Ray Palmer and the AMAZING Shaver Mystery

To many who recall it, the AMAZING STORIES of the 1940s represented the era of the Shaver Mystery. It is probably fair to say that the Shaver phenomenon colored the judgment of many who dismiss the contents of AMAZING during this time as sensationalistic rubbish because of the so-called “crackpot” element that was attracted to the magazine. And crackpots there were, but that is not the whole story.

To many who recall it, the AMAZING STORIES of the 1940s represented the era of the Shaver Mystery. It is probably fair to say that the Shaver phenomenon colored the judgment of many who dismiss the contents of AMAZING during this time as sensationalistic rubbish because of the so-called “crackpot” element that was attracted to the magazine. And crackpots there were, but that is not the whole story.

Raymond A. Palmer, the young new editor of AMAZING at the start of this decade, has been damned by history far more than he deserves — though it must be admitted that in later years he did more or less encourage his isolation. A succession of illnesses and accidents left Palmer a lonely child. One accident left him malformed from a curvature of the spine. In adult life he was only a little more than four feet tall. But what he lacked in height, he made up for in dynamism and showmanship.

One of the factors that led to Palmer’s later isolation was that he started his tenure as editor at the same time that John W. Campbell came on the scene at ASTOUNDING STORIES. Campbell instigated a policy of publishing serious, mature, and above all believable science fiction. He developed a coterie of new writers — including Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Theodore Sturgeon, Lester del Rey, and, believe it or not, L. Ron Hubbard — who could feed off his ideas, as he could feed off theirs. Partly because of these interchanges, the work of these authors ushered in the so-called Golden Age of science fiction.

Palmer, on the other hand, went for fun and games, treating science fiction lightheartedly and aiming at a younger, less sophisticated readership. As a consequence, science fiction polarized between Campbell’s science-forecasters at one extreme and Palmer’s laboratory playpit at the other. That’s not to say that Palmer published only puerile trivia. But because he was science fiction’s renegade, many are ready to dismiss too easily the fiction that he did publish. From today’s vantage point, though, one might argue that under Palmer, AMAZING published a 1940s’ version of “pop” or “punk” science fiction, and its pages during that decade hold some surprises.

At the outset, it must be recalled that Palmer was trying to rebuild AMAZING‘s circulation and rectify years of damage caused by T. O’Conor Sloane’s handling of the magazine. By 1938 AMAZING had stagnated, and Palmer’s first move was to enliven it with bold, gaudy, action-packed covers reflecting the fast-paced, thrill-a-minute contents. When his writers asked what type of fiction he wanted, Palmer’s simple answer was “Gimme bang-bang.” Palmer had little time for the cerebral style of sf that was emerging in ASTOUNDING. He wanted superficial, escapist enjoyment, similar to the scientific romances that the pulp magazines had published before Hugo Gernsback launched AMAZING STORIES in 1926, but less sophisticated.

Palmer wanted to recapture the fun of the early pulps. He was fortunate in being able to secure three groups of stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs, set respectively in his worlds of Mars, Venus, and Pellucidar. These ran through 1941 and 1942. Although Burroughs’s fortunes had declined in recent years, his name still captured the imagination of old and young alike. The first appearance of an original Burroughs story in AMAZING, however, caused a controversy. The January 1941 issue carried the novelette “John Carter and the Giant of Mars,” but many readers, who were dedicated Burroughs fans, felt this story did not read as if the master had written it. The letters flooded in. The truth was not revealed at the time, but Irwin Porges, in his massive biography of Burroughs, THE MAN WHO CREATED TARZAN, asserts that the story had been written jointly with Burroughs’s son, John Coleman.

Palmer wanted to recapture the fun of the early pulps. He was fortunate in being able to secure three groups of stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs, set respectively in his worlds of Mars, Venus, and Pellucidar. These ran through 1941 and 1942. Although Burroughs’s fortunes had declined in recent years, his name still captured the imagination of old and young alike. The first appearance of an original Burroughs story in AMAZING, however, caused a controversy. The January 1941 issue carried the novelette “John Carter and the Giant of Mars,” but many readers, who were dedicated Burroughs fans, felt this story did not read as if the master had written it. The letters flooded in. The truth was not revealed at the time, but Irwin Porges, in his massive biography of Burroughs, THE MAN WHO CREATED TARZAN, asserts that the story had been written jointly with Burroughs’s son, John Coleman.

Palmer didn’t mind controversy — it helped sell issues. Moreover, ever the Burroughs fan, he favored fiction written in the Burroughs style, and both AMAZING and its companion FANTASTIC ADVENTURES (which Ziff-Davis began to publish with its May 1939 issue) had a strong Burroughsian flavor during the early 1940s. This is especially evident in the work of Ralph Milne Farley and Robert Moore Williams.

