The stories and art of the pulp magazines have had a profound effect on popular culture across the globe. They have reverberated through a wide variety of media — comic books, movies, paperbacks and genre fiction, television, men’s adventure magazines, radio drama, and even video, anime, manga, and role-playing games.

The stories and art of the pulp magazines have had a profound effect on popular culture across the globe. They have reverberated through a wide variety of media — comic books, movies, paperbacks and genre fiction, television, men’s adventure magazines, radio drama, and even video, anime, manga, and role-playing games.

Although science fiction can trace its roots to the imaginary voyages, satires, and utopias of the seventeenth century, scholars have repeatedly pointed to Mary Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN — originally published in 1818 — as the first science-fiction novel. Twenty-five years later — beginning with “MS. Found in a Bottle” — Edgar Allan Poe began to use logic and science to explain elements of his fantastic stories. The strength of Poe’s stories inspired authors around the world. One was Jules Verne, who introduced “precise, scientific details” into FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON, TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA, and other tales.

As the 19th century progressed and more people were reading, magazines naturally developed a wider audience. For the more literary, there were titles such as BLACKWOOD’S MAGAZINE and HARPER’S NEW MONTHLY. For those with less refined tastes, there were dime novels, penny-dreadfuls, and story papers. It was in these publications that the “American Jules Verne,” Luis Senarens, developed the Frank Reade, Jr. series that featured steam-powered contraptions in exciting adventure yarns. During the late nineteenth century, the thrilling yarns of Robert Louis Stevenson and H. Rider Haggard, and later, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and H. G. Wells, helped to develop a market for the British popular fiction magazine. The United States would follow in late 1896 when Frank A. Munsey converted THE ARGOSY to an all-fiction, rough-paper magazine.

From its start as a pulp, THE ARGOSY was home to fantastic fiction, reprinting a dystopian short story in its first issue. Other works featured by the magazine included Park Winthrop’s “The Land of the Central Sun” and William Wallace Cook’s “A Round Trip to the Year 2000.”

From its start as a pulp, THE ARGOSY was home to fantastic fiction, reprinting a dystopian short story in its first issue. Other works featured by the magazine included Park Winthrop’s “The Land of the Central Sun” and William Wallace Cook’s “A Round Trip to the Year 2000.”

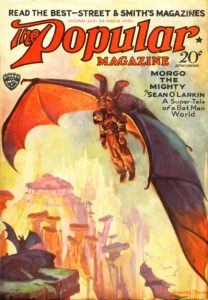

Selling in the hundreds of thousands, THE ARGOSY was bound to generate imitators. Street & Smith — the longtime publisher of dime novels and story papers — was first to meet the call, debuting THE POPULAR MAGAZINE with its November 1903 issue. Munsey himself would be next in line, introducing THE ALL-STORY in late 1904.

More than any other pulp prior to the introduction of the science fiction and fantasy fiction magazines, THE ALL-STORY became the major repository for the “different” tale, the pseudo-scientific yarn, the scientific romance, or the “off-the-trail” story. In its February 1912 issue, the Munsey pulp would begin serializing Edgar Rice Burroughs’ “Under the Moons of Mars.” The author would follow with “Tarzan of the Apes,” published in its entirety in the October 1912 number.

Burroughs’ two classics, along with the pseudo-scientific works of H. G. Wells and his American counterpart, George Allan England, would serve as templates for much of the science fiction written over the next twenty-five years, generating a type of story best known as “the scientific romance.” THE ALL-STORY editor Robert H. Davis, in particular, worked to develop this school of fiction, creating a stable of writers who could contribute such stories. Davis can very well be thought of as “The Grandfather of Science Fiction.”

Although the scientific romances published in the Munsey pulps remained popular, beginning in late 1915, a trend toward specialized magazines slowly emerged. Street & Smith’s DETECTIVE STORY MAGAZINE was the first successful specialty pulp. Over the next decade, magazines specializing in western fiction, love stories, sea yarns, and sports fiction would follow. In early 1923, a pulp devoted to the fantasy and horror genres — WEIRD TALES — would be launched.

In addition to publishing some of the best fantasy and supernatural fiction of the twentieth century, WEIRD TALES, like the Munsey magazines, featured science fiction in its pages. Edmond Hamilton — who began selling to the magazine in 1926 — was the pulp’s leading contributor of science fiction. With tales of super-science about alien invasions, space police, and evolution gone wild, the author became known as “World-Wrecker” Hamilton. Other notable science fiction contributors included Austin Hall, Otis Adelbert Kline, Frank Belknap Long, C. L. Moore, Donald Wandrei, Jack Williamson, and H. P. Lovecraft, spinning his own brand of science fiction in tales of cosmic horror.

