AMAZING — From Howard Browne to Paul Fairman

The garbage cans at the Ziff-Davis offices must have been full at the close of 1949. It was then that Howard Browne took over from Ray Palmer as editor-in-chief of the Ziff-Davis fiction magazines. He disposed of 300,000 words of purchased manuscripts, clearing the decks of the Shaver-inspired material that had haunted AMAZING STORIES and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES during the last five years. Browne had a free hand under publisher Bernard Davis to make the magazines respectable.

The garbage cans at the Ziff-Davis offices must have been full at the close of 1949. It was then that Howard Browne took over from Ray Palmer as editor-in-chief of the Ziff-Davis fiction magazines. He disposed of 300,000 words of purchased manuscripts, clearing the decks of the Shaver-inspired material that had haunted AMAZING STORIES and FANTASTIC ADVENTURES during the last five years. Browne had a free hand under publisher Bernard Davis to make the magazines respectable.

L. Sprague de Camp, writing in his SCIENCE-FICTION HANDBOOK in 1953, described Browne as “a huge massive man with a bone-crushing handclasp and, like Palmer, a keen commercial sense.” It was Browne’s desire to convert AMAZING into an up-market glossy magazine. He was of the view that the days of the pulp magazine were over. Since the world had become aware of the devastating power of the nuclear bomb, science fiction had come of age, and had earned a small respectability among the higher-class magazines. Several sf writers from the pulps, including Robert A. Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, and Murray Leinster, were now selling regularly to up-market magazines such as COLLIER’S and THE SATURDAY EVENING POST, and Browne believed there was a space in that market for an all science-fiction magazine.

It meant paying good money. He raised the promised payment rates, previously only about one cent a word, to five cents. He made the rounds of the leading literary agents seeking quality stories, and secured promises from Isaac Asimov, Theodore Sturgeon, Fritz Leiber, Clifford Simak, and other major names. By April 1950 he was ready to put together a dummy issue (which has since become a collector’s item) — and then the axe fell.

In June 1950 the North Koreans invaded South Korea. With the American economy suddenly redirected toward combating the invasion, budgets were cut and the gamble of a slick AMAZING was dropped as too risky. The stories Browne had purchased made their way into the pulp pages of AMAZING, among them “Operation R. S. V. P.” by H. Beam Piper and “Satisfaction Guaranteed” by Isaac Asimov. The news of Browne’s plans had caused other agents to reconsider AMAZING as a market, and this had brought in stories from other big names — Fritz Leiber, William F. Temple, Fredric Brown, Clifford Simak — so that by the end of 1950 there was a glimmer of quality about AMAZING that had not been evident for many years.

A sure sign of an improving market is when a magazine begins to encourage and foster new writers — the lifeblood which enables science fiction to develop. Rapidly, under Browne’s editorship, the stable of Ziff-Davis writers (Rog Phillips, Berkeley Livingston, Don Wilcox, Chester Geier) found itself being nudged aside by talented newcomers. John W. Jakes, better known these days for his NORTH AND SOUTH Civil War novels, made his first sale to Howard Browne in 1950. (“Your Number Is Up!” was in the December issue.) Other members of the vanguard of new talent included Mack Reynolds, whose first sale to AMAZING was “United We Stand” (May 1950); Milton Lesser (known today as historical writer Stephen Marlowe), who debuted in November 1950 with “All Heroes Are Hated!”; Charles Beaumont, who contributed “The Devil, You Say?” in January 1951; and Walter M. Miller, Jr., whose first professional sale was “Secret of the Death Dome” (January 1951). All four of these men were destined to become leading sf writers of the 1950s.

A sure sign of an improving market is when a magazine begins to encourage and foster new writers — the lifeblood which enables science fiction to develop. Rapidly, under Browne’s editorship, the stable of Ziff-Davis writers (Rog Phillips, Berkeley Livingston, Don Wilcox, Chester Geier) found itself being nudged aside by talented newcomers. John W. Jakes, better known these days for his NORTH AND SOUTH Civil War novels, made his first sale to Howard Browne in 1950. (“Your Number Is Up!” was in the December issue.) Other members of the vanguard of new talent included Mack Reynolds, whose first sale to AMAZING was “United We Stand” (May 1950); Milton Lesser (known today as historical writer Stephen Marlowe), who debuted in November 1950 with “All Heroes Are Hated!”; Charles Beaumont, who contributed “The Devil, You Say?” in January 1951; and Walter M. Miller, Jr., whose first professional sale was “Secret of the Death Dome” (January 1951). All four of these men were destined to become leading sf writers of the 1950s.