Farley had apparently been approached to edit AMAZING STORIES when Ziff-Davis first acquired it in 1938, and had recommended Palmer instead. In the twenties he had written his own Burroughsian-style “Radio Man” series for ARGOSY, set on Venus. The scientist-adventurer of those stories, Miles Cabot, was resurrected in Amazing in “The Radio Man Returns” (June 1939). Stories by Farley, some of them serialized over more than one issue, appeared in eight issues of the magazine during 1939 and 1940.

Williams, who became one of AMAZING‘s most prolific contributors, was a skillful adventure writer, and it is rumored that his Tarzan-like novella “Jongor of Lost Land” changed the fortunes of FANTASTIC ADVENTURES (for the better) after it appeared in that magazine’s October 1940 issue. His initial appearance in AMAZING was with “The Man Who Ruled the World” in June 1938 — the first issue that carried Palmer’s name as editor.

Palmer also used the artistic skills of J. Allen St. John to illustrate the Burroughs stories, as well as several covers, and there is little doubt that all these factors contributed to the continuing growth in AMAZING‘s circulation during the early part of the decade.

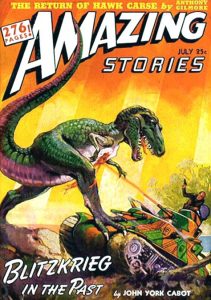

Another echo from the past was “Anthony Gilmore,” the pseudonym under which Harry Bates and Desmond Hall had written their Hawk Carse stories when they were editors of ASTOUNDING. The Hawk Carse stories were space opera at its worst, but they remained sentimentally entrenched in the minds of some fans. Palmer commissioned Bates to write a short novel, “The Return of Hawk Carse” (July 1942). The fact that the story was not well received is at least some measure of the degree by which science fiction had advanced, even at AMAZING‘s juvenile level.

Another echo from the past was “Anthony Gilmore,” the pseudonym under which Harry Bates and Desmond Hall had written their Hawk Carse stories when they were editors of ASTOUNDING. The Hawk Carse stories were space opera at its worst, but they remained sentimentally entrenched in the minds of some fans. Palmer commissioned Bates to write a short novel, “The Return of Hawk Carse” (July 1942). The fact that the story was not well received is at least some measure of the degree by which science fiction had advanced, even at AMAZING‘s juvenile level.

Palmer brought together other writers from the early days of magazine sf, and allowed them free rein with unabashed scientific adventures. Primary among them were Edmond Hamilton, Ross Rocklynne, Manly Wade Wellman, Raymond Z. Gallun, Ed Earl Repp, Stanton A. Coblentz, and Eando Binder. Although they were capable of more serious science fiction (and occasionally proved it in other magazines), they used AMAZING as their knockabout backyard. Stories followed simple plots: they were either gangster stories transposed into space, with villains chasing and being chased around the solar system; or they were war stories in space; or they were tales about bizarre inventions, often with madcap results.

Typical stories of the period by members of this group, which can be generally categorized by their titles alone, include “Treasure on Thunder Moon” by Hamilton (April 1942); “Warrior Queen of Lolarth” by Rocklynne (May 1943); “Suicide-Rocket” by Wellman (March 1942); “Terror out of the Past” by Gallun (March 1940); “The Secret of Planetoid 88” by Repp (December 1941); and “The Cosmic Deflector” by Coblentz (January 1943).

Occasionally, Palmer would acquire fiction from more serious or aspiring writers, including Isaac Asimov, John Beynon (full legal name John Beynon Harris; later known as John Wyndham), and Eric Frank Russell.

“Marooned Off Vesta” (March 1939) was Asimov’s first published story. “The Weapon Too Dreadful to Use” followed in the May 1939 magazine, but Asimov soon became a member of Campbell’s stable at ASTOUNDING and only had one more story in AMAZING during the 1940s (“Robot AL 76 Goes Astray” February 1942).

Beynon’s stories in AMAZING during the early years of Palmer’s tenure were “Judson’s Annihilator” (October 1939, a standard sf war story, and “Phoney Meteor” (March 1941), a clever tale about alien invasion.

Russell’s first appearance in the magazine, and his only one during the decade, was with “Mr. Wisel’s Secret” in February 1942, the same issue that contained the aforementioned Asimov story.

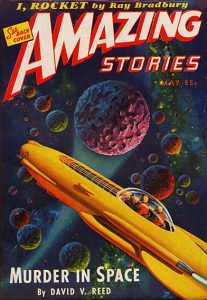

Those were, and are, noteworthy writers, and there were others, but of greatest significance were the stories by Ray Bradbury. Bradbury had an unbridled talent for giving his stories an offbeat originality, something that appealed more to Palmer than to Campbell. His “I, Rocket” (May 1944) is an adventure story from the viewpoint of a sentient rocket, published more than fifteen years before Anne McCaffrey would write “The Ship Who Sang.” Ten years after the appearance of the work, Campbell was still referring to Bradbury’s rocket as his “fairy ship,” since the story was devoid of the hardware for which Campbell yearned. Bradbury was also represented in the magazine by “Undersea Guardians” (December 1944), “Final Victim” (co-credited with Henry Hasse, February 1946), and “Chrysalis” (July 1946).

