On Thursday, March 30, the cry of “Play ball” will resound across the United States. It will be the first time since 1968 that every Major League Baseball team will play its first regular season game on opening day. So there’s no better occasion than now to salute the first sports fiction pulp magazine.

On Thursday, March 30, the cry of “Play ball” will resound across the United States. It will be the first time since 1968 that every Major League Baseball team will play its first regular season game on opening day. So there’s no better occasion than now to salute the first sports fiction pulp magazine.

Sport Story Magazine debuted in August 1923, with its first issue dated September 8. Selling for 15¢, the general interest sports pulp featured stories and articles about baseball, basketball, boxing, football, hockey, horse racing, polo, rowing, skiing, tennis, track, wrestling, and just about every other sport under the sun.

Sports fiction wasn’t born in 1923. Millennia ago, prehistoric artists were telling hunting stories on cave walls. Homer featured sporting events in The Illiad, written around the late 8th century BC. The Bible describes a knock-down-drag-out fight between David and Goliath. Sir Thomas Malory’s knights compete in a jousting tournament in the story of King Arthur. Robin Hood wins the big archery contest and Lew Wallace’s Ben Hur triumphs over all in the chariot race.

Regardless of what came before or after, it’s probably Thomas Hughes’ 1857 novel, Tom Brown’s Schooldays, that served as the template for the many sports yarns that followed, particularly those of the Frank Merriwell school of popular fiction.

“Frank Merriwell,” or “First Days at Fardale” appeared in the first number of Tip Top Library, dated April 18, 1896. It was priced at five cents a copy and sold out. Before a year was out, Tip Top Library was rechristened Tip Top Weekly. The nickel weekly maintained a circulation of 135,000 copies for years, with an estimated 400,000 readers enjoying each weekly issue. By some estimates, its publisher, Street and Smith, released over 500 million copies of Merriwell-related publications over the years.

Merriwell’s longtime scribe, William George Patten, was born in 1866. From an early age, he wanted to be a writer. While still in his teens, he sold two short stories to Beadle & Adams and demonstrated his possibilities. In 1886, his first novel, “The Diamond Sport” or, “The Double Face of Bedrock,” found its way into Beadle’s Half-Dime Library and brought home fifty dollars. Before long, readers of the Half-Dime Library were eating up tales about Captain Claw, Daisy Dare, and Wild Vulcan — the Lone Range Rider.

Following a salary dispute with Beadle & Adams, Patten turned to other publishers including Norman Munro — publisher of the Old Cap Collier Library — and Street & Smith. The latter was looking to start a new series and made Patten an offer in a letter dated December 16, 1895:

The essential idea of this series is to interest young readers in the career of a young man at a boarding school . . . The stories should . . . be American and thoroughly up to date. Our idea is to issue, say, twelve stories . . . all dealing with life at the academy. By this time the readers will have become sufficiently well-acquainted with the hero . . . he should come into a considerable amount of money at this period . . . (so he) leaves the academy.

The essential idea of this series is to interest young readers in the career of a young man at a boarding school . . . The stories should . . . be American and thoroughly up to date. Our idea is to issue, say, twelve stories . . . all dealing with life at the academy. By this time the readers will have become sufficiently well-acquainted with the hero . . . he should come into a considerable amount of money at this period . . . (so he) leaves the academy.

When the hero is once projected on his travels there is an infinite variety of incidents to choose from. . . . After we run through twenty or thirty numbers of this, we would bring the hero back and have him go to college — say, Yale University; thence we could take him on his travels again to the South Seas or anywhere.

We believe you can give us what we require, and would be pleased to have you write us one of these stories at once.

Now calling himself Gilbert Patten, the author was offered $50 a week with no royalties. He was to deliver a weekly 20,000-word story for three years. Married with a young son and aging parents to care for, and still yearning to write the great American novel, the 29-year-old writer jumped at the chance.