A final break with the old era came at the close of 1950, when Ziff-Davis decided to move its editorial offices to New York. (The production side of the operation remained in Chicago.) Browne was quite happy with the move, as was his associate editor Lila Shaffer, but William Hamling, who had done the bulk of the editorial work since Palmer began to phase himself out in 1948, was less enthusiastic; he had too many connections in Chicago. So Hamling followed in Palmer’s footsteps and established his own publishing company, called Greenleaf. Hamling took over publication of IMAGINATION, a magazine started for him by Palmer. He later moved into the market for men’s magazines with the highly successful ROGUE.

The move to New York was completed by early 1951. It meant that the members of the old stable of Chicago writers were no longer regulars in the magazine, and Browne was able to secure stories from a wider range of writers via direct contact with the New York agencies. However, the benefits of this changeover took some time to materialize.

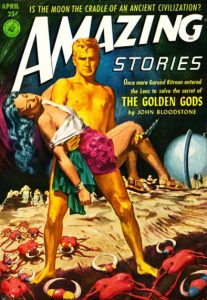

Lila Shaffer had now taken over as managing editor under Browne’s overall control. Browne had every confidence in her, regarding her as highly competent and an excellent editor. But, like Browne, she had little knowledge of or interest in science fiction. FANTASTIC ADVENTURES fared better for material of reasonable quality than did AMAZING, primarily because of the editor’s greater interest in fantasy fiction. Once the backlog of “slick” stories was used up, AMAZING reverted to the routine space-adventure magazine it had been in the 1940s. Typical of its contents was the Michael Flannigan trilogy: “The Land Beyond the Lens,” “The Golden Gods,” and “The Return of Michael Flannigan.” These stories were written by Stuart J. Byrne under the alias of John Bloodstone, in the style of Edgar Rice Burroughs. The series, which ran in the March, April, and August 1952 issues, pitched Flannigan into another world where he became a superhero fighting against astonishing odds. Nothing new there. In fact, as an aside, it’s a sad reflection that most fantastic fiction written today isn’t far advanced from that, yet remains equally popular.

Overall, 1952 was not a good year for the kind of image Browne had hoped to engender. Too often the stories, through their titles, continued to project the old pulp style of adventure, such as in Don Wilcox’s “The Mad Monster of Mogo” (November 1952) or Milton Lesser’s “Secret of the Black Planet” (June 1952). Even though most of the stories weren’t too bad, they still projected the feeling that AMAZING was a Burroughs-inspired magazine. In fact, some readers regarded Browne as a Burroughs-style writer and suspected the Bloodstone stories were his work. There was an image about the magazine that was impossible to overcome in the pulp format.

Overall, 1952 was not a good year for the kind of image Browne had hoped to engender. Too often the stories, through their titles, continued to project the old pulp style of adventure, such as in Don Wilcox’s “The Mad Monster of Mogo” (November 1952) or Milton Lesser’s “Secret of the Black Planet” (June 1952). Even though most of the stories weren’t too bad, they still projected the feeling that AMAZING was a Burroughs-inspired magazine. In fact, some readers regarded Browne as a Burroughs-style writer and suspected the Bloodstone stories were his work. There was an image about the magazine that was impossible to overcome in the pulp format.

There was also the astonishing inclusion of a series of works I’m surprised Browne condoned. These were the “Master of the Universe” stories, which ran from April through November 1952 and were credited to “Author Unknown” (or, in the last two installments, “Author Unborn”). The series purported to be a manuscript giving the future history of Earth from 1975 to 2575, complete with serious footnotes and references to future sources. Like the Shaver Mystery, it was presented as fact, and it created a modicum of reaction from readers — some of whom asked for copies of the future books! One of the footnotes in the series refers to a book by John Evans, which was a pen name of Browne’s. Some years ago I wondered whether Browne had written this series, as a retaliation to the budget cuts and so as a way of expressing his frustrations at not being able to develop the magazines. When I put this question to him in 1982, he had no recollection of the series. I am still unsure who did perpetrate it, and would be interested to hear from anyone who might know. The series did nothing to further the image of AMAZING STORIES.

