for the Decolta yarn would have been disappointed. The author does not appear in the issue.

The Steeger Books collection, Laughing Death, features cover art by J. W. Schlaikjer. The illustration originally appeared on the October 1929 number of Black Mask. Schlaikjer also contributed the cover art for the three issues of Black Mask featured in our post.

Bradshaw Crandell painted the cover for the August 1937 Cosmopolitan. Whitfield’s final Jo Gar story is featured in the issue.

The author of the Edgar-nominated Hector Lassiter historical crime series, Craig McDonald is an award-winning novelist, journalist, and editor. His series chronicles the exploits of a fictional Black Mask author and his encounters with such notable figures as Ernest Hemingway, Orson Welles, Ian Fleming, and Lester Dent. In addition to his Edgar nomination, Craig was also a finalist for the Anthony, Gumshoe, and Crimespree Magazine Award for best first novel.