Those were, and are, noteworthy writers, and there were others, but of greatest significance were the stories by Ray Bradbury. Bradbury had an unbridled talent for giving his stories an offbeat originality, something that appealed more to Palmer than to Campbell. His “I, Rocket” (May 1944) is an adventure story from the viewpoint of a sentient rocket, published more than fifteen years before Anne McCaffrey would write “The Ship Who Sang.” Ten years after the appearance of the work, Campbell was still referring to Bradbury’s rocket as his “fairy ship,” since the story was devoid of the hardware for which Campbell yearned. Bradbury was also represented in the magazine by “Undersea Guardians” (December 1944), “Final Victim” (co-credited with Henry Hasse, February 1946), and “Chrysalis” (July 1946).

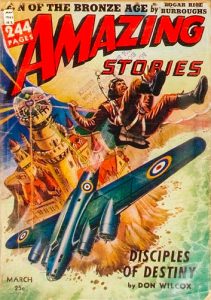

Unfortunately, challenging stories were the exception rather than the rule in AMAZING STORIES at this point in time. By the early 1940s, Palmer had developed a stable of local (Chicago-based) writers who could write to order, often producing stories around cover paintings by Harold McCauley, Robert Gibson Jones, or Malcolm Smith. The mainstays were Don Wilcox, Robert Moore Williams, David Wright O’Brien, William P. McGivern, Leroy Yerxa, and David Vem, plus (later in the decade) Chester S. Geier, Berkeley Livingston, and William L. Hamling.

Of these, Wilcox was the oldest. He approached his writing more seriously than the others, and scored early with a memorable story, “The Voyage That Lasted 600 Years” (October 1940), based on his sociological studies. It was a pioneer work on the subject of the first generation starship.

O’Brien was regarded as the most talented of these writers. A nephew of Farnsworth Wright, editor of WEIRD TALES, he was 22 years old when his first story (“Truth Is a Plague!”) appeared in AMAZING in the February 1940 issue. O’Brien had a fertile mind, an abundance of youthful exuberance, and an infectious sense of humor. He shared an office with McGivern, who was only 16 years old when he made his debut in May 1940 with “John Brown’s Body,” co-written with O’Brien.

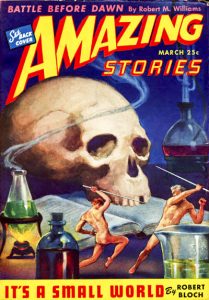

The two of them were able to write just about any story to Palmer’s order. Sometimes the stories were serious, sometimes spooky, but usually they were madcap, designed for nothing but entertainment. Palmer often endowed these stories with his own zany titles, so that the pages of AMAZING STORIES and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES contained stories such as “The Quandary of Quintus Quaggle” (by McGivern, AS June 1941); “Mr. Muddle Does as He Pleases” (McGivern and O’Brien, AS August 1941); “Ferdinand Finknodle’s Perfect Day” (O’Brien, AS September 1941); “The Strange Voyage of Hector Squinch” (O’Brien, FA August 1940); “Sidney, the Screwloose Robot” (McGivern, FA June 1941), and “Rewbarb’s Remarkable Radio” (McGivern, FA December 1941). In many ways the stories of this sort read like P. G. Wodehouse meets AMAZING STORIES, and certainly the readers appreciated this lighthearted fare, which was unavailable elsewhere. Robert Bloch made the best of the situation with a whole series of stories in FANTASTIC ADVENTURES about Lefty Feep, a rather lovable layabout who manages to fall into and out of trouble.

The two of them were able to write just about any story to Palmer’s order. Sometimes the stories were serious, sometimes spooky, but usually they were madcap, designed for nothing but entertainment. Palmer often endowed these stories with his own zany titles, so that the pages of AMAZING STORIES and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES contained stories such as “The Quandary of Quintus Quaggle” (by McGivern, AS June 1941); “Mr. Muddle Does as He Pleases” (McGivern and O’Brien, AS August 1941); “Ferdinand Finknodle’s Perfect Day” (O’Brien, AS September 1941); “The Strange Voyage of Hector Squinch” (O’Brien, FA August 1940); “Sidney, the Screwloose Robot” (McGivern, FA June 1941), and “Rewbarb’s Remarkable Radio” (McGivern, FA December 1941). In many ways the stories of this sort read like P. G. Wodehouse meets AMAZING STORIES, and certainly the readers appreciated this lighthearted fare, which was unavailable elsewhere. Robert Bloch made the best of the situation with a whole series of stories in FANTASTIC ADVENTURES about Lefty Feep, a rather lovable layabout who manages to fall into and out of trouble.