He christened his hero Frank Merriwell, explaining, “The given name of Frank was taken to express one of the hero’s characteristics — open, on the level, aboveboard, frank. Merriwell was formed by a combination of two words: ‘merry’ — expressive of a jolly, high-spirited nature — and ‘well’ — suggesting abounding physical health.”

But what of Merriwell’s creator? He would become known and revered as “Burt L. Standish.”

Although Frank Merriwell was “a whiz at boxing, baseball (his ‘double shoot,’ which curved in both directions, was always good in the clutch), football, hockey, lacrosse, crew, track, shooting, bicycle racing, billiards, golf — in fact, any sport he deigned to play,” his saga also explored other genres, including mystery, adventure, romance, the outdoors, and even business tales and railroad yarns.

Although Frank Merriwell was “a whiz at boxing, baseball (his ‘double shoot,’ which curved in both directions, was always good in the clutch), football, hockey, lacrosse, crew, track, shooting, bicycle racing, billiards, golf — in fact, any sport he deigned to play,” his saga also explored other genres, including mystery, adventure, romance, the outdoors, and even business tales and railroad yarns.

When the first pulps debuted — beginning with Frank A. Munsey’s The Argosy in late 1896 — they took a similar tack, and published a range of fiction that appealed to both men and women, the young and the old.

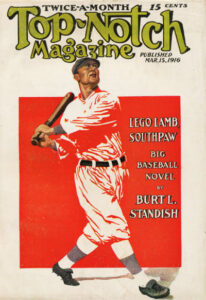

Street & Smith entered the pulp magazine field in late 1903 with The Popular Magazine. Like Argosy, the magazine featured a variety of tales, including sports fiction. During the fall of 1910, the publisher would build on its success with Popular when it converted Top-Notch Magazine to the pulp format. With the magazine’s editor hidden behind the Burt L. Standish name, it’s not surprising that the early Top-Notch would be a showcase for sports fiction and the other genres explored in Popular and the Merriwell tales.

By 1915, there were nearly twenty pulp magazines on America’s newsstands. Most were general or spicy fiction titles such as The Argosy, All-Story Weekly, The Blue Book Magazine, Railroad Man’s Magazine, Short Stories, and Snappy Stories. They were often displayed on the same racks as the remaining nickel weeklies, story papers, and dime novels.

With the growing success of their pulp magazine line — Live Stories, New Story Magazine, People’s, The Popular Magazine, and Top-Notch Magazine — Street & Smith began to stir the pot. With their weeklies and story papers on the wane, the publisher began to convert their formerly venerable titles to the pulp format. First to go was New Tip Top Weekly, the home of Frank Merriwell and his family and friends. With its March 10, 1915 number, it was converted to a pulp, initially entitled Tip Top Semi-Monthly. Later that same year, it would be retitled Wide-Awake Magazine. Under both names, it was edited by Gilbert Patten, hiding behind the Standish name. Unfortunately, whatever the title, the magazine was gone by the summer of 1916.

With the growing success of their pulp magazine line — Live Stories, New Story Magazine, People’s, The Popular Magazine, and Top-Notch Magazine — Street & Smith began to stir the pot. With their weeklies and story papers on the wane, the publisher began to convert their formerly venerable titles to the pulp format. First to go was New Tip Top Weekly, the home of Frank Merriwell and his family and friends. With its March 10, 1915 number, it was converted to a pulp, initially entitled Tip Top Semi-Monthly. Later that same year, it would be retitled Wide-Awake Magazine. Under both names, it was edited by Gilbert Patten, hiding behind the Standish name. Unfortunately, whatever the title, the magazine was gone by the summer of 1916.

A more successful conversion would occur during the fall of 1915 when Nick Carter Stories became Detective Story Magazine, beginning with its October 5 number. The first successful specialized all-fiction pulp, Detective Story Magazine was edited by Frank E. Blackwell, hiding behind the fictitious Nicholas Carter name.

Street & Smith would successfully repeat the conversion process about four years later when New Buffalo Bill Weekly became Western Story Magazine with its July 12, 1919 issue. Next, looking for success in the women’s market, Love Story Magazine debuted in the spring of 1921. Sea Stories Magazine was launched in early 1922.

