Pulp magazines have influenced writers, artists, film directors, software developers, and countless others over the years. Our “PulpFest Profiles” focus on contemporary creators who have drawn inspiration from these rough-paper fiction magazines.

Sara Light-Waller is an award-winning illustrator, author, graphic designer, journalist and pulp historian, as well as a PulpFest Organizing Committee Member.

Craig McDonald (CMC): Sara, thank you for making time for this discussion of classic and modern pulp literature! What was your gateway to pulp fiction?

Craig McDonald (CMC): Sara, thank you for making time for this discussion of classic and modern pulp literature! What was your gateway to pulp fiction?

Sara Light-Waller (SLW): Thanks so much Craig, I appreciate you taking the time to talk with me. Actually, there were several gateways. The first one was when I was eleven or twelve (that would have been in the mid-late 1970s) when I opened up a couple of Golden Age science fiction compilations from my parent’s library. I have no memory of the authors or titles, but the stories were haunting and I never forgot them. I also read Brave New World by Aldous Huxley at that time. I was much too young to read that book, and it’s not truly pulp, although it was published during the pulp era and mentioned in the pulp magazines of the 1930s.

Starting in my late teens I became a fan of the Ellery Queen mysteries. But by my college years I’d turned to other things and lost sight of pulp-era stories for some time. In 2007 a friend recommended the movie The Last Mimzy to me. After watching it, I felt there was something incomplete about the plot. I went in search of the source material which led me to Henry Kuttner. What a joy to find him! A whole new world opened up for me that day. I’m an obsessive researcher and reader and will read through entire bibliographies, if possible. To date, I’ve read nearly everything Kuttner wrote under all his pseudonyms, with and without C.L. Moore. So you could say that in 2007 my real pulp adventure began.

CMC: Is there a particular subgenre within classic pulp that speaks to you?

SLW: That would be science fiction, first and foremost. But I’m also a huge fan of pulp fantasy, some detective stories, some mystery, some adventure, some love stories, and some weird sorts of tales. Generally, I’ll read across subgenres based on the author. For example, I’ll read anything by Fredric Brown or Robert Leslie Bellem. Besides reading for pleasure, I have the goal of learning how the best pulp writers handled language and plot to assist my own writing. I’m doing a Robert Leslie Bellem stint right now, studying the way he put together language. I’m also a fan of Damon Runyon, another author who twirled words around and made them sit up and do tricks.

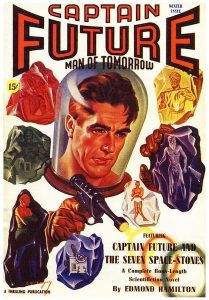

CMC: You’ve indicated Edmond Hamilton, creator of Captain Future, is a favorite author. What about his work most engages you? Has Hamilton influenced your own writing in any way?

SLW: I find his vision of the future simply marvelous. I read somewhere that as a young man he looked up one night and envisioned the universe filled with burning orbs, dark stars, and whirling pinwheels of nebulous gases. I can well imagine this incident as he seemed to see space in a way few others had. His Captain Future stories are fine examples. I don’t really care whether or not they are scientifically accurate or even superscience, when I read them I feel that sense of “wonderfulness” that Robert Lowndes described in reference to the best of the old pulps.

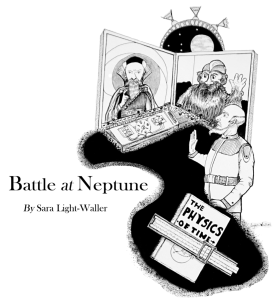

Hamilton’s writing has had a big influence on my own. I re-wrote his ending to “Cosmos” (the science fiction round-robin story published in 1933-34) — “Chapter 17: Armageddon in Space.” My story, “Battle at Neptune” won the 2020 Cosmos Prize. When researching and writing that story I said to myself, Hamilton was called both “World-Wrecker” and “World-Saver” and I’m going to emulate the world-saver.

CMC: You’ve described your work as “neotopian.” Can you elaborate on that? How do you define neotopian?