Although forgotten today, Leroy Yerxa was among the most prolific contributors to the Ziff-Davis magazines. He was twenty-seven years old when his first story, “Death Rides at Night” appeared under his own name in the August 1942 AMAZING. In the next four years, till his untimely death in 1946, he sold more than seventy stories to Palmer for AMAZING STORIES and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES, with many of those published pseudonymously. He is rumored to have written an entire issue of FANTASTIC ADVENTURES (possibly the one for December 1943). While other writers wrote more, their output was not concentrated in such a short, intense period. Possibly Yerxa’s only rival in this regard was David Wright O’Brien, who in the five years from 1940 through 1944 sold more than a hundred stories to Palmer, not counting his collaborations with McGivern.

Palmer’s core of writers were so prolific that they could fill every issue. To avoid the frequent recurrence of names, the authors used various personal pseudonyms, some of which were later adopted by other authors. For instance, “Lee Francis” began as a pen name of Leroy Yerxa’s, but after his death in 1946 it was used by others, including Hamling. In addition, a practice began of creating a number of house names. These nom de plumes were originally used to hide the identities of the various editorial personnel working on the magazine, especially David Vern.

Vern was a precocious, hyperactive young editorial assistant who came from New York to the Chicago office to help Palmer with the work arising from the expansion of the magazine line. (In addition to AMAZING STORIES and its new companion FANTASTIC ADVENTURES, Palmer was also editing RED STAR ADVENTURES and SOUTH SEA STORIES.)

Vern was also a passable writer, and his work started to appear in both magazines under the names of “Peter Horn,” “David V. Reed,” and “Alexander Blade.” (His first contribution to AMAZING was “Where Is Roger Davis?” in the May 1939 issue under the “Reed” pseudonym.) However, when Vern returned to New York after a few years these names, particularly “Alexander Blade,” were assigned to a variety of other writers.

Other house names emerged, including “P. F. Costello,” “Gerald Vance,” “E. K. Jarvis,” and “S. M. Tenneshaw” — originally used by McGivern, O’Brien, Williams, and Hamling, respectively. O’Brien also wrote as “John York Cabot” and (perhaps in homage to his uncle) “Duncan Farnsworth.” Palmer himself produced more than a dozen pieces of writing for AMAZING during the 1940s, using a variety of pseudonyms including “A. R. Steber,” “Morris J. Steele,” “Frank Patton,” “Henry Gade,” “Wallace Quitman,” and “G. H. Irwin.” Clearly, at times it could be difficult to tell the players even with a scorecard. Despite the efforts of a number of researchers over the years, many of the true authors of house name stories remain unidentified (although work that Kenneth R. Johnson is currently doing is close to cracking open the final parts of the mystery). (It is not known if Johnson ever solved “the final parts of the mystery.” However, since Johnson’s research into the subject has, to our knowledge, never been released, it seems unlikely that he did so.)

Other house names emerged, including “P. F. Costello,” “Gerald Vance,” “E. K. Jarvis,” and “S. M. Tenneshaw” — originally used by McGivern, O’Brien, Williams, and Hamling, respectively. O’Brien also wrote as “John York Cabot” and (perhaps in homage to his uncle) “Duncan Farnsworth.” Palmer himself produced more than a dozen pieces of writing for AMAZING during the 1940s, using a variety of pseudonyms including “A. R. Steber,” “Morris J. Steele,” “Frank Patton,” “Henry Gade,” “Wallace Quitman,” and “G. H. Irwin.” Clearly, at times it could be difficult to tell the players even with a scorecard. Despite the efforts of a number of researchers over the years, many of the true authors of house name stories remain unidentified (although work that Kenneth R. Johnson is currently doing is close to cracking open the final parts of the mystery). (It is not known if Johnson ever solved “the final parts of the mystery.” However, since Johnson’s research into the subject has, to our knowledge, never been released, it seems unlikely that he did so.)

A strong family atmosphere prevailed in the Ziff-Davis offices in Chicago during this period, with Palmer looking after his boys. Wilcox, who is still active after all these years (Wilcox remained active until his death in the year 2000) though more now as a portrait painter than as a writer, has shared many memories of those days with me. “A card game, usually gin rummy, would be occupying the attention of editors and their assistants,” he recalled. “The fellows must have done their work at night. On check days, Palmer’s office might be a gathering place for several new writers, new faces, all ready to register disappointment if the checks hadn’t come in on time.”

Palmer had a fast-working, versatile mind. Wilcox has a clear memory of him furiously pounding his typewriter at high speed. On one occasion Wilcox had become too deeply involved in his story “The Lost Race Comes Back,” written around a cover painting by J. Allen St. John, and couldn’t finish it. Palmer promptly read the story and completed it himself there and then to meet the deadline. (The story appears in the May 1941 issue.)

The outward signs of AMAZING‘s success were its regularity — published once a month for five years beginning in November 1938 — and an increased number of pages. During 1941 and 1942 the page count rose from 144 up to 240 and all the way to 272. Even after the onset of World War II and the subsequent paper rationing, the magazine kept to 208 pages for a time (later shrinking to 180), remaining constantly the best value in bulk for money. But as war rationing continued to bite into the publishing industry, AMAZING was forced to cut back on its production schedule. In late 1943 the magazine shifted to bimonthly, and then to quarterly after the following summer, not returning to monthly publication until the June 1946 issue.