Street & Smith would successfully repeat the conversion process about four years later when New Buffalo Bill Weekly became Western Story Magazine with its July 12, 1919 issue. Next, looking for success in the women’s market, Love Story Magazine debuted in the spring of 1921. Sea Stories Magazine was launched in early 1922.

Thanks to the feats of All-American halfback Red Grange, Babe Ruth, the “Sultan of Swat,” heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey, tennis star “Big Bill” Tilden, and Man o’ War, the greatest racehorse of them all, interest in organized sports was growing. So come late summer in 1923, Sport Story Magazine rounded the bases for the first time.

It took Street & Smith a full five issues to get their sports pulp onto the diamond. Filling the pulp during its initial issues were reprints of sports fiction from People’s Ideal Fiction Magazine, The Popular Magazine, and Top-Notch. Only with the sixth issue does one find much original fiction in the magazine — a football story by Bill Brandt, a boxing yarn by William Henry Cook, and a tale of auto-racing by Frank X. Finnegan. Cook would become a fixture in the magazine for most of its first decade, while the long-running feature, “From the Bleachers,” would debut in the December 8, 1923 issue.

As late as the summer of 1926, one finds more than a few reprints in the pages of the Street & Smith sports pulp. Joining Bill Cook among the regular contributors to the magazine were Charles Dana Bennett, Sam Carson, Tom Curry, Harold de Polo, Cliff Farrell, Herbert Louis McNary, Kingsley Moses, Gilbert Patten, the world champion sprinter Jackson Scholz, Moran Tudury, and future Black Mask great Raoul Whitfield. Both T. W. Ford and Arthur Mann would also become regulars in 1931. Each would contribute over 100 stories to Sport Story Magazine. Also in 1931, Robert E. Howard would place his three “Kid Allison” boxing stories with the magazine.

As late as the summer of 1926, one finds more than a few reprints in the pages of the Street & Smith sports pulp. Joining Bill Cook among the regular contributors to the magazine were Charles Dana Bennett, Sam Carson, Tom Curry, Harold de Polo, Cliff Farrell, Herbert Louis McNary, Kingsley Moses, Gilbert Patten, the world champion sprinter Jackson Scholz, Moran Tudury, and future Black Mask great Raoul Whitfield. Both T. W. Ford and Arthur Mann would also become regulars in 1931. Each would contribute over 100 stories to Sport Story Magazine. Also in 1931, Robert E. Howard would place his three “Kid Allison” boxing stories with the magazine.

Occasional contributors during this period included Arthur J. Burks, Paul Chadwick, Carroll John Daly, Laurence Donovan, J. Allan Dunn, Paul Gallico, L. Patrick Greene, Ernest Haycox, Robert J. Hogan, C. S. Montanye, Frank Richardson Pierce, and tennis star Bill Tilden. 1932 would feature a three-part football serial, “Thunderbolt,” written by Max Brand, as well as a pair of short stories attributed to Maxwell Grant, the house name behind The Shadow.

During the magazine’s second decade, the mainstays of fiction writing were T. W. Ford, Arthur Mann, and Jackson Scholz. Joining the trio were Robert N. Bryan, Bruce Dunn, David Garth, Dabney Horton, Leonard Lupton, Leslie McFarlane, Franklin P. Miller, Ross Russell, and Stanley Vickers. Occasional contributors included William R. Cox, Harold F. Cruickshank, Jack Kofoed, and Charles Spain Verral. During this period, there was also a marked increase in the use of the Burt L. Standish byline. However, none of the stories attributed to Standish was a Merriwell yarn. There were also many poems credited to Arthur L. Rafter, the poet laureate of Street & Smith’s Wild West Weekly.

