Stories of intrigue have existed since mankind first set quill to papyrus. The Old Testament abounds with tales of spies and their doings. Espionage can likewise be found in the epics of the Greeks, Romans, and other societies.

Stories of intrigue have existed since mankind first set quill to papyrus. The Old Testament abounds with tales of spies and their doings. Espionage can likewise be found in the epics of the Greeks, Romans, and other societies.

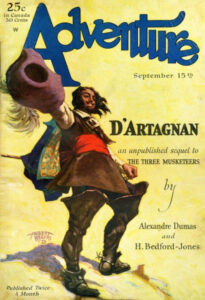

In 1821, James Fenimore Cooper published the first American espionage novel — The Spy. Cardinal Richelieu employs “Milady” as a spy in Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers. Rudyard Kipling’s Kim tells of an Englishman — raised as a native of India — who must choose between the mysticism of the East and his service to the crown as an agent of the British Secret Service.

Given all the appearances of undercover agents throughout literature, most scholars trace the roots of the modern espionage novel to Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands, first published in 1903. At the same time, Childers’ novel serves as an example of the sub-genre of science fiction known as the imaginary or future war story. Written during a time when many citizens of the British Isles harbored a real concern that such an event was likely to occur, The Riddle of the Sands concerns two British yachtsmen who uncover a German plan to invade England.

The second half of the Nineteenth Century saw a dramatic shift in power on the European continent. France had been the power to fear in the early years of the century. Even following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, the French had managed to remain the dominant state on the mainland. This changed when France suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Great Britain looked upon Germany’s rising fortunes under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck with growing alarm.

Such was the backdrop to the publication of The Riddle of the Sands, the earliest of many British espionage novels. Others among their numbers are John Buchan’s Richard Hannay stories, the thrillers of E. Phillips Oppenheim, the works of Eric Ambler, and later, Graham Greene, continuing into Ian Fleming’s James Bond adventures and the novels of John leCarré. Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes even dabbles in the cloak-and-dagger world in such stories as “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans” and His Last Bow.

It was within the cauldron of the Great Depression and the rise of fascism on the European continent that Popular Publications’ Secret Service Operator #5 was born. According to Popular publisher Henry Steeger:

It was within the cauldron of the Great Depression and the rise of fascism on the European continent that Popular Publications’ Secret Service Operator #5 was born. According to Popular publisher Henry Steeger:

“I was very anxious at that time to say something about the depression and the political elements of the world and, by this time, the trend of story-telling had begun to assume a broader canvas. In other words, instead of talking about individuals, we began talking about nations and armies, etc. Operator #5 was planned deliberately to exert more influence in this direction than The Spider.”

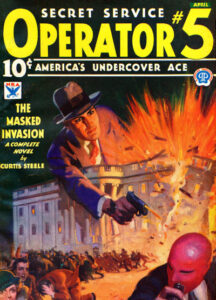

The Secret Sentinel column in the first issue of Secret Service Operator #5 — dated April 1934 — mirrors Steeger’s concerns:

Perhaps at no other time in history has the world been in greater danger of flaming suddenly into war — a holocaust which, according to one authority, would make the so-called World War look “as tame and gentle as a Sunday School picnic.”

With the acknowledged breakdown in the economic machinery of every nation, a wave of intense nationalism — evidenced by such aggressive forms of government as the Nazi rule of Germany, Communism in Russia, and Fascism in Italy — has swept the civilized world. Economic barriers are heightened; disarmament agreements are almost openly scrapped; munition plants, navy yards, and airplane factories are booming.

But one phase of this national uneasiness is carried on secretly. It is by far the most thrilling, the most dangerous, and from a military standpoint, one of the most valuable. Espionage!

For example: for the second time within a period of months, commercial espionage has been discovered in the U.S.S.R.; in France, certain men and women have been arrested for the possession of important military information; in Germany, a foreigner was recently executed for setting fire to the Reichstag buildings.

