The AMAZING Hugo Gernsback

One of the major themes of PulpFest 2016 will be the 90th anniversary of the premiere of the first continuing science-fiction magazine, AMAZING STORIES. In November 2015, PulpFest programming and marketing director Mike Chomko contacted author, anthologist, and science-fiction and popular culture historian Mike Ashley, asking him to be a guest at PulpFest 2016. Due to a scheduling conflict, Mr. Ashley declined to attend. However, he did grant us permission to post his series of seven articles concerning the history of AMAZING STORIES — originally offered in the January through July 1992 issues of AMAZING STORIES. We’ll be posting the entire series, releasing one article every Monday and Thursday over the next few weeks.

Many thanks to Curt Phillips, the moderator of the Yahoo newsgroup PulpMags, for drawing our attention to and providing us with copies of Mike Ashley’s exceptional series of articles about the world’s first science-fiction magazine.

“The AMAZING Story: The Twenties — By Radio to the Stars” is © 2016 by Mike Ashley and appears here with the author’s permission. Notes in italics are by PulpFest and are © 2016 by PulpFest. The original article was published by TSR, Inc. and edited by Kim Mohan for the January 1992 issue of AMAZING STORIES.

Ninety years ago there were no science-fiction magazines. In fact, there was no such thing as “science fiction”; the name had yet to be coined. There were stories called scientific romances — H. G. Wells had written scores of them. There were also weird stories, off-trail stories, “different” stories, uncanny stories, and among all of these were stories we would now call science fiction — a rose by any other name. But before 1926 the category had yet to be created, and fans who enjoyed these weird-scientific stories had no regular magazine in which to find them.

Ninety years ago there were no science-fiction magazines. In fact, there was no such thing as “science fiction”; the name had yet to be coined. There were stories called scientific romances — H. G. Wells had written scores of them. There were also weird stories, off-trail stories, “different” stories, uncanny stories, and among all of these were stories we would now call science fiction — a rose by any other name. But before 1926 the category had yet to be created, and fans who enjoyed these weird-scientific stories had no regular magazine in which to find them.

In the years after World War I the interest in this type of story grew rapidly. For the best in escapist fiction, millions of Americans read the pulp magazines, and the magazines with the most escapist fantasies were published by Frank A. Munsey, in particular THE ARGOSY and THE ALL-STORY MAGAZINE. It was in THE ALL-STORY that Edgar Rice Burroughs first appeared, in 1912, with his adventures of John Carter in “Under the Moons of Mars.” This was followed a few months later by “Tarzan of the Apes.” The Munsey magazines became the principal market for scientific romances and fantastic adventures. By the start of the twenties they had a regular stable of writers, including George Allan England, Homer Eon Flint, Murray Leinster, Ray Cummings, Austin Hall, Garret Smith, and A. (Abraham) Merritt. These were the leading writers of the scientific romance in the pulps, one of whom — Leinster — would stay at that core for the next fifty years. The type of story they wrote then was light on science, high on adventure or concept, and high on fantastic imagery. The stories appealed to that desire we all have to escape from this mundane, depressing world and discover a world of wonder. The most popular of them all were Burroughs and Merritt, and each, in his way, set the standard for the scientific adventure fantasies of the twenties.

While this line of scientific adventure was emerging in the pulps, another development was taking place — a revolutionary development. The architect of this revolution was Hugo Gernsback, and it was from his errant hybrid that the early world of science fiction, and AMAZING STORIES, would sprout.

Hugo Gernsback was born in Luxembourg in 1884, the son of a prosperous wine merchant. In his youth he developed a fascination with electrical gadgets, and by his teens he was a fertile inventor. He emigrated to the United States in 1904, after the death of his father, in the hope of making a fortune from his invention of a powerful dry-cell battery. The device proved too expensive to produce but, undaunted, Gernsback constructed a smaller battery, which he sold to the Packard Motor Car Company.

Gernsback’s main interest at this time, though, was in radio. He was surprised how difficult it was to obtain the necessary parts to construct wireless telegraphy units in New York, so in 1905 he established a company to import electrical equipment. It was this Electro-Importing Company that was to be the foundation of his publishing empire. In 1906 Gernsback marketed a portable wireless telegraph transmitter and receiver at the seemingly impossible price of $7.50. Skeptics believed he was a fraud, and a policeman was dispatched to verify Gernsback’s claim. Gernsback demonstrated his device, though the policeman remained unconvinced. “I still think yez are fakers,” he told Gernsback. “Yer ad here sez it is a wireless set, so what are all dem here wires for?”