During the magazine’s second decade, the mainstays of fiction writing were T. W. Ford, Arthur Mann, and Jackson Scholz. Joining the trio were Robert N. Bryan, Bruce Dunn, David Garth, Dabney Horton, Leonard Lupton, Leslie McFarlane, Franklin P. Miller, Ross Russell, and Stanley Vickers. Occasional contributors included William R. Cox, Harold F. Cruickshank, Jack Kofoed, and Charles Spain Verral. During this period, there was also a marked increase in the use of the Burt L. Standish byline. However, none of the stories attributed to Standish was a Merriwell yarn. There were also many poems credited to Arthur L. Rafter, the poet laureate of Street & Smith’s Wild West Weekly.

Beginning in the late twenties, the use of non-fiction pieces gradually increased in Sports Story Magazine. This trend gained pace over the pulp’s second decade. “The Locker Room” — “Where the editor and readers meet and talk things over” — debuted in the July 10, 1932 issue. Track and field coach Dean Cromwell contributed the column “Trainer and Coach” throughout 1932 and half of 1933. Features including puzzles, quizzes, and sports factoids found their way into the magazine. There were interviews and biographical sketches of sports figures, as well as “How To” and “Big Moments in Sports” features. Many were penned by Arthur Mann and Arthur Grahame (who also wrote “From the Bleachers” for many years). Ronald Oliphant served as editor for most of the 1930s. He was followed by Charles Moran during the magazine’s final years.

Beginning in the late twenties, the use of non-fiction pieces gradually increased in Sports Story Magazine. This trend gained pace over the pulp’s second decade. “The Locker Room” — “Where the editor and readers meet and talk things over” — debuted in the July 10, 1932 issue. Track and field coach Dean Cromwell contributed the column “Trainer and Coach” throughout 1932 and half of 1933. Features including puzzles, quizzes, and sports factoids found their way into the magazine. There were interviews and biographical sketches of sports figures, as well as “How To” and “Big Moments in Sports” features. Many were penned by Arthur Mann and Arthur Grahame (who also wrote “From the Bleachers” for many years). Ronald Oliphant served as editor for most of the 1930s. He was followed by Charles Moran during the magazine’s final years.

For almost five years, Sport Story Magazine had the sports fiction field all to itself. It wasn’t until the introduction of Fight Stories in mid-1928 that another sports pulp emerged. Over the next 25 years, dozens of sports pulps appeared on the market: Ace Sports, All-American Football Magazine, All-American Sports Magazine, All Sport, Baseball Stories, Best Sports, Complete Sports, Dime Sports Magazine, Exciting Sports, Fifteen Sports Stories, Football Action, Football Stories, New Sports Magazine, Popular Sports Magazine, Sports Action, Sports Fiction, Sports Novels Magazine, Sports Winners, Super Sports, Thrilling Sports, 12 Sports Aces, and about thirty other titles.

For almost five years, Sport Story Magazine had the sports fiction field all to itself. It wasn’t until the introduction of Fight Stories in mid-1928 that another sports pulp emerged. Over the next 25 years, dozens of sports pulps appeared on the market: Ace Sports, All-American Football Magazine, All-American Sports Magazine, All Sport, Baseball Stories, Best Sports, Complete Sports, Dime Sports Magazine, Exciting Sports, Fifteen Sports Stories, Football Action, Football Stories, New Sports Magazine, Popular Sports Magazine, Sports Action, Sports Fiction, Sports Novels Magazine, Sports Winners, Super Sports, Thrilling Sports, 12 Sports Aces, and about thirty other titles.

What set Sport Story Magazine apart from the rest of the sports pulps was its range of sports covered, as well as the sheer volume of fiction that it published over the years. With 427 issues — plus an annual and one yearbook — it far outdistanced its nearest rivals. Fight Stories ran for 106 issues; Sports Novels Magazine lasted for 85; and Dime Sports Magazine hit 81.

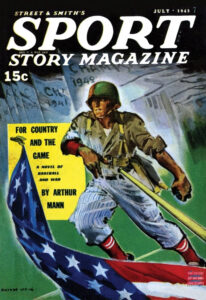

Twenty years after lifting sports fiction out of the dime novels and nickel weeklies, Street & Smith’s Sport Story Magazine was called out on strikes. Its last at-bat was dated July 1943.