By 1952 science fiction was undergoing a surge of popularity in the United States. Scores of new science-fiction magazines had appeared in the last few years or were now appearing, and two of the newest — GALAXY, edited by Horace L. Gold, and THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION, edited by Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas, were vying with ASTOUNDING for honors as the leading sf magazine. Indeed, these titles were already known as “The Big Three.” GALAXY was closest to the image that Browne had wanted. Gold selected a more sophisticated style of science fiction — not hung up on technology, as ASTOUNDING so often was, but concentrating on the human angle.

Ever since 1943, ASTOUNDING had been published in a small pulp format, only a little larger than the digest size that had become established among literary magazines and reviews. When THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY (as it was initially called) appeared in October 1949, it also followed the digest format, as did GALAXY a year later. The day of the pulp magazine was passing into history. Many of the young readers whom the pulps had attracted were switching to comic books, while older readers were turning to the rapidly growing market in paperback books. Television was also just starting to make its mark, and some of the old-guard pulp writers were finding it more lucrative to continue their trade writing for television.

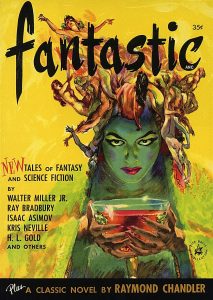

All of this meant that by 1952 a major change was happening in the magazine market, though many publishers were unsure what direction to take. Ziff-Davis thought it would test the waters of the digest-magazine market, and this gave Browne a second opportunity to create his dream magazine. Since his heart was in fantasy rather than sf, Browne opted to launch a new fantasy magazine called, simply, FANTASTIC. Unlike the slick magazines, which required significant advertising revenue to sustain their high-quality production, the digest magazines were only pulps in reduced format, and Ziff-Davis was therefore able to invest money in increasing word rates. FANTASTIC promised up to ten cents a word for leading writers. It also sought to go up-market by including two-tone color interior artwork, as well as wraparound covers.

The first issue of FANTASTIC, dated Summer 1952, appeared on March 21, and is a beautiful issue to behold, even now. A delicious cover by Barye Phillips, depicting a witch, heralded a collection of stories by top writers, including Raymond Chandler, with a little-known story reprinted from PARK EAST MAGAZINE, “Professor Bingo’s Snuff.” Other writers included Walter M. Miller, Kris Neville, Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, and Horace Gold. The writing was sharp and sophisticated, a long way from that appearing in FANTASTIC ADVENTURES or AMAZING STORIES. Some readers criticized that the magazine’s quality was not as high as had been expected, but it was on a par with F&SF, and showed much promise for the future.

The first issue of FANTASTIC, dated Summer 1952, appeared on March 21, and is a beautiful issue to behold, even now. A delicious cover by Barye Phillips, depicting a witch, heralded a collection of stories by top writers, including Raymond Chandler, with a little-known story reprinted from PARK EAST MAGAZINE, “Professor Bingo’s Snuff.” Other writers included Walter M. Miller, Kris Neville, Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, and Horace Gold. The writing was sharp and sophisticated, a long way from that appearing in FANTASTIC ADVENTURES or AMAZING STORIES. Some readers criticized that the magazine’s quality was not as high as had been expected, but it was on a par with F&SF, and showed much promise for the future.

Soon after the second issue had appeared in June, FANTASTIC shifted to a bimonthly schedule. The third issue, which boasted a Mickey Spillane novelette, “The Veiled Woman,” allegedly sold 90 percent of its print run, which was almost unheard of in publishing circles. (The May 1984 issue of AMAZING STORIES contains a fascinating article by Howard Browne, in which he talks about his experiences as editor and also offers an interesting insight into the true story behind “The Veiled Woman” and how it came to be written.)

Ziff-Davis was satisfied. Browne was given a $200-a-month raise and the go-ahead to convert AMAZING STORIES to a digest magazine. He was also given the budget to employ a new editorial assistant. Browne selected Paul W. Fairman, a versatile thirty-six-year-old writer he had discovered two years earlier. Fairman had become a prolific contributor to the Ziff-Davis pulps under a variety of pen names, the most notorious being “Ivar Jorgensen.” Over the last year Fairman had been actively involved in launching a new magazine, IF, the same magazine that became GALAXY‘s companion in the 1960s and won a bunch of Hugo Awards. Soon after his appointment, Fairman replaced Lila Shaffer as managing editor when she left Ziff-Davis to marry.