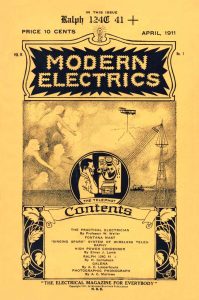

It was this incident that spurred Gernsback on to publish a magazine. He later recalled, “It rankled me that there could be such ignorance in regard to science, and I vowed to change the situation if I could. A few years later I brought out the world’s first radio magazine, MODERN ELECTRICS, to teach the young generation science, radio, and what was ahead for them.”

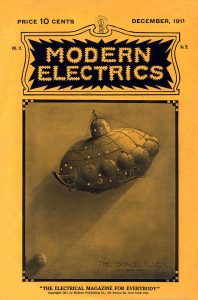

It was the “what was ahead for them” aspect with which Gernsback became so closely associated. He loved to speculate about potential inventions and to encourage his readers to experiment. He targeted this encouragement chiefly at the young, who had the more fertile and flexible minds. To further encourage them he turned his speculative thoughts into a story, “Ralph 124C 41+,” which was serialized in MODERN ELECTRICS during 1911-12.

Actually, to call this piece a “story” is rather generous, because Gernsback was only using the narrative form to liven up what was otherwise a catalogue of future inventions. He explored the world of the year 2660 from the viewpoint of one of the world’s great scientists. Each month readers were treated to extravagant scientific speculations, and there was even a chase scene in one episode when Ralph’s girl, Alice, was kidnapped by Martians, and Ralph pursued them. It was in that episode that Gernsback made one of his most remarkable predictions by describing exactly how radar would work, more than twenty years before it was “discovered” by Robert Watson-Watt.

Actually, to call this piece a “story” is rather generous, because Gernsback was only using the narrative form to liven up what was otherwise a catalogue of future inventions. He explored the world of the year 2660 from the viewpoint of one of the world’s great scientists. Each month readers were treated to extravagant scientific speculations, and there was even a chase scene in one episode when Ralph’s girl, Alice, was kidnapped by Martians, and Ralph pursued them. It was in that episode that Gernsback made one of his most remarkable predictions by describing exactly how radar would work, more than twenty years before it was “discovered” by Robert Watson-Watt.

The difference between Gernsback’s adventures of Ralph and the stories appearing in the Munsey magazines was quite fundamental. The Munsey stories were high on entertainment, low on scientific accuracy. They were predominantly fantastic adventures or, at the shorter length, scientific mysteries, with the emphasis on the weird and wonderful. The writers were competent pulpsters able to unravel a strong, compelling story with a fanciful theme.

Gernsback’s story was low on entertainment, but deliberately high on scientific accuracy and speculation. He was no storyteller; he was no writer at all. It was not his intention to entertain but to educate and, he hoped, to stimulate his readers to become creative and inventive. It was this motive that led, by stages, to the birth of AMAZING STORIES. And it was this difference that initially separated Gernsback’s scientific fiction from the pulp scientific adventures.

In 1913 Gernsback sold MODERN ELECTRICS and founded a new magazine, THE ELECTRICAL EXPERIMENTER, which broadened Gernsback’s coverage beyond radio to all aspects of scientific achievement. Gernsback was now vociferously encouraging readers to become inventors and to build their own future. Along that road, Gernsback averred, lay fame and fortune, and he cited Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, and Guglielmo Marconi as model examples. Writing in the April 1916 ELECTRICAL EXPERIMENTER, Gernsback said:

A world without imagination is a poor place to live in. No real electrical experimenter, worthy of the name, will ever amount to much if he has no imagination. He must be visionary to a certain extent, he must be able to look into the future and if he wants fame he must anticipate the human wants. It was precisely this quality which made Edison — a master of imagination — famous.

THE ELECTRICAL EXPERIMENTER began to publish fiction regularly by a variety of almost unknown writers — George F. Stratton, Charles M. Adams, Harlan Eveleth — names as remote and lost as the crew of the Marie Celeste. Every one of their stories was awful, but as scientific speculation they were enlightening. Because it was wartime, many of the stories speculated on devices to help win the war, such as anti-gravitation to cause havoc among the enemy, or a concentrated electron ray (not unlike a laser beam) to detonate enemy explosives.