Twenty years after lifting sports fiction out of the dime novels and nickel weeklies, Street & Smith’s Sport Story Magazine was called out on strikes. Its last at-bat was dated July 1943.

We hope you’ll join PulpFest 2023 from August 3 – 6 at the DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel Pittsburgh – Cranberry in Mars, Pennsylvania for a celebration of the centennial of Sport Story Magazine.

We’ll have presentations on the Street & Smith sports pulp and its offspring, a look at the sports fiction of Rod Serling, creator of The Twilight Zone, and much more.

You can become a member of the convention by clicking the Registration button on the PulpFest website. And don’t forget to book a room.

If you’d like to learn more about Sports Story Magazine, please visit the PulpFest YouTube Channel and check out Craig McDonald’s video on the magazine. You’ll find it at https://youtu.be/5rDbV3PbJHw. While you’re there, please be sure to subscribe to our channel and be the first in the bleachers to see each video.

The sports fiction field has been lightly studied, particularly the sports pulps. We consulted John Dinan’s Sports in the Pulp Magazines (McFarland & Company, 1998); Michelle Nolan’s Ball Tales (McFarland & Company, 2010); Quentin Reynolds’ The Fiction Factory (Random House, 1955); The FictionMags Index, and the Sports Fiction Index at Phil Stephensen-Payne’s Galactic Central website for this article.

For the section on Frank Merriwell and his creator, we relied on Robert H. Boyle’s “Frank Merriwell’s Triumph,” from the December 24, 1962 issue of Sports Illustrated; the late J. Randolph Cox’s The Dime Novel Companion (Greenwood Press, 2000); Stewart H. Holbrook’s “Frank Merriwell At Yale Again And Again And Again,” from the June 1961 issue of American Heritage; and the William G. Patten entry at the House of Beadle & Adams website hosted by the Northern Illinois University Libraries, DeKalb, Illinois.

We also want to thank David Saunders for his help with artist identification.

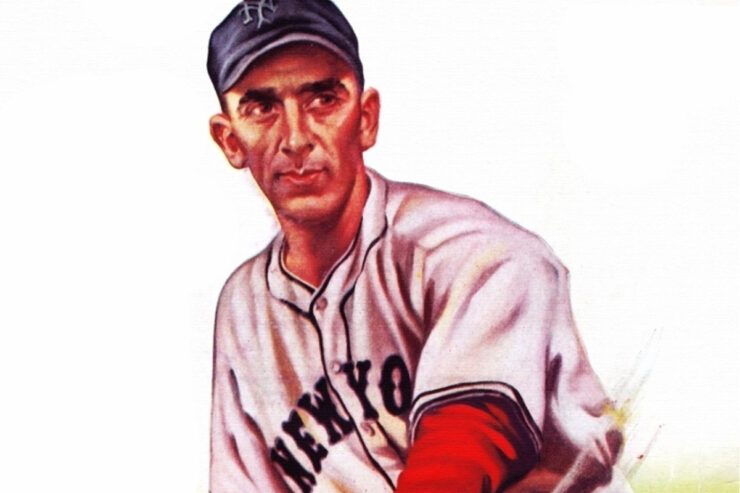

Heading our post is an excerpt from Earle K. Bergey’s cover for the May 25, 1934 issue of Sport Story Magazine, depicting New York Yankee pitcher Carl Hubbell, who is interviewed by Arthur Mann for the issue.

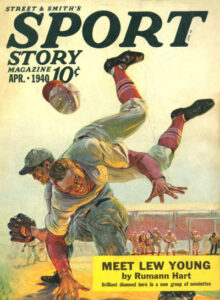

Leading our post is H. Winfield Scott’s cover for the April 1940 issue of Sport Story Magazine. Most remembered for his cover paintings for Street & Smith’s Wild West Weekly, Scott was also one of the leading artists for the sports pulps.

