“Finding out the truth about a legend builder . . .

is like trying to chew your way into a coconut.

The husk of fiction is very solid and hard to penetrate.”

— WILLIAM LINDSAY GRESHAM

It’s one of my favorite crime novels.

It’s one of my favorite crime novels.

It’s the only transcendent piece of writing its author ever committed to paper.

But how many writers achieve even a single masterpiece?

William Lindsay Gresham, a sometimes pulp magazine writer and one-hit-wonder hardcover novelist, is getting some fresh cinema love from director Guillermo del Toro with his film adaptation of Gresham’s Nightmare Alley, set to debut December 17. It’s being described as a neo-noir psychological thriller.

Like Cornell Woolrich, David Goodis, and a few doomed others, William Lindsay Gresham was never going to be a centenarian. Like his masterpiece, his was a noir life . . .

Bill Gresham was born in Baltimore on Aug. 20, 1909. His family fled Maryland for New York. There Bill found the Coney Island sideshow and his eventual writerly milieu.

He later wrote: “Coney Island, before the First World War, was a raucous, blaring playground… Here, for the first time, I saw women with painted mouths on the streets in broad daylight… At the island, the cops were well taken care of; the joint was running wide open. And to me, even under the handicap of a starched Buster Brown collar, a day at Coney Island was paradise.”

But Bill would be a while getting to write about all that. Like Chandler, like Ian Fleming, he was a late-blooming novelist and would be nearly forty years old before publishing his one great book.

First, he bummed around. Greenwich Village busker… Spanish Civil War medic… TB ward habitué and a failed attempt at completing suicide by hanging himself.

During the 1940s, he began to sell to the pulp magazines. You can find a smattering of stories here and there, including one that appeared in Doc Savage more than 70 years ago. Entitled “The Coffin Cult,” it was published under the by-line “W. L. Gresham.” Others appeared in Blue Book; another in Giant Western. He also placed stories with Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Fantastic, Manhunt, and other digests, and later contributed to men’s magazines such as Dude, The Gent, and Rogue.

During the 1940s, he began to sell to the pulp magazines. You can find a smattering of stories here and there, including one that appeared in Doc Savage more than 70 years ago. Entitled “The Coffin Cult,” it was published under the by-line “W. L. Gresham.” Others appeared in Blue Book; another in Giant Western. He also placed stories with Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Fantastic, Manhunt, and other digests, and later contributed to men’s magazines such as Dude, The Gent, and Rogue.

He married poet Joy Davidman, his second wife, and had a couple of kids. It wasn’t a happy or lasting union. Joy eventually lighted out from her alcoholic husband, running to writer C.S. Lewis (an affair dramatized in the film Shadowlands).

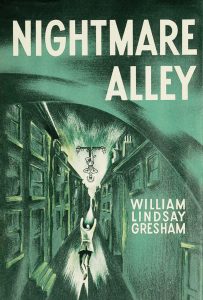

In 1946, casting back to his longstanding fascination with the midway, Gresham wrote the classic carnival noir Nightmare Alley. The novel made him fleetingly rich.

Nightmare Alley tells the story of a smalltime grifter, Stan Carlisle, and his rise from tent show mentalist to A-list attraction, the kind of pitiless ascent required to set up a terminal-velocity crash-dive to the deepest depths of the pit.

It opens: “Stan Carlisle stood well back from the entrance of the canvas enclosure, under the blaze of a naked light bulb, and watched the geek.”

Twenty-two chapters later, we’re in another sideshow tent. In the novel’s closing paragraph, we’re again confronted with a chicken-head biting geek. Between those two paragraphs dwells one of the blackest noirs.

A year after its publication, Tyrone Power, looking for a meaty role for himself, optioned and filmed the novel. The 1947 screen production doesn’t match the grit of the original novel but that first cinema version of Nightmare Alley stands as a twisted and powerful piece of film noir.

But Gresham, the fiction author, had already peaked.

In ’49, he published his only other novel, Limbo Tower, a misfire set in a TB clinic that one critic described as a “pulp version” of Thomas Mann’s novel, The Magic Mountain.

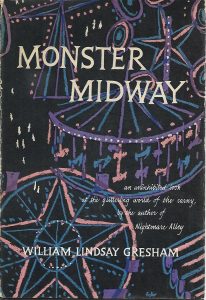

In 1954, Gresham cobbled together articles written for a batch of slick magazines and constructed a nonfiction meditation on the carnival he called Monster Midway, effectively establishing himself as the poet laureate of the mitt camps, flat stores, and alibi joints.

The book’s jacket flap bio makes Gresham sound like a bonhomie guy gushing joie de vivre: “He is an expert knife thrower, magician, ‘mind reader’ and has tried his hand at fire-eating.”