In 1920 Gernsback retitled the magazine SCIENCE AND INVENTION, to emphasize that he had moved beyond the basic role of the experimenter toward the vaster world of science and technology. Gernsback was an evangelist of science determined to educate the American public and even more determined to inspire them into scientific achievement. He, probably more than any of his contemporaries, opened the eyes of the American public to the possibilities of science and the wonders to come. Through the stimulation of his magazines, he could inspire them to build their future world.

In 1920 Gernsback retitled the magazine SCIENCE AND INVENTION, to emphasize that he had moved beyond the basic role of the experimenter toward the vaster world of science and technology. Gernsback was an evangelist of science determined to educate the American public and even more determined to inspire them into scientific achievement. He, probably more than any of his contemporaries, opened the eyes of the American public to the possibilities of science and the wonders to come. Through the stimulation of his magazines, he could inspire them to build their future world.

The closest anyone came to publishing a magazine of scientific stories before AMAZING STORIES was with THE THRILL BOOK and WEIRD TALES. THE THRILL BOOK came from Street & Smith in 1919, and though its original concept had been to publish scientific romances, when it appeared it concentrated on adventure stories, a few with fantastic elements. WEIRD TALES, launched in Chicago in March 1923, was always intended as a horror magazine but did carry some stories of the monster-in-the-laboratory type, and later some space adventures, mostly by Edmond Hamilton.

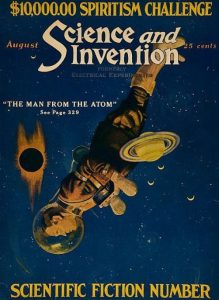

Gernsback was so taken with the idea of promoting science through fiction that he seriously considered issuing such a magazine in 1923. That year he made the August issue of SCIENCE AND INVENTION a “Scientific Fiction Number.” It contained five complete stories, plus an episode of Ray Cummings’s serial “Around the Universe.” The stories were, by and large, boring, although there was something special in “The Man From the Atom” by precocious fifteen-year-old G. Peyton Wertenbaker. This story, about a man who escapes from our universe into a macro-universe beyond, is still readable today.

We do not know the reader reaction to the issue since, at that time, the magazine ran no letter column. When it did run a letter column, it was evident that the stories Gernsback published were favorably received, and that may well have been the case here. In any case, a few months later Gernsback gave thought to launching a new magazine, to be called SCIENTIFICTION. He made no reference to this fact in his magazines at the time, but, as he later recalled, he sent a flyer to his subscribers attempting to gauge interest. The response was, apparently, dispiriting, so Gernsback did not pursue the venture. He seemingly had enough to handle at that point anyway, since in June 1925 he launched his own radio station, WRNY, the first such enterprise in New York City.

Had there been a greater positive response to the circular, the history of magazine science fiction might have started two years earlier, and that turn of events may have had a significant impact on its later evolution, which, as we shall later see, became fast-paced. I imagine that the main reason why the response was lukewarm was that Gernsback targeted the wrong market. Those most likely to subscribe to his technical magazines would have been professional scientists, engineers and radio enthusiasts, both experimenters and hobbyists, who may have appreciated the stories in SCIENCE AND INVENTION as novelty items but would have expressed no great interest in a specialist magazine. It was much more likely to have appealed to the newsstand browser (from which most of the general pulp readers came) — those who could not necessarily afford to subscribe to a magazine, or had no reason to. To the browser, it was much more fun looking at all of the pulps on display and relishing the thrills promised by the covers.

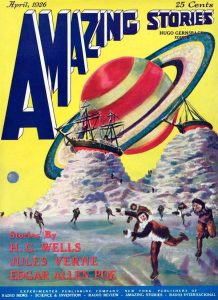

This Gernsback was to discover when, in 1926, he acted on impulse (as he so often did) and launched the world’s first science-fiction magazine, AMAZING STORIES. Its premiere issue, dated April 1926, was released on March 10. It was in the same format as SCIENCE AND INVENTION, having a larger page size (8 by 11 inches) than the usual pulp, which thus set it apart. In addition it had a gaudy, eye-catching cover by Frank R. Paul, an Austrian-born artist and draftsman who had been illustrating the majority of the stories in SCIENCE AND INVENTION since 1918. The first issue, with a print run of 100,000, sold out. Gernsback was onto a winner.