Our defense against this secret legion working against us is placed in the hands of a few picked men of the Intelligence Department. Men such as Jimmy Christopher, known as Operator #5 . . . . Follow him as he wages a one-man war against the foreign agents who are plotting America’s ultimate destruction.

Frederick C. Davis — who authored the first twenty Jimmy Christopher adventures under the Curtis Steele house name — recalled in 1969 that “The basic concept of Operator 5 came from Harry Steeger, the publisher, or Rogers Terrill, the editor, or both. It was that Operator 5 must save the United States from total destruction in every story, every month. When I was called in to start the series, they already had a cover illustration — the White House being blown up. I did the first Operator 5 around this picture. The characters in detail, the ideas, the plots, and the gimmicks were all my inventions.”

Frederick C. Davis — who authored the first twenty Jimmy Christopher adventures under the Curtis Steele house name — recalled in 1969 that “The basic concept of Operator 5 came from Harry Steeger, the publisher, or Rogers Terrill, the editor, or both. It was that Operator 5 must save the United States from total destruction in every story, every month. When I was called in to start the series, they already had a cover illustration — the White House being blown up. I did the first Operator 5 around this picture. The characters in detail, the ideas, the plots, and the gimmicks were all my inventions.”

In novel after novel, the stalwart Christopher defeats one enemy after another — The Yellow Empire, the Man-Breaker, the New Populists, the Red Invaders, Montezuma the Third, the Dragon Emperor, Emperor Rudolph and the Purple Empire, Frederick Blaintree and the Brown Shirt Party . . .

The stories fairly ooze with patriotism:

The rhythmic tramp of marching feet throbbed through the streets of New York. Out of the doors of the United States’ armories troops came marching. The brilliant glare of gasoline lanterns lighted their way. Out into Fourth Avenue long lines formed. Down Lexington squads paced double-quick. The air crackled with sharp commands as heels clicked in chorus.

How’s that for something to stir the blood of a ten-year-old boy with a deep regard for his country? No wonder young boys like Wooda “Nick” Carr fell hook, line, and sinker for the adventures of Secret Service Operator #5. However, if the patriotism wasn’t enough to grab a boy as it did Carr, there were also magic tricks to do the job.

No matter how furious the action, at least once in most of the early stories, Jimmy performs some sleight-of-hand and reveals how the trick was done. How could any boy in his right mind resist Christopher’s magic, especially when it’s explained?

Finally, if the love of country and wizardry were unable to hook a kid, the character of Tim Donovan himself was on hand to convince the young reader to part with a dime. The “freckled-faced, Irish lad” — as author Davis called him — was Jimmy Christopher’s right-hand man. Operator #5 relies on the boy for surveillance, delivering messages, and even driving his specially designed Diesel-powered roadster across the country. In fact, there are times when young Tim Donovan succeeds when the agents of the Secret Service — including Jimmy — fail. In “The Masked Invasion,” for instance, it is Tim Donovan who discovers the Masked Master’s headquarters while Operator 5 and his fellow agents are following a string of clues to the wrong place.

Davis’ “Irish lad” surely enthralled a boy or two, convincing them to bring home Operator #5 from the drug store or corner newsstand where pulps were sold.

Davis’ “Irish lad” surely enthralled a boy or two, convincing them to bring home Operator #5 from the drug store or corner newsstand where pulps were sold.

. . . gripping the cord, he pushed legs over the sill. His hands went white-knuckled as his feet hung down into space. Wrapping legs about the whipping cord, he lowered himself, hand over hand. Wind whipped past him, swinging him against the sheer side of the spire. He felt the cord rubbing the sharp edge of the stone sill above. It was stretching slightly under his weight.

Tim Donovan lowered himself inch by inch into the abyss of dizzy space. He was near the window of the floor below now. When he saw the light shining on his body, he let himself down more rapidly. Quickly he glimpsed in . . .