Although science fiction was frequently found in its pages, WEIRD TALES was not the first specialized science fiction magazine. That was left for Hugo Gernsback to develop. Called “The Barnum of the Space Age” in 1963, Gernsback came to the United States in 1904. He began importing electronic parts and equipment and sold them via mail order catalog. Gernback’s catalog soon evolved into a magazine, MODERN ELECTRICS, selling for ten cents. In 1911, it began publishing fiction, serializing Gernsback’s own story, “Ralph 124C 41+,” in twelve parts.

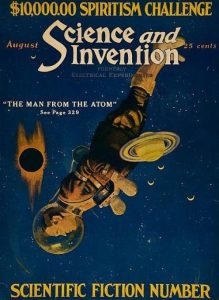

In the spring of 1913, Gernsback began publishing a new science periodical, THE ELECTRICAL EXPERIMENTER. Before long, it was also publishing fiction alongside technical articles. Beginning with its August 1920 number, Gernback’s magazine became SCIENCE AND INVENTION.

The scientifically-trained Gernsback was committed to educating his audience about science and technology through the fiction he published. That all changed in early 1923 when — perhaps in an effort to boost circulation or to test the waters in the growing market for specialized fiction magazines — Gernsback began publishing fiction that was meant to entertain. He reprinted two short works by H. G. Wells, and later, new works by George Allan England and Ray Cummings. The August 1923 issue of SCIENCE AND INVENTION was a “Scientific Fiction Number.” It featured six “scientifiction” stories including “The Man from the Atom,” a short story by a new author, sixteen-year-old G. Peyton Wertenbaker.

The scientifically-trained Gernsback was committed to educating his audience about science and technology through the fiction he published. That all changed in early 1923 when — perhaps in an effort to boost circulation or to test the waters in the growing market for specialized fiction magazines — Gernsback began publishing fiction that was meant to entertain. He reprinted two short works by H. G. Wells, and later, new works by George Allan England and Ray Cummings. The August 1923 issue of SCIENCE AND INVENTION was a “Scientific Fiction Number.” It featured six “scientifiction” stories including “The Man from the Atom,” a short story by a new author, sixteen-year-old G. Peyton Wertenbaker.

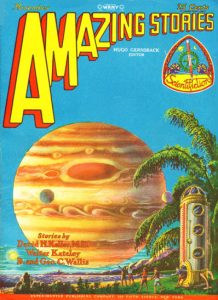

SCIENCE AND INVENTION and his other technical magazines were mere stepping stones for Hugo Gernsback. In the spring of 1926, he introduced a full-fledged science fiction — or as he then termed it, “scientifiction” — magazine. It was hard to miss the first issue of AMAZING STORIES — dated April 1926 — on the newsstand. It was larger than the typical pulp magazine. Vivid, three-dimensional block letters trailed across its masthead, set against a bright yellow backdrop. Frank R. Paul’s cover art depicted a number of ice skaters, gliding in front of snow heaps crowned by two stranded sailing vessels. Looming behind this scene was a bright red, ringed planet and a small moon.

In 1987, the late Jack Williamson wrote: “I don’t think anybody today can entirely understand what it meant to me and many like me then . . . but we found sheer wonder in AMAZING STORIES, a rich new revelation of exciting things to come, a dazzling vision of new ideas and discoveries and inventions that could push our future frontiers wider, make all our lives richer.”

Within months of its introduction, AMAZING STORIES was selling over 100,000 copies of each issue. In establishing the first specialized science-fiction magazine, Gernsback had tapped a vein of wonder shared by lonely individuals scattered across the country, all of them prone to “imaginative flights of fancy.”

The names on the front covers of the early AMAZING STORIES were certainly major selling points: Edgar Rice Burroughs, A. Merritt, Edgar Allan Poe, Garrett P. Serviss, Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, and others. Gernsback also offered story contests. These helped him to acquire a stable of new writers willing and able to write scientifiction: Miles J. Breur, Clare Winger Harris, David H. Keller, S. P. Meek, H. Hyatt Verrill, Harl Vincent, and others. Through the AMAZING STORIES letter column — “Discussions” — Hugo Gernsback also reeled readers into his world of wonder.

With the August 1928 number of AMAZING STORIES, Gernsback introduced his readers to E. E. “Doc” Smith’s “The Skylark of Space.” Also appearing in the issue was Philip Francis Nowlan’s “Armageddon — 2419 AD,” the first tale to feature Buck Rogers. These two “space operas” would color science fiction for well over a decade, turning the genre away from the Munsey type of story — popular with a wide range of readers, both male and female — and toward “that crazy Buck Rogers stuff.”

With the August 1928 number of AMAZING STORIES, Gernsback introduced his readers to E. E. “Doc” Smith’s “The Skylark of Space.” Also appearing in the issue was Philip Francis Nowlan’s “Armageddon — 2419 AD,” the first tale to feature Buck Rogers. These two “space operas” would color science fiction for well over a decade, turning the genre away from the Munsey type of story — popular with a wide range of readers, both male and female — and toward “that crazy Buck Rogers stuff.”