SLW: You can trace the roots of what I call “neotopia” all the way back to reading Brave New World. Although it was considered a satire for several decades, it was a true dystopian novel. I’ve considered utopias and dystopias for a long time and have found both concepts lacking. True classical utopias and pseudo-utopias are great for the rulers and the elite, but not so good for the lower classes and slaves (although they are not usually called slaves.)

In literature, dystopias are often utopias seen through the eyes of miserably oppressed folks. In utopia, all non-functioning cogs are removed (one way or the other) in order to maintain the perfect society. Alternatively, dystopias are diverse and terrible. Essentially non-functioning in terms of societal growth.

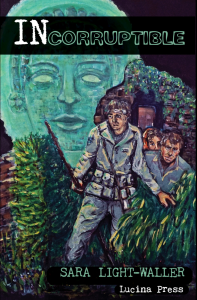

Humans need to make mistakes in order to progress. Organic patterns of learning are non-linear and difficult to control. At root, both utopias and dystopias are anti-humanistic. But a neotopian world is one where humanity learns through trial and error, eventually creating a truly human-centric functional society. Imagine a world where people are celebrated for doing professionally what they have an inborn knack for doing. This is human-centric. You might say that it is also anarchic, but it is not. Some sort of functioning structure for society would develop, organically in this case. But the road to neotopia is messy and many people prefer order, even if it is cruel. But I think the bravery it takes to create neotopia is worth it in the long run. Humans will come out of it stronger and self-realized. My illustrated novelette, Landscape of Darkness shows a world well on its way to neotopia. It takes place about 200 years in our future. My newest novelette — Incorruptible — shows the disaster which eventually leads humanity toward a neotopian future.

Humans need to make mistakes in order to progress. Organic patterns of learning are non-linear and difficult to control. At root, both utopias and dystopias are anti-humanistic. But a neotopian world is one where humanity learns through trial and error, eventually creating a truly human-centric functional society. Imagine a world where people are celebrated for doing professionally what they have an inborn knack for doing. This is human-centric. You might say that it is also anarchic, but it is not. Some sort of functioning structure for society would develop, organically in this case. But the road to neotopia is messy and many people prefer order, even if it is cruel. But I think the bravery it takes to create neotopia is worth it in the long run. Humans will come out of it stronger and self-realized. My illustrated novelette, Landscape of Darkness shows a world well on its way to neotopia. It takes place about 200 years in our future. My newest novelette — Incorruptible — shows the disaster which eventually leads humanity toward a neotopian future.

CMC: You’re an author and an illustrator. Tell us about the shadow-play between the two. Also, does story come first, or are you perhaps seized by an image that becomes an illustration which in turn inspires a prose work?

SLW: An excellent question! I’m very fortunate that I can play the two off each other. For the most part, the story informs the illustration, but not always. Sometimes a visual cue can inspire a scene, or create the need for a change in a scene. Sometimes, I can only write a character after I’ve drawn them.

I am an incredibly visual writer, meaning that I see the story playing out in my head like a movie as I’m writing it. However, at times the imagery is so complex that I must draw it out before I can accurately describe it.

CMC: You’ve stated that you have an interest in the art techniques used by pulp illustrators, especially for interior artwork. Can you tell us something about that?

SLW: I consider myself a historian and that includes illustration techniques. One of my goals is to preserve (and teach when I can) the vanishing illustration techniques from the pre-digital days. I prefer to use period techniques and media to illustrate my new pulp stories.

I had the great good fortune to study scientific illustration back in the late 1980s before digital art became standard. This allowed me to learn techniques such as pen & ink, scratchboard, and the fast editorial technique of coquille. Coquille actually refers to a specialty paper, embedded with a pattern. Through the use of China markers or waxy pencils you can quickly add pattern to a pen & ink illustration. In the 1940s this was a commonplace technique used in everything from editorial cartoons to calendars. You also see it used in interior pulp illustrations. Technically, coquille is a technique for getting good-looking work done fast.