Palmer supported the war effort by publishing the largest quota of anti-Nazi propagandist fiction of any sf magazine. Much of it made fun of the German war effort, but some stories were serious in tone. Palmer contributed a number himself, such as “A Patriot Never Dies” (August 1943) and “War Worker 17” (September 1943), both under his “Frank Patton” alias. The latter appeared in an issue dedicated to women war workers. The September 1944 magazine was a special war issue; every story in it was identified as having been written by a member of the military, and it also contained letters from the troops.

Palmer supported the war effort by publishing the largest quota of anti-Nazi propagandist fiction of any sf magazine. Much of it made fun of the German war effort, but some stories were serious in tone. Palmer contributed a number himself, such as “A Patriot Never Dies” (August 1943) and “War Worker 17” (September 1943), both under his “Frank Patton” alias. The latter appeared in an issue dedicated to women war workers. The September 1944 magazine was a special war issue; every story in it was identified as having been written by a member of the military, and it also contained letters from the troops.

The most significant contributor to that issue was Corporal David Wright O’Brien, with three stories — one under his real name and one each attributed to “Corporal John York Cabot” and “Corporal Duncan Farnsworth.” The AMAZING office was shocked when O’Brien, who served in the U. S. Air Force, was shot down and killed over Berlin later that year at the age of twenty-six. He had been a personable, friendly young man with an effervescent writing talent, and there is no doubt that he would have followed his close friend William McGivern into the big time if he had survived the war.

During the war years, Ziff-Davis began publishing two new mystery magazines, MAMMOTH DETECTIVE, which started in May 1942, and MAMMOTH MYSTERY, which came out in February 1945. (These magazines gave McGivern the grounding that later helped to establish him as one of the top thriller writers.) To help Palmer edit these new titles, Bernard Davis brought in 34-year-old Howard Browne, a solid, no-nonsense detective writer of the Chandler school.

Browne had no interest in science fiction, though he enjoyed the fantasies in FANTASTIC ADVENTURES. Ironically, however, his first appearance as a writer was in AMAZING. Palmer talked Browne into writing a novel set in prehistoric times, “Warrior of the Dawn,” which was serialized in late 1942 and early 1943. Adventures in prehistory, usually written in the Burroughsian style, were regular fare in both AMAZING and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES during the early years of Palmer’s tenure as editor. Among the most popular offerings were Manly Wade Wellman’s series of stories about Hok, a Stone Age warrior who was a prototype for Hercules. Hok fought his way through five adventures, including ones set in ancient Greece and Atlantis.

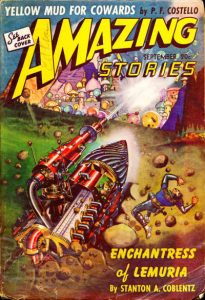

The lost continents of Atlantis, Lemuria, and Mu all figured prominently in both magazines. For instance, “Adventure in Lemuria” by Frederic Arnold Kummer, Jr., appeared in the first issue of FANTASTIC ADVENTURES (May 1939), and was followed by several sequels. Stanton A. Coblentz’s “Enchantress of Lemuria” was the lead novel in the September 1941 issue of AMAZING. In addition, in that same issue L. Taylor Hansen began a column on scientific mysteries, which dealt with Gondwanaland, Atlantis, and other puzzles from before the dawn of science.

The lost continents of Atlantis, Lemuria, and Mu all figured prominently in both magazines. For instance, “Adventure in Lemuria” by Frederic Arnold Kummer, Jr., appeared in the first issue of FANTASTIC ADVENTURES (May 1939), and was followed by several sequels. Stanton A. Coblentz’s “Enchantress of Lemuria” was the lead novel in the September 1941 issue of AMAZING. In addition, in that same issue L. Taylor Hansen began a column on scientific mysteries, which dealt with Gondwanaland, Atlantis, and other puzzles from before the dawn of science.

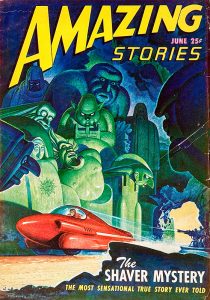

Thus, readers of AMAZING became accustomed to Palmer’s fascination with ancient mysteries, and when Richard S. Shaver appeared in the March 1945 issue with a piece entitled “I Remember Lemuria,” the story should have come as no surprise. Nor would it have — except that Palmer claimed the story was based on truth!