This Gernsback was to discover when, in 1926, he acted on impulse (as he so often did) and launched the world’s first science-fiction magazine, AMAZING STORIES. Its premiere issue, dated April 1926, was released on March 10. It was in the same format as SCIENCE AND INVENTION, having a larger page size (8 by 11 inches) than the usual pulp, which thus set it apart. In addition it had a gaudy, eye-catching cover by Frank R. Paul, an Austrian-born artist and draftsman who had been illustrating the majority of the stories in SCIENCE AND INVENTION since 1918. The first issue, with a print run of 100,000, sold out. Gernsback was onto a winner.

Fortunately, Gernsback had not filled the magazine with stories that were typical of those in SCIENCE AND INVENTION. The first issue contained all reprints, with classic selections from H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Edgar Allan Poe, a pulp reprint by Austin Hall from ALL-STORY, and the two best stories he had previously published, Wertenbaker’s “The Man From the Atom” and “The Thing From — Outside” by George Allan England, one of the more popular adventure writers for the pulps.

The success of AMAZING, however, put Gernsback into a dilemma. The type of “scientifiction” (as he then called it) that readers most enjoyed were stories of scientific adventure that contained less technological speculation than he desired. During the preceding few years in SCIENCE AND INVENTION, Gernsback had run a series of stories by Clement Fezandié, a New York teacher and businessman, under the general title of “Doctor Hackensaw’s Secrets.” These stories were really thinly disguised lectures. In each episode, Hackensaw waffled on about his latest invention, regardless of its effects upon the world or humanity. Forty years later, Gernsback still referred to Fezandié as a “titan of science fiction,” which suggests the type of story that he most liked. But, when Gernsback asked the readership of AMAZING STORIES if they would like to see a continuation of the Hackensaw series in the new magazine, he got an emphatic NO. The demand was for stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs and A. Merritt — tales from the Munsey school of scientific romance. Although Gernsback claimed he had a number of Fezandié’s stories in stock, he only published two in AMAZING, in the third and fourth issues he put out. It rapidly became evident that his newfound readers were not so interested in scientific expostulation but cared far more for scientific extravaganza.

Striving to find a middle ground, Gernsback balanced reprints from the pulps and classics by Verne and Wells against a variety of gadget stories that he hoped would educate and inspire. But he was soon being lectured to by his readers and writers. In a letter that Gernsback published in his July 1926 editorial, Wertenbaker, his first significant discovery, warned him that “the danger that may lie before AMAZING STORIES is that of becoming too scientific and not sufficiently literary.”

Gernsback found that he had to compromise his principles. If he had to publish fantastic adventures in order to attract readers, then he would do so, provided that he could also inspire them with a selection of gadget stories. His biggest conflict in this regard came with the serialization of Merritt’s “The Moon Pool” in 1927. He found himself justifying the inclusion of the story in the magazine by arguing about the advanced science projected by Merritt. Although the story does contain some scientific speculation, it’s basically hocus-pocus that was included by Merritt when he wrote a novel-length sequel to his original fantastic short story, published in ALL-STORY in 1919. In his heart of hearts, Gernsback knew that the science in this story was of dubious authenticity, and that knowledge played heavily on his conscience.

Another challenge was Frank R. Paul’s garish covers. There was no doubt that Paul’s exciting drawings attracted a wide readership, predominantly young males, but they also caused the magazine to become associated with sensationalistic trash. Yet when Gernsback experimented with a serious symbolical cover in 1928, that issue suffered a drop in sales of 22 percent.

Another challenge was Frank R. Paul’s garish covers. There was no doubt that Paul’s exciting drawings attracted a wide readership, predominantly young males, but they also caused the magazine to become associated with sensationalistic trash. Yet when Gernsback experimented with a serious symbolical cover in 1928, that issue suffered a drop in sales of 22 percent.

In fact, by 1928 — a year that saw an explosion in new writing talent — Gernsback had more or less accepted that AMAZING STORIES had outgrown his original premise. The kind of gadget story that he obviously liked and had intended to serve as inspiration — such riveting classics as “An Experiment in Gyro-Hats” by Ellis Parker Butler (June 1926), “The Automatic Self-Serving Dining Table” by Henry Hugh Simmons (April 1927), and “The Tide Projectile Transportation Co.” by Will H. Gray (September 1927) — had become dead weight. Readers were clamoring for the scientific extravaganzas that had initially been represented by reprints selected by Gernsback’s adviser, C. A. Brandt — “A Columbus of Space” by Garrett P. Serviss (August through October 1926), ‘The Red Dust” by Murray Leinster (January 1927), “The Land That Time Forgot” by Edgar Rice Burroughs (February through April 1927), and, of course, “The Moon Pool” by A. Merritt (May through July 1927), the most popular story published in AMAZING‘s first few years. All of these had first appeared in the Munsey pulps.