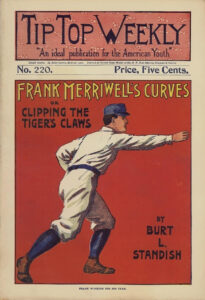

Unfortunately, the cover artist for Tip Top Weekly No. 220, dated June 30, 1900, is not known. Most cover illustrations for the dime novels and story papers are not signed or credited.

Unfortunately, the cover artist for Tip Top Weekly No. 220, dated June 30, 1900, is not known. Most cover illustrations for the dime novels and story papers are not signed or credited.

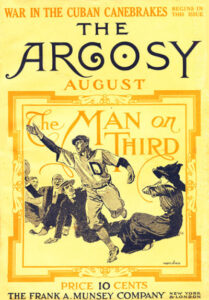

Prior to his extensive work for Street & Smith’s Love Story Magazine, Modest Stein was a leading artist for the Munsey pulps, including The Argosy. Pictured above is his cover for the August 1911 issue of the Munsey magazine. Stein is also represented at the end of our Sports Story Magazine post with his cover for the final issue of the magazine, dated July 1943.

D. C. Hutchison contributed the cover art for the March 15, 1916 issue of Top-Notch Magazine. Born in Scotland, Hutchison was a leading artist for many popular magazines during the first three decades of the twentieth century.

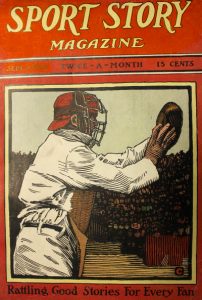

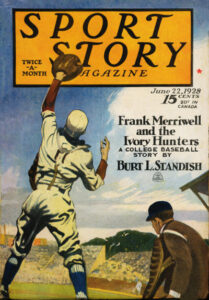

Freeland A. Carter studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. A successful book and magazine artist, he began to contribute to Street & Smith’s Sport Story Magazine as a cover artist and interior illustrator during the pulp’s early years. His work was usually signed only with his initials, “F.A.C.” Above are Carter’s covers for both the September 8, 1923, and the June 22, 1928 issues of Sport Story Magazine.

Although best remembered for his “good girl” cover art for the girlie pulps and Standard Magazine’s science fiction pulps, Earle K. Bergey was one of the leading cover illustrators for the sports pulps. Pictured above is his cover art for the first number of Sport Story Magazine, dated May 1931.

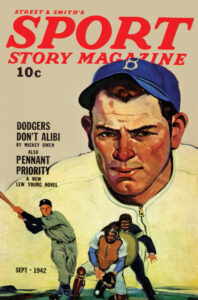

A. Leslie Ross was a freelance artist who worked for just about all of the leading publishers of pulp magazines. His cover art for the September 1942 issue of Sport Story Magazine is a depiction of Mickey Owens, who was a catcher for the Brooklyn Dodgers. In later years, Ross worked for the Hollywood studios, slick magazines, paperback books, and men’s adventure magazines. He also did advertising art and opened a private art school.

Chester Bloom was a leading artist for the sports pulps following the Second World War. He primarily worked for Martin Goodman’s chain of pulp magazines, although he also contributed work to Popular Publications’ Fifteen Sports Stories. In later years, he worked as a portrait artist. Pictured above is his cover for the August 1947 issue of Sports Action, published by Goodman’s Manvis Publications.

Closing our post is freelance artist Charles DeFeo’s cover for the April 1937 issue of Popular Publications’ Sports Novels Magazine, the first issue of the pulp. As mentioned above, Sports Novels Magazine was one of the nearest rivals to Street & Smith’s Sport Story Magazine, publishing a total of 85 issues. However, that was 342 issues less than the total run of Sport Story, even excluding the annual and the yearbook.

During July and August 1942, just months after the United States entered World War II, magazines nationwide featured the American flag on their covers. Adopting the slogan “United We Stand,” some five hundred publications waved the stars and stripes to promote national unity, rally support for the war, and celebrate Independence Day. Charles DeFeo contributed the cover art for Street & Smith’s “United We Stand” campaign. DeFeo’s artwork appeared across the publisher’s line of pulp magazines, including Sport Story Magazine.