Shaver maintained that eons ago, the earth had been inhabited by two super-races, the Titans and the Atlans. As time passed, they were forced underground by increasingly harmful radiation from the sun. They established vast subterranean caverns full of advanced scientific equipment. Eventually the sun’s radiation became too harmful, and both races were forced to abandon the planet. They left their scientific equipment behind, and it was later discovered by an inferior race of humans who tampered with the machinery and came under its control. Over the millennia these humans degenerated into deranged robots, or, in Shaver-speak, “deros.” It is the harmful rays and evil thoughts generated from the machines by these deros that have caused mankind to fall from grace, and are the cause of all of humanity’s ills. With the world in the grips of a war that was entering its final months, such a message, if indeed it were true, came as a sign of hope to many readers. If all evils came from external influences, then they could be stopped, and mankind would revert to its natural good state, and all would be well!

The origin of the Shaver stories has at times seemed confusing, though Palmer reported it himself clearly on many occasions, and Howard Browne had a vivid recollection of the events. Some years ago Browne recounted his memories to me: Shaver had submitted a two-page letter to AMAZING under the heading “Warning to Future Man.” Browne was the first one to read it. He remarked to Palmer that “the screwballs were blooming early” that year, and tossed the manuscript into the wastebasket. Palmer promptly retrieved it and said to Browne, “Let me give you a lesson in creative editing.” He thereupon sat down, read the manuscript, and wrote a novelette around it — the piece of writing that was published as “I Remember Lemuria.” Palmer then discovered Shaver had several longer stories in his possession. Palmer bought them, rewrote them extensively, and published them. As time went on, under Palmer’s guidance, Shaver wrote more and more stories himself, but the initial ones were shaped and crafted by Palmer.

Prior to the appearance of the Shaver stories, AMAZING was selling around 125,000 copies per issue. The March 1945 issue had a larger than normal print run — and it soon sold out. Letters from readers poured in, and with the next issue, featuring Shaver’s “Thought Records of Lemuria,” circulation approached 200,000. Palmer’s employees were impressed, and Palmer overtly promoted the Shaver Mystery for all it was worth. There was a Shaver story in almost every issue for the next two years, culminating in an all-Shaver issue for June 1947. Other writers also contributed stories in the same vein, including Chester Geier, who founded the Shaver Mystery Club, and German writer Heinrich Hauser, then living in Chicago, who added two linked novels, “Agharti” (June 1946) and “Titans’ Battle” (March 1947).

Prior to the appearance of the Shaver stories, AMAZING was selling around 125,000 copies per issue. The March 1945 issue had a larger than normal print run — and it soon sold out. Letters from readers poured in, and with the next issue, featuring Shaver’s “Thought Records of Lemuria,” circulation approached 200,000. Palmer’s employees were impressed, and Palmer overtly promoted the Shaver Mystery for all it was worth. There was a Shaver story in almost every issue for the next two years, culminating in an all-Shaver issue for June 1947. Other writers also contributed stories in the same vein, including Chester Geier, who founded the Shaver Mystery Club, and German writer Heinrich Hauser, then living in Chicago, who added two linked novels, “Agharti” (June 1946) and “Titans’ Battle” (March 1947).

It is not clear how much Palmer was milking the gullible, as any entrepreneur might. He left mixed messages over the years. In all likelihood Palmer, the victim of many handicaps and misfortunes, wanted to believe it, and was prepared to go along with it all the time it sustained sales.

Shaver was certainly sincere. When I corresponded with him in the 1970s, he still maintained the truth of his experiences and observations. By then he was pursuing ancient records in the rocks, where he believed the true history of Atlan was written.

Science fiction fans were less enthusiastic, and they became hostile to AMAZING‘s editor. Palmer, who only ten years earlier had been one of the leading sf fans, attempted some reconciliation by instigating a fan column in the March 1948 issue, “The Club House,” prepared by Rog Phillips. But on the whole, the sf fans formed only a small part of the readership of AMAZING, and if they had to be antagonized for the sake of sales, why should Palmer worry?

Eventually such leading magazines as HARPER’S and ATLANTIC MONTHLY began to notice and criticize the crackpot elements of the Shaver Mystery, and the story goes (according to him) that Palmer was told to soft-pedal the topic thereafter. Whether that is true or not, I don’t know, since it would seem surprising for a publisher to act negatively in reaction to such publicity. (One learns never to take too seriously anything Palmer says.) The fact remains that by the end of 1946, Davis had been elevated within the company, and Ray Palmer followed him up the ladder to become overall editorial director. He was given a salary increase of around $250 a month and even more freedom with the magazines.

Palmer’s next move, though, was rather devious. During 1947, he shut down MAMMOTH DETECTIVE, MAMMOTH MYSTERY, and the recently created MAMMOTH ADVENTURES. He placed William Hamling in editorial control of the two magazines — AMAZING STORIES and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES — while Howard Browne took a leave of absence during which he wrote three mystery novels.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Palmer invested his money in establishing the Clark Publishing Company and, in May 1948, launched the magazine FATE. Robert N. Webster (an alias of Palmer’s) was identified as the publisher of the new magazine.