By early 1953, FANTASTIC ADVENTURES had merged with FANTASTIC and, after its March 1953 issue, AMAZING STORIES became a digest and shifted from a monthly to a bimonthly schedule. That shift in frequency of publication came as something of a shock to readers, and it suggests that Ziff-Davis was still not wholly confident about the format change. The money the company was plowing into the two titles in production costs and enhanced word rates had to be balanced somehow, and one way to reduce the financial outlay was to put out fewer issues over a given span of time.

Nevertheless, Browne pulled out the stops editorially. Despite his lack of interest in science fiction, he now tightly held the editorial reins, personally selecting all the stories for AMAZING and FANTASTIC. The first digest-sized AMAZING included stories from Robert Heinlein (“Project Nightmare”), Theodore Sturgeon (“The Way Home”), Richard Matheson (“The Last Day”), Murray Leinster (“The Invaders”), and Ray Bradbury (“Here There Be Tygers”). It had a feel of sophistication about it, at least when compared to the previous pulp issues, though the initial impact came from the pen-and-ink illustrations rather than the stories. Art editor Leo Ramon Summers, together with artists Robert Kay, Charles Berger, David Stone, and Henry Sharp, had gone for an economical spidery style that reflected simple carefree imagery rather than scientific detail or sense-of-wonder action. Only Ed Emshwiller and Virgil Finlay retained their usual styles.

Nevertheless, Browne pulled out the stops editorially. Despite his lack of interest in science fiction, he now tightly held the editorial reins, personally selecting all the stories for AMAZING and FANTASTIC. The first digest-sized AMAZING included stories from Robert Heinlein (“Project Nightmare”), Theodore Sturgeon (“The Way Home”), Richard Matheson (“The Last Day”), Murray Leinster (“The Invaders”), and Ray Bradbury (“Here There Be Tygers”). It had a feel of sophistication about it, at least when compared to the previous pulp issues, though the initial impact came from the pen-and-ink illustrations rather than the stories. Art editor Leo Ramon Summers, together with artists Robert Kay, Charles Berger, David Stone, and Henry Sharp, had gone for an economical spidery style that reflected simple carefree imagery rather than scientific detail or sense-of-wonder action. Only Ed Emshwiller and Virgil Finlay retained their usual styles.

The magazine was a critical success, and was welcomed by the more serious reader, but it was a giant leap for the average pulp-adventure fan for whom AMAZING had served as a monthly ticket to the planets. Overnight, AMAZING had changed its market and was trying to attract a new one. This strategy might have worked in less competitive times, but with the scores of magazines then vying for attention on newsstands and store shelves, AMAZING found it difficult to stand out.

Browne’s own separation from the past is perhaps most evident in the blurb he wrote for Arthur C. Clarke’s story, “Encounter in the Dawn,” in the second digest issue:

A lot of glib fiction has been written about life on other planets, with space ships dropping down among

alien races, zap guns decimating the enemy, while Our Hero goes battling off after a Beautiful Princess, who is about to be ravaged by the hairy-nosed glumpfx of Pluto. But Mr. Clarke . . . takes the realistic approach and gets better results than anything by the boom-boom boys.

So much for Ray Palmer’s “Gimme bang-bang” approach, which had been the cornerstone of AMAZING‘s editorial philosophy in the previous decade.

For a period in the second half of 1953, AMAZING could revel in its attempts to equal or better “The Big Three.” There were stories by Robert Sheckley (“Restricted Area,” June; “Beside Still Waters,” October; “The Perfect Woman,” December), Philip K. Dick (“The Commuter,” August; “The Builder,” December), and Henry Kuttner (“Or Else,” August), all of which stand the test of time. Richard Matheson contributed “Little Girl Lost” (October), which became the subconscious inspiration for Steven Spielberg’s 1982 film POLTERGEIST.

There were further quality stories from William P. McGivern, Evan Hunter (author of the 87th Precinct novels under the pseudonym Ed McBain), and Algis Budrys.

One noticeable feature of all the best stories from this period is that they are scarcely science fiction at all, but convey a deeper mood of the fantastic or the unnerving, bringing a more adult feel to the treatments of their themes. They were certainly far from the type of science fiction that had been contained in the earliest issues of Hugo Gemsback’s brainchild.