Although he introduced AMAZING STORIES QUARTERLY in the winter of 1928, Hugo Gernsback was increasingly experiencing cash flow problems. Plowing money into his radio interests and paying very hefty salaries to his brother and himself, Gernsback’s Experimenter Publishing Company was forced into bankruptcy.

Although down but not out, Hugo Gernsback used assets tied to his importing and radio businesses to launch a new larger-sized pulp in May 1929. Called SCIENCE WONDER STORIES, Gernsback called the stories in his new magazine, “science fiction.” Unlike “scientifiction,” this name would stick.

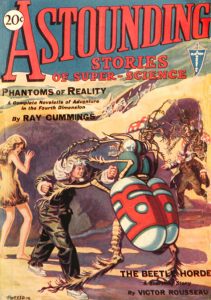

With the growth of the science fiction field — both AMAZING and SCIENCE WONDER also issued quarterlies — other publishers began to notice the field. William Clayton — publisher of SNAPPY STORIES, RANCH ROMANCES, and other titles — was the first to take a bite. Not enamored with the Gernsback style of science fiction, Clayton was more interested in stories of action and adventure . . . “that crazy Buck Rogers stuff.” His new magazine would be called ASTOUNDING STORIES OF SUPER-SCIENCE. According to Alva Rogers:

“ASTOUNDING was unabashedly an action adventure magazine and made no pretense of trying to present science in a sugar-coated form . . . The amount of science found in its pages was minimal – just enough to support the action and little more. Lessons in science could be obtained in school or in text books; driving action and heroic adventure was what the reader of ASTOUNDING wanted. Interplanetary wars and space battles, hideous and menacing Bug Eyed Monsters . . . the courage, ingenuity and brains of a single puny man, or small group of men, pitted against the terrible might and overwhelming scientific knowledge of extraterrestrial aliens – with defeat the inevitable fate of the invaders: that was what set the reader’s pulse pounding. . . . Action was the hallmark of ASTOUNDING STORIES OF SUPER-SCIENCE.”

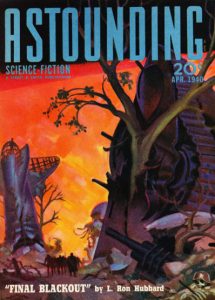

Although the early ASTOUNDING would serve as a repository for space battles and bug-eyed monsters, after it was acquired by Street & Smith in 1933, it would launch what has become known as Science Fiction’s Golden Age. Utilizing writers both old and new, editor John W. Campbell began to set the stage in 1938 and early 1939, publishing such stories as Lester Del Rey’s “Helen O’Loy,” Clifford D. Simak’s “Cosmic Engineers,” Don A. Stuart’s “Who Goes There?” and “Cloak of Aesir,” and Jack Williamson’s “The Legion of Time” and its sequel, “One Against the Legion.”

The July 1939 issue however, is cited most often as the start of the Golden Age of ASTOUNDING and, in turn, of science fiction. Behind a very effective cover by SHADOW cover artist Graves Gladney, the reader would find the first prose fiction by radio soap opera writer A. E. van Vogt as well as the young Isaac Asimov’s first story for ASTOUNDING SCIENCE-FICTION. August’s and September’s issues continued the trend with the first stories of Robert A. Heinlein and Theodore Sturgeon appearing in the magazine. October’s number began the serialization of E. E. Smith’s cosmic adventure, “Gray Lensman,” along with another tale by Heinlein.

The start of the new decade brought with it the flowering of Robert Heinlein as he contributed “Reqiem,” his first novel “If This Goes On—,” “The Roads Must Roll,” and “Blowups Happen.” L. Ron Hubbard’s “Final Blackout” as well as A. E. van Vogt’s “Slan,” were also serialized by Campbell during the year. 1941 continued apace with the first of Heinlein’s works as Anson McDonald—“Sixth Column,” “Solution Unsatisfactory,” and “By His Bootstraps”—as well as “—And He Built a Crooked House,” “Logic of Empire,” “Universe,” and “Methuselah’s Children,” all published under his own name. Heinlein however, was not alone in 1941. Leigh Brackett contributed “Martian Quest;” L. Sprague de Camp offered “The Stolen Dormouse;” Theodore Sturgeon shared “Microcosmic God;” Eric Frank Russell and A. E. van Vogt respectively produced the first tales in their “Jay Score” and “Weapon Shops” series; Isaac Asimov presented “Nightfall” and the first of his robot stories; and E. E. Smith began “Second Stage Lensmen.”