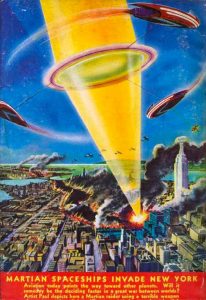

Palmer had come to realize that much wealth lay in appealing to the fringe cults. Following the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world had not only awoken to the terrifying consequences of science, but also to other possibilities. One such was that man’s advance into the nuclear age had been the sign to alien observers that man was becoming a danger to himself and his planet, and he had to be kept under closer observation. Hence, the sudden wave of flying saucer sightings. Palmer had been one of the first to promote “ufology” in the pages of AMAZING. Now he could use FATE as he wished to pander to all of the occult sciences. As a consequence, that type of material was siphoned from AMAZING to FATE.

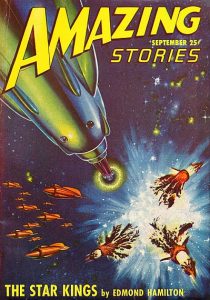

With that shift, the quality of fiction in AMAZING improved marginally. Theodore Sturgeon put in a surprise appearance with “Blabbermouth” (February 1947), a story probably switched from the inventory of FANTASTIC ADVENTURES. Edmond Hamilton, ever an old reliable, who during the early 1940s had scored with his Captain Future stories in the magazine of the same name, wrote “The Star Kings” (September 1947), a space opera par excellence, again in the Burroughs tradition. There were also some readable, non-Shaverian stories from Rog Phillips, Chester Geier, and Don Wilcox, but by and large the mid to late 1940s saw AMAZING at its lowest point in quality — yet its highest in circulation!

With that shift, the quality of fiction in AMAZING improved marginally. Theodore Sturgeon put in a surprise appearance with “Blabbermouth” (February 1947), a story probably switched from the inventory of FANTASTIC ADVENTURES. Edmond Hamilton, ever an old reliable, who during the early 1940s had scored with his Captain Future stories in the magazine of the same name, wrote “The Star Kings” (September 1947), a space opera par excellence, again in the Burroughs tradition. There were also some readable, non-Shaverian stories from Rog Phillips, Chester Geier, and Don Wilcox, but by and large the mid to late 1940s saw AMAZING at its lowest point in quality — yet its highest in circulation!

Palmer’s link with the magazine grew more tenuous as FATE became more popular. By mid-1949 his plans were well advanced for a new science-fiction magazine, OTHER WORLDS, which appeared in October (cover date November). Palmer continued to produce both FATE and OTHER WORLDS under the Webster alias until he was satisfied that both magazines were established. He then resigned from Ziff-Davis, and Howard Browne came back from his leave of absence to take over editorial control of the magazines, with Hamling staying on as his assistant. The January 1950 issue was the first one to list Browne as editor.

Browne may not have liked science fiction very much, but he knew a good story when he saw one, and was dedicated to acting responsibly in his new role. The end of 1949 saw him discarding several hundred thousand words of Shaver-inspired material, as he sought to re-establish the magazine’s credibility. His successes and failures make up the next part of “The AMAZING Story.”

“The AMAZING Story: The Forties — ‘Gimme Bang-Bang'” is © 2016 by Mike Ashley and appears here with the author’s permission. Notes in italics are by PulpFest and are © 2016 by PulpFest. The original article was published by TSR, Inc. and edited by Kim Mohan for the March 1992 issue of AMAZING STORIES.Many thanks to Curt Phillips, the moderator of the Yahoo newsgroup PulpMags, for drawing our attention to and providing us with copies of Mike Ashley’s exceptional series of articles about the world’s first science-fiction magazine. Please visit pulpcon.org on Monday, February 29th, for the fourth segment of the series.

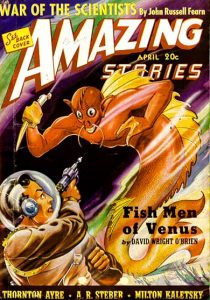

(Concerning our illustrations . . . . The AMAZING STORIES for April 1940 with cover art by H. R. Hammond — the artist’s only cover for the magazine — was a typical issue for the decade. When Ray Palmer was named managing editor in 1938, he established a new policy for lively, adventurous stories aimed at a young market. He wanted superficial, escapist enjoyment, similar to the scientific romances that the pulp magazines had once published, but less sophisticated. David Wright O’Brien’s “Fish Men of Venus” was the usual fare for the Palmer era of the magazine.

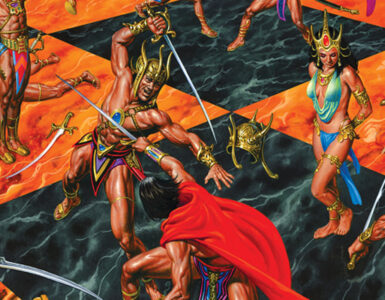

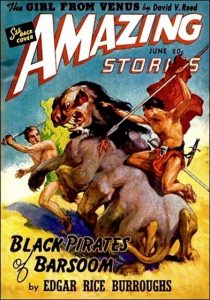

During the early forties, Palmer was fortunate in being able to secure three groups of stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs, set respectively in his worlds of Mars, Venus, and Pellucidar. The six Martian stories that Burroughs sold to AMAZING STORIES — including “Black Pirates of Barsoom,” published in the June 1941 issue of AMAZING STORIES with front cover art by J. Allen St. John — formed the basis for the author’s final two books in his Mars series — LLANA OF GATHOL and JOHN CARTER OF MARS.