If there is one author whose work best represents the era of the early digest-format AMAZING, it is Walter M. Miller, Jr. He had three stories apiece in AMAZING and FANTASTIC during this time. “Death of a Spaceman” (AMAZING, March 1954) is typical. It isn’t a science-fiction story at all — it’s the memories of Old Donegal, a space pioneer, as he lies dying. Yet within the story Miller manages to convey the perils and the loneliness of space exploration better than in any thrill-a-minute adventure yarn. Joe De Bolt and John R. Pfeiffer, writing in Neil Barron’s ANATOMY OF WONDER (3rd edition, Bowker, 1987), said of Miller’s stories from this period that they brought “a depth of character and richness of meaning to sf unusual for the times and, with them, bridged the gulf from the pulps to the mainstream.” That was exactly the effect Browne wanted. Had he been able to keep Miller as a contributor, AMAZING may well have published his award-winning masterwork, “A Canticle for Liebowitz,” but instead this sold to THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION, where it began to appear in early 1955.

It is ironic, but perhaps not altogether surprising, that today we can look back at the early digest issues of AMAZING and remark upon the quality of the stories and the caliber of the writers. Yet at this time AMAZING was being outsold by rival magazines, some of which had little if any quality material in their contents. Browne’s roots were firmly in the pulp tradition, and he (and the magazine) remained a victim of that market; it could not be escaped overnight. Whereas three years earlier Browne’s dream of a quality slick magazine had been quashed before it was even born, now his heart was hit as the reality became a gathering nightmare. Another dream was shattered.

It is ironic, but perhaps not altogether surprising, that today we can look back at the early digest issues of AMAZING and remark upon the quality of the stories and the caliber of the writers. Yet at this time AMAZING was being outsold by rival magazines, some of which had little if any quality material in their contents. Browne’s roots were firmly in the pulp tradition, and he (and the magazine) remained a victim of that market; it could not be escaped overnight. Whereas three years earlier Browne’s dream of a quality slick magazine had been quashed before it was even born, now his heart was hit as the reality became a gathering nightmare. Another dream was shattered.

Within a year of the launch of the digest, AMAZING‘s budget was cut. The word rates dropped, the leading authors faded away, and the magazine became a dim shadow of its recent former self. Fairman left in the summer of 1954, leaving Browne to edit the magazine on his own, supported only by the Ziff-Davis secretarial staff.

Less than a year after the magazine’s brief golden period, we find Browne having to admit to a few problems. In the March 1955 issue, one letter writer took Browne to task, cataloguing all of the problems now plaguing AMAZING in its degeneration over the last year. He summed it up by asking, “What happened to this mag?” Browne responded:

Not enough readers will buy the magazine to justify the tremendous costs involved. It was your editor’s

argument that a magazine containing the best of everything in the science-fiction field — best paper for best reproduction of the best artwork illustrating the best stories, plus the use of color — would bring a couple of hundred thousand steady readers every issue. We were wrong — and the figures were not long in arriving to prove us wrong. Sure, circulation mounted, but nothing like it had to justify the expense involved. We stuck to our guns as long as we could, but the day arrived when retrenchment was in order. We hated to back down; but in view of the circumstances it would have been foolhardy not to.

Curiously, at this low ebb, Ziff-Davis decided to put AMAZING back on a monthly schedule, starting with the December 1955 issue. But this only meant more work for Browne, and with his dreams shattered, he lost interest in the magazines. He left them to more or less edit themselves. “Many of the stories appearing in the Ziff-Davis magazines were never read by me,” he told me some years ago. At the time when Fairman and Shaffer were supporting editors, this arrangement may have been fine, but it was probably not the case when Browne was editing solo. (After all, someone had to read them.) It is more likely that he has simply forgotten these years, during which he compiled the issues more as a chore than a mission. Instead, he spent his time writing two suspense novels, THIN AIR and THE TASTE OF ASHES, the first books published under his own name. He was delighted when, in 1956, he received a call from a television producer who had read the books and invited Browne out to Hollywood to try his hand as a screenwriter.

Browne jumped at the chance, though he took a few months’ leave of absence first before taking the plunge full-time. To cover for him as editor, Browne called back Paul W. Fairman. Fairman had still been writing regularly for the Ziff-Davis magazines, sometimes almost filling entire issues under a collection of house names.

Fairman and Browne worked together in compiling AMAZING‘s bumper 30th anniversary issue for April 1956. The fiction in it was all reprinted material, selected from the magazine’s archives, but the nonfiction was new, including a whole cabinet of curiosities where personalities of the day were asked for their predictions about what the year 2001 would be like. The luminaries included Salvador Dali, Dr. Robert Lindner, Philip Wylie, Steve Allen, and Sid Caesar (who was uncanny in his prediction of global television).