Moreover, the writers now establishing themselves were not producing the gadget story in any quantity, but were writing the scientific extravaganza in emulation of the Munsey pulps. The first regular writer to establish himself in AMAZING STORIES was archaeologist A. Hyatt Verrill, who became noted for adventure stories set in lost valleys, typical of the Munsey locales. Then there was Edmond Hamilton, who became a regular after the January 1928 issue. He had been selling super-science sagas to WEIRD TALES for two years, and had cut his teeth on reading the Munsey pulps. Jack Williamson, who is still writing today (Williamson continued writing until his death in 2006, long after the original publication of this article), first appeared in the December 1928 issue with “The Metal Man,” a story blatantly inspired by Merritt’s writings. And we should not forget H. P. Lovecraft, the doyen of WEIRD TALES, who sold arguably his best story to AMAZING STORIES, “The Colour Out of Space” (September 1927). Lovecraft had also been a great fan of the Munsey pulps, and though this story was probably more inspired by Algernon Blackwood than by Abraham Merritt, it reflects far more the imagery of the Munsey visionaries than that of Gernsback’s electro-philiacs.

Probably the only authors not directly influenced by the Munsey pulps were the doctors David H. Keller and Miles J. Breuer. Yet even these writers, despite their scientific training, turned more to the non-technological sciences.

Keller had a greater social conscience than most other writers, and in “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” (February 1928), “A Biological Experiment” (June 1928), and other stories he projected the human element of scientific advance. He had a sharp mind and an eye for detail, which lent strength to the messages in his stories. Breuer was fascinated by the mathematics of other dimensions and produced a range of fascinating stories exploring the concepts of the fourth and fifth dimensions.

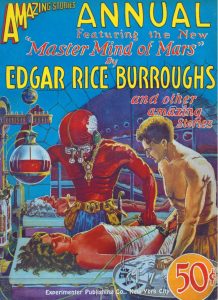

By and large Keller and Breuer were the exceptions, not the rule. They wrote the intelligent novelty items, not the mind-blowing scientific adventures. The selling power of the latter was evident when, in celebration of the first year’s success of AMAZING, Gernsback released an AMAZING STORIES ANNUAL. As the lead novel in this bumper issue — twice as thick as the regular monthly magazine — Gernsback secured a new Martian novel from Edgar Rice Burroughs, “The Master Mind of Mars.” Even though the ANNUAL was twice the price of the monthly, it sold out within a few weeks. Its success led Gernsback to establish an AMAZING STORIES QUARTERLY companion magazine featuring all-new material.

By and large Keller and Breuer were the exceptions, not the rule. They wrote the intelligent novelty items, not the mind-blowing scientific adventures. The selling power of the latter was evident when, in celebration of the first year’s success of AMAZING, Gernsback released an AMAZING STORIES ANNUAL. As the lead novel in this bumper issue — twice as thick as the regular monthly magazine — Gernsback secured a new Martian novel from Edgar Rice Burroughs, “The Master Mind of Mars.” Even though the ANNUAL was twice the price of the monthly, it sold out within a few weeks. Its success led Gernsback to establish an AMAZING STORIES QUARTERLY companion magazine featuring all-new material.

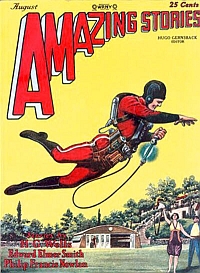

The old order of Gernsback’s gadget stories was finally blasted out of existence with the August 1928 issue of AMAZING STORIES. This was the most important issue Gernsback was to publish, and is one of the most significant issues of AMAZING. It contained two profoundly influential stories, E. E. (Doc) Smith’s serial “The Skylark of Space” and Philip Francis Nowlan’s novella “Armageddon — 2419 A.D.”