It was all there in Secret Service Operator #5 — a strong, dedicated, clean-cut hero with a boy sidekick, thrills and fantastic adventure, espionage, danger, magic, and above everything else, the value of patriotism and devoting oneself to one’s own country and its ideals.

“I consider it a high honor, Operator 5,” said the President of the United States, “to meet you. . . . You have rendered your country a service valuable beyond all calculation. Nothing I could say would fully declare our gratitude to you for your loyal service. Your name is unknown to the nation you have served. James Christopher can never be known as the man who almost single-handedly averted the destruction of this nation. You move in secrecy. Fame cannot reward you. History will never mention you, though you deserve to be ranked among the greatest. There can be no recompense to you, except these few words of mine, this clasp of my hand, in the name of the people of the United States of America.”

Cloaks and daggers, imaginary wars, and other sleights-of-hand — the stuff of Jimmy Christopher, America’s undercover ace, Secret Service Operator #5.

Emile C. Tepperman, IV has been writing occasionally for our website since 2017. He is purportedly the great-grandson of pulp author Emile Clemens Tepperman, who is best remembered for the thirteen-part Purple Invasion series that he penned for Popular Publications’ Secret Service Operator #5. It has been called “The War and Peace of the Pulps.”

Emile C. Tepperman, IV has been writing occasionally for our website since 2017. He is purportedly the great-grandson of pulp author Emile Clemens Tepperman, who is best remembered for the thirteen-part Purple Invasion series that he penned for Popular Publications’ Secret Service Operator #5. It has been called “The War and Peace of the Pulps.”

The senior Tepperman took over the series with “Raiders of the Red Death,” published in the December 1935 issue of the Popular Publications hero pulp. He would write 19 lead novels for Secret Service Operator #5, all of them published under the Curtis Steele house name.

Following Tepperman as Curtis Steele was Wayne Rogers — also known as A. H. Bittner. Rogers/Bittner wrote the last nine published stories in the series, plus a tenth adventure entitled “Hell’s Lost Battalion.” Following the November/December 1939 issue, Popular Publications canceled the series and Rogers’ last adventure went unpublished.

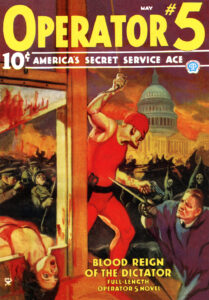

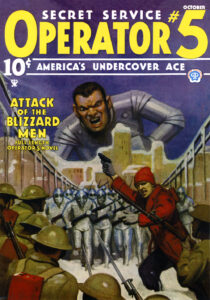

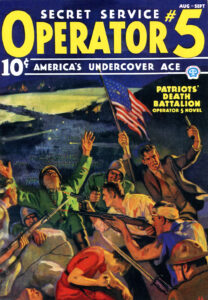

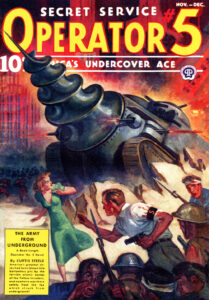

Our featured image is excerpted from John Newton Howitt’s cover art for the October 1934 issue of Operator #5. Except for the first issue, Howitt created all of the cover paintings for Popular Publications’ Operator #5 pulp, including the May 1935, October 1935, August/September 1936, and November/December 1939 issues pictured above. Jerome Rozen provided the cover art for the first issue, dated April 1934.

Our featured image is excerpted from John Newton Howitt’s cover art for the October 1934 issue of Operator #5. Except for the first issue, Howitt created all of the cover paintings for Popular Publications’ Operator #5 pulp, including the May 1935, October 1935, August/September 1936, and November/December 1939 issues pictured above. Jerome Rozen provided the cover art for the first issue, dated April 1934.

Our lead image is the September 15, 1928 number of Adventure, featuring H. Bedford-Jones sequel to The Three Musketeers. The cover art is by Hubert Rogers.

To learn more about Operator #5, visit our YouTube Channel for Craig McDonald’s latest segment on The Great Pulp Heroes . . .

And don’t forget to subscribe.