Shortly after that issue hit the stands, Browne hit the road. Fairman took over full responsibility for the magazines, assisted by a young woman, Cele Goldsmith, who had recently been brought onto the payroll to help Browne with an ill-fated correspondence magazine called PEN PALS.

Fairman’s style of editing was not Browne’s. He was a production-line writer, and had cut his teeth on the Palmer issues of the magazine. He saw no problems with the old policy of authors writing a set monthly wordage and publishing the stories under house names. After all, that’s what he did with his own work. So, back came E. K. Jarvis, Gerald Vance, and P. F. Costello to join Ivar Jorgensen, Lee Archer, Clyde Mitchell, and other names designed to deceive — only this time the real writers had changed.

The bulk of the copy in AMAZING during the mid to late 1950s was produced by the latest generation of writers: Robert Silverberg, Milton Lesser, Harlan Ellison, Henry Slesar, Randall Garrett, and Fairman himself. Although the younger ones were still learning their trade, these were all good writers, and while they might now disown what they churned out for AMAZING and FANTASTIC during those days, much of it was readable by the standards of the time. Its main trouble was that it was predictable, formula material, using standard plots and characters. Fairman enjoyed basic conflict stories, usually man versus environment, or man against enormous odds, with man invariably triumphant at the end. Those by Garrett were often lighthearted, those by Silverberg charmingly innocent, and those by Ellison harsh and downbeat. Otherwise they were basically the same story.

The bulk of the copy in AMAZING during the mid to late 1950s was produced by the latest generation of writers: Robert Silverberg, Milton Lesser, Harlan Ellison, Henry Slesar, Randall Garrett, and Fairman himself. Although the younger ones were still learning their trade, these were all good writers, and while they might now disown what they churned out for AMAZING and FANTASTIC during those days, much of it was readable by the standards of the time. Its main trouble was that it was predictable, formula material, using standard plots and characters. Fairman enjoyed basic conflict stories, usually man versus environment, or man against enormous odds, with man invariably triumphant at the end. Those by Garrett were often lighthearted, those by Silverberg charmingly innocent, and those by Ellison harsh and downbeat. Otherwise they were basically the same story.

Silverberg’s first story for AMAZING was “Hole in the Air” (January 1956), the start of a relationship which, thirty-five years later, is still going strong. Silverberg — under his own name and numerous pseudonyms — is AMAZING‘s most prolific contributor. (Robert Silverberg is still associated with AMAZING STORIES as a member of the magazine’s Editorial Advisory Board.)

In addition to his affinity for basic conflict stories, Fairman also believed that sex helped sell issues. He spiced up story titles, and even launched a magazine of wish-fulfillment stories with a heavy emphasis on sex, called DREAM WORLD. This publication arose following the success of a special “dream” issue of FANTASTIC, but DREAM WORLD was not everyone’s heart’s desire, and it lasted only three issues (February, May, and August 1957).

Little of merit survives from the Fairman years. The 1950s were the days of the science-fiction B-movies, and Fairman seemed to equate sf too closely with the archetypal monster movie or alien invasion. Indeed, the movie industry inspired another companion magazine, AMAZING STORIES SCIENCE FICTION NOVEL, which attempted to bridge the gap between paperbacks and magazines. It saw only one issue, in June 1957, which consisted of a novelization by Henry Slesar of the Columbia film 20 MILLION MILES TO EARTH.

Fairman also had a passion for UFOs, and he made the October 1957 AMAZING STORIES a “special flying saucer issue.” Apart from two UFO stories, written pseudonymously by Algis Budrys (“If These Be Gods” by “Gordon Jaylyn”) and Harlan Ellison (Farewell to Glory” by “Ellis Hart”), the issue was given over to a “Flying Saucer Forum,” with contributions from Ray Palmer, Kenneth Arnold, Gray Barker, Richard Shaver, and the United States Air Force.

Although many people were interested in the UFO enigma, not all readers would have welcomed the return of Shaver to AMAZING‘s pages. But there was more to come. Fairman devoted much of the July 1958 FANTASTIC to the Shaver Mystery. The circulation of both magazines was dropping, and it looked as if Fairman was following Palmer’s lead of the previous decade by pandering to the fringe cults.