Unfortunately, we have lost perhaps 80% of the types of specialty illustration papers that were used back in the mid-twentieth century. This includes a wide variety of coquille-patterned papers. Fortunately, we still have one brand of coquille paper available on the market today. However, I live in hope of one day discovering a cache of old illustration paper hidden in someone’s (dry) attic.

Unfortunately, we have lost perhaps 80% of the types of specialty illustration papers that were used back in the mid-twentieth century. This includes a wide variety of coquille-patterned papers. Fortunately, we still have one brand of coquille paper available on the market today. However, I live in hope of one day discovering a cache of old illustration paper hidden in someone’s (dry) attic.

CMC: When working in color, is there a particular paint medium you prefer — say, acrylics to oils — or do you move across mediums as inspiration and content might demand?

SLW: For color I use a wide variety of traditional media, with the sole exception of oils. Oil paintings are slow to dry and I don’t have a place to store them. I use water media instead — acrylics, casein, watercolor, and gouache. All of these techniques have their places and I use them for different things, sometimes in combination. For example, acrylics are very vibrant and can mimic the brightness seen in pulp cover art. Casein (a milk-based paint) is a period technique which you see used in interior color illustrations for the slicks. I suspect it was also used for some pulp covers, notably some westerns from the 1920s. Watercolor and gouache were used more than you’d think in the pulps — on Argosy covers from the 1930s, for example.

Sometimes, I’ll use more modern art tools to help create the look of a pulp subject. I may use colored inks, colored pencils, or even water-soluble art crayons to get the right density when reproducing a pulp cover. However, few of these techniques are archival. The color will fade with time. If I’m concerned about lightfastness I’ll steer away from these techniques and stick with acrylics.

CMC: You’ve also created coloring books. Any possibility of a coloring book featuring public domain — or your own version of non-public domain — pulp characters?

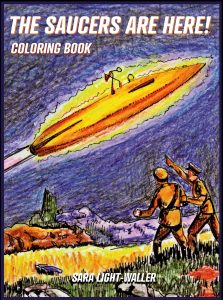

SLW: Absolutely! My latest coloring book is called, The Saucers Are Here! It’s based on Fate magazine covers. In the future, I could see doing a pulp space opera coloring book, and/or a coloring book based on images from the old pulp covers which are now in the public domain. Personally, I think a coloring book of classical space ships would be fun. The designs you see in the old Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon comic strips are an example. I’d adore doing a Captain Future coloring book with my interpretations of the characters based on the original magazine illustrations and covers.

CMC: Apart from penning many fine articles profiling the works of classic pulp authors and illustrators for pulp journals and websites, you also use your social media postings for similar purposes in terms of providing followers small bursts of pulp history. How much time would you say you devote to your pulp scholarship? What are your favored reference sources or research tactics?

SLW: I do casual research all the time. Years ago I noticed that most people’s impressions of the pulps were under-dressed women on the covers of smut paperbacks. It would be a logical conclusion that as a pulp fan I was into smut, which I am not. I’ve made it a personal mission to educate my fans and followers about the pulps — all the wonderful stories and illustrations about adventure, heroism, and love.

I’m completely in line with Robert Lowndes’ concept of “wonderfulness,” that elusive quality that permeated the very best of the old pulp stories. In 1956 Lowndes wondered, “. . . are there writers today who have that personal feeling of wonderfulness without which the needed element cannot be present in their writing?” I’d like to answer him in 2022 with a raised hand. Coincidentally, for decades my studio’s motto has been “bring back the wonder.”

As far as favored reference sources I like to go back to the original magazines when I can. The internet is wonderful for information, although there’s a lot of copying and pasting endlessly from site to site. That said, there are many valuable compilation sites such as Galactic Central and the Internet Speculative Fiction Database both of which I use all the time. I also have the usual sorts of pulp research books in my library at home.

CMC: What can we look forward to next from Sara Light-Waller?

SLW: I have several things in the works right now. I’m writing a non-fiction book about pulpster Bryce Walton. Walton was a prolific writer for the magazines but as he wrote little in the way of full-length novels he is not often reprinted. He wrote extensively about dystopias, some of which are eerily similar to things we are seeing today.