The dust jacket photo doesn’t embody that man.

Instead, it depicts a big-eared, ferret-faced man who looks older than his years. He’s got a pencil-thin mustache, slitted eyes and he’s wearing a trench coat and fedora. His smile is pained.

Instead, it depicts a big-eared, ferret-faced man who looks older than his years. He’s got a pencil-thin mustache, slitted eyes and he’s wearing a trench coat and fedora. His smile is pained.

There’s a faint overlay of derision there, too.

His marriage will soon fail. Bill will move on to his ex-wife’s first cousin, eventually join AA, and slide into spiritualism.

Yet Bill’s still pining for the carnival.

He closes Monster Midway with a letter from a carny friend trying to lure Bill out onto the road: “I got a swell-break this spring, a seal boy… He’s a real good seal-boy, no legs, only stumps of feet and hands coming out of his shoulders. He can shave himself fine… If you can ever pry yourself loose from that typewriter of yours why don’t you wire me and hop a plane out here? Why don’t you give in, kid, and admit it? You’re a carny at heart.”

Bill didn’t run away with that circus.

He delved into nonfiction again in ’57 — a fairly dispensable biography on Houdini written with the assistance of magician and professional debunker James Randi.

Gresham’s last piece of published writing was a bewildering book on body-building — the few surviving photos of the author do not support the concept of Gresham as any form of a fitness freak.

Bill was on his way down, a doom-laden spiral to rival the one he fashioned for “Stanton the Great” Carlisle in that one brilliant novel.

It’s 1962: Bill’s vision is fading. The former fire-eater is diagnosed with cancer of the tongue. It’s less than twenty years since his best-selling debut novel hit the stands.

He’s tried suicide before.

In September ’62, he checks into the Dixie Hotel that he haunted while composing Nightmare Alley. He registers under the name, “Asa Kimball, of Baltimore.” He’s 53, on a suicide run, and this time he means to get it right.

On September 14, Bill succeeds, felled by a fistful of sleeping pills.

In Monster Midway, Gresham opens a chapter with the suicide of a magician famed for his bullet-catching trick. Change just a few details, and the vignette could stand as Gresham’s own death notice.

In Monster Midway, Gresham opens a chapter with the suicide of a magician famed for his bullet-catching trick. Change just a few details, and the vignette could stand as Gresham’s own death notice.

“Showman and recluse, genius and brooding adolescent, solitary drinker and mystifier of crowds, (he) had given up the battle with the dragons of his own mind. He left behind him an odd assortment of friends, few of whom knew each other, for he kept his social circles from overlapping.”

Grim? Sure.

But noir and happy endings aren’t acquainted.

They say Bill’s death didn’t get much attention, went largely unnoticed by the press other than a bridge columnist.

The centenary of his birth also went largely unremarked upon.

But he had that one great novel, and now, a second film adaptation of the same.

That’s something…

Right?

The jacket design for William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley, published in 1946 by Rinehart & Company, was by A. F. Arnold, an American graphic artist & toy designer. Sue Foster designed the dust jacket for Monster Midway, published by Rinehart & Company in 1953.

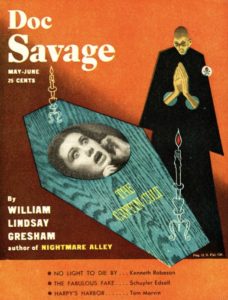

Interestingly, when Bill Gresham’s short story, “The Coffin Cult,” appeared in the May/June 1947 issue of Doc Savage, the Doc Savage novel, “No Light to Die By,” didn’t even get the cover illustration that was created by an uncredited artist. Instead, Gresham’s short story was spotlighted. Below is the pitch for that story made within the magazine:

“It’s hard to say just how many novels are published every year. At any rate, it’s unusual when one is remembered beyond its time, or when it stays consistently on best-seller lists. NIGHTMARE ALLEY by William Lindsay Gresham is one of the exceptions. It sold fabulously well, aroused glowing critical comment, and convinced the American public that a new novelist was born.

“When we ordered THE COFFIN CULT, Mr. Gresham was still living in the East. Now he’s in Hollywood, working on the movie to be made out of NIGHTMARE ALLEY… so he’s not writing any magazine stories at the moment. That’s why THE COFFIN CULT is doubly interesting: for its own sake, and for its status as one of the last stories Bill Gresham wrote before he achieved the kind of success every writer dreams of but seldom attains.

“Those of you who read NIGHTMARE ALLEY — as well as those of you who are meeting William Lindsay Gresham for the first time — will get a kick out of THE COFFIN CULT!”