Fairman had, until this time, been able to indulge himself because Bernard Davis (whose primary interest had been the fiction magazines) had stepped down as president of the company in July 1957. He bought Mercury Publications, which published THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION and ELLERY QUEEN’S MYSTERY MAGAZINE, and established his own Davis Publications. The company continues to this day in the hands of his son, Joel Davis, and publishes ISAAC ASIMOV’S SCIENCE FICTION MAGAZINE and ANALOG (formerly ASTOUNDING), among other titles. (Davis sold its magazines to Bantam Doubleday Dell in 1992. In 1996, Dell Magazines was acquired by Crosstown Publications and became part of Penny Publications. ASIMOV’S and ANALOG are now published by Penny Press/Dell Magazines.)

The new publisher of AMAZING, Michael Michaelson, who was also vice president in charge of circulation, was not as indulgent, and was anxious to see AMAZING paying its way. Changes were in store. In September 1958 Fairman left Ziff-Davis to return to writing, which he did with moderate success under a host of pseudonyms until his death in 1977. His place was taken by his assistant, Cele Goldsmith.

The Fairman years saw AMAZING at its worst, equating with the dullness of the Sloane era twenty years before. The magazine was read predominantly by young people, to whom it clearly appealed (a pen-pal column, “The Space Club,” brought responses mostly from readers in the 12-to-15 age range), but they were turning more to comics and television. The time was due to change AMAZING‘s image again, and seek a new market. Cele Goldsmith felt up to that challenge. She assumed the editorship of AMAZING with its December 1958 issue, and started the climb back to glory. We’ll revel in her success on Thursday, March 3rd, in the next segment in our series.

The Fairman years saw AMAZING at its worst, equating with the dullness of the Sloane era twenty years before. The magazine was read predominantly by young people, to whom it clearly appealed (a pen-pal column, “The Space Club,” brought responses mostly from readers in the 12-to-15 age range), but they were turning more to comics and television. The time was due to change AMAZING‘s image again, and seek a new market. Cele Goldsmith felt up to that challenge. She assumed the editorship of AMAZING with its December 1958 issue, and started the climb back to glory. We’ll revel in her success on Thursday, March 3rd, in the next segment in our series.

“The AMAZING Story: The Fifties — Dream Worlds” is © 2016 by Mike Ashley and appears here with the author’s permission. Notes in italics are by PulpFest and are © 2016 by PulpFest. The original article was published by TSR, Inc. and edited by Kim Mohan for the April 1992 issue of AMAZING STORIES. Many thanks to Curt Phillips, the moderator of the Yahoo newsgroup PulpMags, for drawing our attention to and providing us with copies of Mike Ashley’s exceptional series of articles about the world’s first science-fiction magazine. Please visit pulpcon.org on Thursday, March 3rd, for the fifth segment of the series.

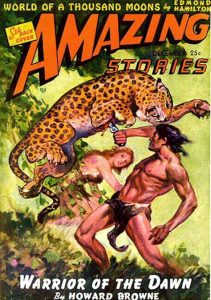

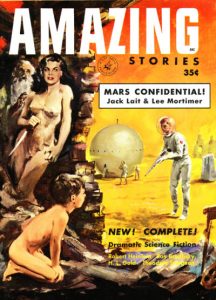

(Concerning our illustrations . . . . Howard Browne assumed the editorship of AMAZING STORIES beginning with the January 1950 number, remaining in that capacity through the August 1956 number. He had become associated with the magazine in the early forties when then-editor Ray Palmer convinced him to write a novel set in prehistoric times, “Warrior of the Dawn,” which Palmer serialized in late 1942 and early 1943. The first segment of Browne’s story was featured on the cover of the December 1942 AMAZING with cover art by the incomparable J. Allen St. John, best known for his illustrations of the novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

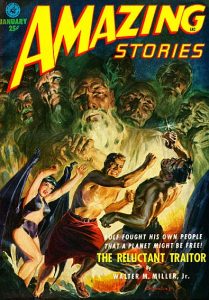

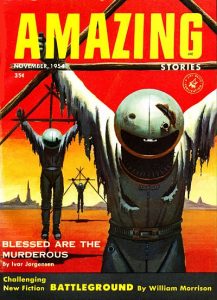

One of the best writers who contributed to AMAZING during the 1950s was Walter M. Miller, Jr. His first professional sale — “Secret of the Death Dome” — appeared in the January 1951 issue. Later in the decade, Miller would sell the serial rights to his classic novel “A Canticle for Liebowitz” to THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION. During the fifties, Miller contributed a dozen stories to AMAZING and its companions — FANTASTIC ADVENTURES and FANTASTIC. “The Reluctant Traitor” appeared in the January 1952 AMAZING STORIES. The issue featured cover art by Norman Saunders, a prolific and talented illustrator who contributed work to the pulps, slicks, digests, paperbacks, comic books, men’s adventure magazines, and trading cards.