In fiction, I’m writing a companion piece to my illustrated short story, “ANCHOR: A Strange Tale of Time.” The new illustrated novella will be the “he-said” story to ANCHOR’s “she-said” tale. I plan to repackage both stories (with a new cover for ANCHOR) back to front as a sort of Ace Double.

In fiction, I’m writing a companion piece to my illustrated short story, “ANCHOR: A Strange Tale of Time.” The new illustrated novella will be the “he-said” story to ANCHOR’s “she-said” tale. I plan to repackage both stories (with a new cover for ANCHOR) back to front as a sort of Ace Double.

I also have a longer novel series in process, a superhero science fantasy. The first of these will come out in 2023, I think. All four books are already written and in the editing process.

There will also be new paintings . . . not just book covers and illustrations but a continuation of my “New Pulp Series” featured on my Flying Pony Studios website. My quest to become a better pulp painter is never-ending and I expect to add a few more paintings to my sale list this winter.

Want to learn more about Sara Light-Waller and her work? Her official websites are Lucina Press and Flying Pony Studios. She’s also on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Sara posts regular updates about her books on her Lucina Press blog and about her art on the Flying Pony Studios blog. Sara posts on social media regularly. A member of the PulpFest organizing committee, you can read more about Sara on our PulpFest Committee page.

A professional journalist and illustrator with over thirty years of experience, Sara Light-Waller is an accomplished new-pulp fiction author/illustrator with two books out and more on the way. She is also the winner of the 2020 Cosmos Prize for her illustrated short story, “Battle at Neptune.” A huge pulp fan, Sara is especially fond of science fiction pulps. The extent of her pulp fandom can best be measured by the oversized rendition of Frank R. Paul’s August 1928 Amazing Stories cover that she painted on her garage. Sara is a member of the PulpFest organizing committee and a regular contributor to our website and The Pulpster.

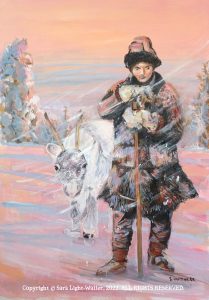

A longtime fan of Edmond Hamilton’s Captain Future — pictured above is Earle K. Bergey’s cover for the Winter 1941 issue of Standard Publications’ Captain Future. Check out her “PulpFest History” article, “Eighty Years of Captain Future,” and her “PulpFest Profile,” “Allen Steele — Captain Future and Beyond.” Her latest novella, Incorruptible, was published in the late summer of 2022. Her cover art for the book was inspired by Dalton Stevens’ work for Macfadden’s Ghost Stories. The final image of our post — entitled “The Devil’s Pet” — is Sara’s tribute to Stevens’ Ghost Stories covers. Her “Cold North” image is a tribute to the wonderful covers of Adventure magazine.

Sara’s black-and-white illustration for her award-winning story, “Battle at Neptune,” was inspired by the artist and illustrator Edd Cartier. Her The Saucers Are Here! coloring book was published in the late summer of 2022 and premiered at the Flying Saucer Party in Chehalis, Washington.

Author of the Edgar-nominated Hector Lassiter historical crime series, Craig McDonald is an award-winning novelist, journalist, and editor. The Hector Lassiter series chronicles the exploits of a fictional Black Mask author and his encounters with such notable figures as Ernest Hemingway, Orson Welles, Ian Fleming, and Lester Dent. McDonald’s internationally acclaimed works have found a global audience and have also been adapted in graphic novel format. His works have been published by Simon & Schuster and Macmillan Press. A member of the PulpFest organizing committee and a regular contributor to our website and The Pulpster, you can read more about Craig on our PulpFest Committee page.

Watch for our next PulpFest Profile on December 12 when Sara Light-Waller will talk with the licensed continuation author for the Sax Rohmer Literary Estate, William Patrick Maynard. Bill is also a member of the PulpFest Organizing Committee and serves as Assistant Director of Marketing and Afternoon Programming Director.