ASTOUNDING SCIENCE-FICTION would continue to publish outstanding works of science fiction throughout World War II and for many years to come. More importantly, it would inspire new magazines dedicated to fantasy and science fiction — GALAXY SCIENCE FICTION, THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION, and others — and older magazines — including AMAZING STORIES and THRILLING WONDER STORIES — to step up their game and publish quality science fiction. We’re still enjoying the results eighty years after that momentous issue of ASTOUNDING SCIENCE-FICTION, dated July 1939.

ASTOUNDING SCIENCE-FICTION would continue to publish outstanding works of science fiction throughout World War II and for many years to come. More importantly, it would inspire new magazines dedicated to fantasy and science fiction — GALAXY SCIENCE FICTION, THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION, and others — and older magazines — including AMAZING STORIES and THRILLING WONDER STORIES — to step up their game and publish quality science fiction. We’re still enjoying the results eighty years after that momentous issue of ASTOUNDING SCIENCE-FICTION, dated July 1939.

Over the last three days, we’ve explored just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the profound effect of the stories and art of the pulp magazines on popular culture. THE SHADOW, WEIRD TALES, and the early science fiction pulps are just a few of the many rough-paper magazines that have inspired pop culture creators over the decades. PulpFest 2019 will focus on the many ways pulp fiction and pulp art have inspired and continue to inspire creators.

We’re calling this year’s theme “Children of the Pulps and Other Stories,” with presentations on Zorro, Dashiell Hammett, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, Sherlock Holmes, THE TWILIGHT ZONE, and more. It’s all part of our examination of the pervasive influence of pulp magazines on contemporary pop culture. We hope you’ll join us from August 15 – 18 at the beautiful DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel Pittsburgh – Cranberry in Mars, Pennsylvania.

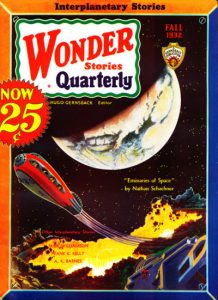

(Soon after starting his monthly SCIENCE WONDER STORIES, Hugo Gernsback debuted a quarterly title. Its first issue was dated Fall 1929. After three quarterly issues, the “Science” was dropped from its title. In his editorial remarks published in the May 1930 issue of SCIENCE WONDER STORIES, Gernsback noted, “It has been felt for some time that the word “Science” has tended to retard the progress of the magazine, because many people had the impression that it is a sort of scientific periodical rather than a fiction magazine.” Although he continued to publish his science fiction magazine, future issues would feature a new title: WONDER STORIES. His quarterly was likewise retitled.

Frank R. Paul painted all of the covers for Hugo Gernsback’s WONDER STORIES QUARTERLY. We believe that that the artist’s cover for the Fall 1932 quarterly aptly depicts the “sheer wonder” that Jack Williamson and other readers found in the early science fiction pulps.

Unlike the Munsey pulps, THE POPULAR MAGAZINE offered a smattering of the fantastic over the years: H. Rider Haggard’s “Ayesha: The Further History of She,” Edgar Wallace’s “The Green Rust,” Fred MacIsaac’s “The Last Atlantide,” and Sean O’Larkin’s “Morgo the Mighty” are a few examples. The latter novel garnered the cover art on three of the four issues in which it was serialized. Howard V. Brown contributed the cover painting for the first installment, which ran in the second August 1930 number. It was one of very few fantastic covers to be featured on the Street & Smith pulp magazine.

Who knows whether the “Scientific Fiction Number” was an effort to boost circulation or to test the waters in the growing market for specialized fiction magazines? Unfortunately, Hugo Gernsback did not share that information. However, we do know that Howard V. Brown painted the cover for the August 1923 issue.

Not long after the appearance of the November 1928 number of AMAZING STORIES — with its wondrous Frank R. Paul cover — Gernsback’s printer demanded payment on past due bills. The publisher filed for bankruptcy. In early 1929, the Experimenter Publishing Company went into receivership. The last issue of AMAZING STORIES to be edited by Hugo Gernsback was dated April 1929.

Prior to creating the cover art for the first issue of ASTOUNDING STORIES OF SUPER-SCIENCE, H. W. Wessolowski had done a half-dozen covers for AMAZING STORIES and its quarterly companion. Beginning with the January 1930 number, he would become the primary cover artist for the Clayton science fiction pulp.

One of the many changes — or “mutations” as he called them — that John W. Campbell instituted at ASTOUNDING after taking over as editor in late 1937, was the hiring of long-time ADVENTURE artist, Hubert Rogers. The free-lance illustrator’s first cover was the February 1939 number. Eventually, he would paint nearly sixty covers for Campbell’s ASTOUNDING, including the April 1940 number, illustrating L. Ron Hubbard’s “Final Blackout.”

To learn more about the influence of the early science fiction pulps, please visit the PulpFest Instagram page.)