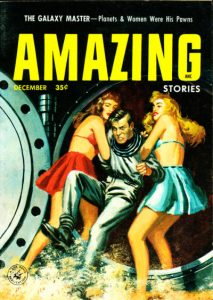

Although AMAZING STORIES published some fine stories during the fifties, it was largely a “routine space-adventure magazine” for much of the decade, publishing stories in the vein of Edgar Rice Burroughs. These included the Michael Flannigan trilogy, written by Stuart J. Byrne under the alias of John Bloodstone. The middle story in the trilogy — “The Golden Gods” — appeared in the April 1952 number, with a front cover painting rendered by Barye Phillips, an artist who created many paperback covers for Gold Medal and other Fawcett imprints during the 1950s. He also painted covers for Avon, Bantam, Dell, Pocket Books, and Signet and was referred to throughout the industry as “The King of the Paperbacks.”

In addition to his work for the paperback industry during the 1950s, Barye Phillips also contributed four covers to AMAZING STORIES and two covers to FANTASTIC, including its first issue, the Summer 1952 number. Phillips created the cover with Leo R. Summers, who served as the art director for the magazine. Summers also painted about thirty covers for AMAZING and its companions during the 1950s and sixties.

The success of the digest FANTASTIC led Ziff-Davis to convert its science-fiction title, AMAZING STORIES, to the same format. Its first digest issue was the April/May 1953 number, with another cover by Barye Phillips. Inside were stories by Ray Bradbury, editor Howard Browne, Alfred Coppel, H. L. Gold, Robert Heinlein, Murray Leinster, Richard Matheson, and Theodore Sturgeon. It’s hard to imagine a better line-up for the magazine’s debut as a digest.

Looking at the early digest issues of AMAZING STORIES, one sees many of the greats of science fiction and fantasy — Robert Bloch, Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, Gold, Heinlein, Frank Herbert, Henry Kuttner, Leinster, Matheson, Walter M. Miller, Jr., Robert Sheckley, Sturgeon, and others — listed on their contents pages. It is difficult to surmise why the magazine wasn’t selling, but competition was stiff. Within a year after its conversion to the digest format, AMAZING had reverted to a “routine space-adventure magazine.” The November 1954 issue — with a rather downbeat cover painting by Edward Valigursky (using the pseudonym William Rembach) — was one of its last quality issues, featuring stories by Bloch, Herbert, John Jakes, Milton Lesser, and others.

Edward Valigursky studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, the American Academy of Arts, and the Art Institute of Pittsburgh. He began to sell drawings to pulp magazines while still an art student. In 1952, he moved to New York City and began working as an associate art director for Ziff-Davis. He also worked as a freelance artist, contributing interior illustrations and cover art to AMAZING STORIES, DREAM WORLD, FANTASTIC, FANTASTIC ADVENTURES, IF, STARTLING STORIES, and such men’s adventure magazines as ARGOSY, SAGA, and TRUE ADVENTURE. He painted over eighty covers for the Ziff-Davis fantasy and science-fiction magazines — including the December 1956 AMAZING STORIES — and more than 100 paperback covers for Ace Books. He later turned to advertising art and illustrating for magazines such as COLLIER’S and POPULAR MECHANICS.

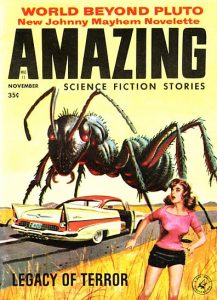

Howard Browne left Ziff-Davis in 1956, turning things over to Paul Fairman. Little of merit survives from Fairman’s period as the editor of AMAZING STORIES and FANTASTIC. The late fifties “were the days of the science-fiction B-movies, and Fairman seemed to equate sf too closely with the archetypal monster movie.” The November 1958 issue of the magazine — with art again by Ed Valigursky — features a monstrous ant on the front cover. Valigursky’s creature is remindful of the “giant man-eating monsters that threaten civilization” in the 1954 Warner Brothers science-fiction movie, THEM!