One of the finest artists to contribute cover art to Ray Palmer’s AMAZING STORIES was J. Allen St. John. A native of Chicago — where AMAZING STORIES was produced — he began to work for various Midwestern publishers — including the A. C. McClurg Company of Chicago — in the early 1900s. In 1915 he illustrated chapter headings for Edgar Rice Burroughs’ THE RETURN OF TARZAN, published by McClurg. Thus began the artist’s long association with Burroughs, the work for which he is most renowned. St. John also painted the front cover art for the July 1942 issue of AMAZING STORIES, featuring “The Return of Hawk Carse.”

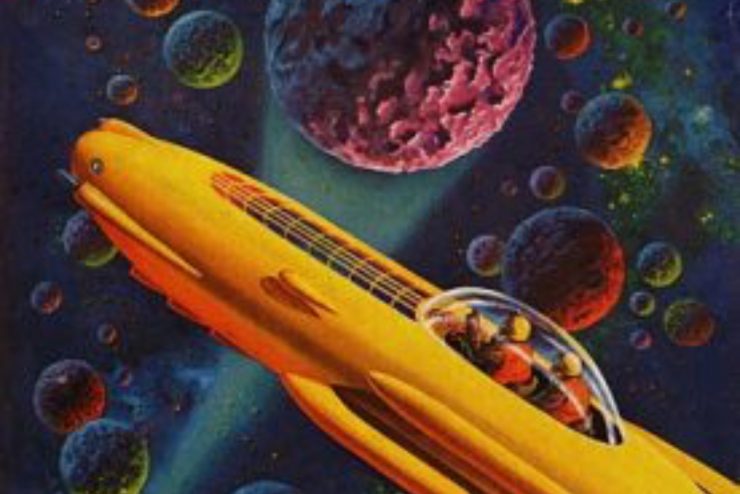

The May 1944 AMAZING STORIES — with front cover art by Malcolm Smith — featured what John W. Campbell labeled Ray Bradbury’s “fairy ship,” in “I, Rocket,” the classic tale related from the viewpoint of a sentient space ship. A native of Tennessee, Smith studied at the American Academy of Art in Chicago. His first cover for AMAZING was the January 1942 number. Smith also contributed covers and illustrations to FANTASTIC ADVENTURES and Ziff-Davis’s MAMMOTH line of pulp magazines. During the fifties, he produced covers for IMAGINATION, MYSTIC, OTHER WORLDS, and other pulp and digest magazines.

J. Allen St. John began contributing cover art to the pulps during the Great Depression, painting covers for WEIRD TALES and its companions — ORIENTAL STORIES and THE MAGIC CARPET. During the 1940s, he contributed two dozen covers to Ray Palmer’s AMAZING STORIES and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES, including the March 1944 issue of AMAZING.

Ray Palmer was one of the leading science fiction fans when he became the managing editor of AMAZING STORIES. In order to attract other members of fandom to his magazine, Palmer added such features as “Correspondence Corner,” “Collectors’ Corner,” “Meet the Authors,” and a back cover painting. Many of the latter featured the work of Frank R. Paul, including the May 1941 issue. Frank Paul was the artist most preferred by Hugo Gernsback during the early years of AMAZING STORIES.

Joseph Wirt Tillotson, who signed his work “Robert Fuqua,” was managing editor Ray Palmer’s favored cover artist from the get-go. Beginning with the October 1938 issue of AMAZING STORIES through the January 1944 number, Fuqua contributed nearly three-dozen covers — including the March 1942 and September 1941 issues — to the magazine and its companion title, FANTASTIC ADVENTURES.

A native of Toledo, Ohio, Robert Gibson Jones began working as a commercial artist in the city of Chicago during the second decade of the twentieth century. His first known pulp magazine cover was the August 1942 issue of Ziff Davis’s FANTASTIC ADVENTURES. Over the next ten years, Jones contributed ninety front covers to FANTASTIC and its companion, AMAZING STORIES, including the June 1947 number. He also painted covers for the publisher’s MAMMOTH line of pulp magazines. His last known cover for the publisher is the December 1952 issue of FANTASTIC ADVENTURES. During the fifties, he contributed covers to OTHER WORLDS and UNIVERSE SCIENCE FICTION.

The September 1947 AMAZING STORIES — with front cover art by Malcolm Smith — featured one of the best of the space opera novels from the pulps, Edmond Hamilton’s “The Star Kings.” It has been reprinted numerous times.)