Smith’s work was the literary equivalent of a nuclear attack. Hitherto most of Gernsback’s scientifiction had been relatively sedate, confined to Earth-bound experiments or explorations. Some stories had ventured to the Moon and neighboring planets, but only a rare few (those by Ray Cummings and J. Schlossel, plus some of the work of Edmond Hamilton in WEIRD TALES) had gone beyond the boundaries of the solar system. Smith blasted through all this. In his story, superscientist Richard Seaton discovers atomic energy, builds a spaceship, and sets off to explore the Universe, pursued by the villainous, though equally super-scientific, Blackie DuQuesne. It was a scientific extravaganza par excellence, and the readers went wild. “The Skylark of Space” became the archetypical work of space opera.

Nowlan’s novella did for the future what Smith’s novel did for outer space. Anthony Rogers, an engineer, is trapped in a mine but is revived five centuries hence. The United States is now dominated by a super-scientific Mongolian race, the Han. Rogers joins forces with a guerrilla faction to overthrow the enemy. In this story, and its sequel “The Air-lords of Han” (March 1929), Nowlan creates a fascinating range of future weaponry, combining action, adventure, and scientific speculation. Anthony Rogers went on to be converted into the comic-strip hero Buck Rogers, a name synonymous with early science fiction.

Nowlan’s novella did for the future what Smith’s novel did for outer space. Anthony Rogers, an engineer, is trapped in a mine but is revived five centuries hence. The United States is now dominated by a super-scientific Mongolian race, the Han. Rogers joins forces with a guerrilla faction to overthrow the enemy. In this story, and its sequel “The Air-lords of Han” (March 1929), Nowlan creates a fascinating range of future weaponry, combining action, adventure, and scientific speculation. Anthony Rogers went on to be converted into the comic-strip hero Buck Rogers, a name synonymous with early science fiction.

This is what the readers wanted — superscience. Gone were the relatively mundane tales of everyday inventions and new uses for radio. The possibilities of science fiction were blown wide open. Readers wanted their imaginations stretched beyond the horizons of tomorrow, and Gernsback could deliver nothing less. His “scientifiction” brainchild had rapidly grown out of all proportion and was threatening to veer out of control. For the moment he was prepared to let it go, though he had no idea of the consequences.

Gernsback’s original ideal had been to create a vehicle that would transport his experimenters into tomorrow, or more appropriately inspire his experimenters to create tomorrow. Within three years of its launch, AMAZING STORIES had become the vessel by which science fiction had set a course for the stars. But the science fiction that emerged was not Gernsback’s baby. It was the Munseyesque-pulp scientific romance that ruled the day, with its fantastic excesses tempered by Gernsback’s furnace of science.

Gernsbackian scientifiction, which had been born in MODERN ELECTRICS in 1911, had all but died in 1928, but it wasn’t extinct yet. While it was exerting its influence on the scientific romance to create the super-science epic, it was itself evolving and recovering, and would emerge anew in the 1930s.

Gernsbackian scientifiction, which had been born in MODERN ELECTRICS in 1911, had all but died in 1928, but it wasn’t extinct yet. While it was exerting its influence on the scientific romance to create the super-science epic, it was itself evolving and recovering, and would emerge anew in the 1930s.

Within a few months of publishing “The Skylark of Space,” Gernsback lost control of AMAZING STORIES, as a consequence of financial mismanagement in his many business dealings. (Those interested in the specifics of the incident will find it discussed in great detail in Tom Perry’s article “Experiment in Bankruptcy” in the May 1978 issue of AMAZING STORIES.) The consequences of this event were significant, and that’s where we pick up “The Amazing Story” on Monday, February 22nd.

Concerning our illustrations . . . . Hugo Gernsback introduced the first radio magazine — MODERN ELECTRICS — in 1908. Hoping to encourage his readers to experiment and learn more about science, he began serializing a story, “Ralph 124C 41+,” beginning with the April 1911 issue. Although the cover artist is not credited, it resembles the work of George Westcott, an artist who had produced some of the magazine’s earlier covers. Written by Gernsback himself, “Ralph 124C 41+” ran for twelve consecutive issues including the December 1911 number, the second magazine pictured in our article, with cover art by Thomas Wrenn.

The “Scientific Fiction Number” of Gernsback’s SCIENCE AND INVENTION was dated August 1923 and featured featured six “scientifiction” stories, including G. Peyton Wertenbaker’s “The Man from the Atom,” the inspiration for Howard V. Brown’s front cover art. Much of the “science fiction” that appeared in SCIENCE AND INVENTION revolved around a scientific principle, particularly the stories of Clement Fezandié, an author much favored by the publisher.

The debut issue of the first science-fiction pulp — AMAZING STORIES — was dated April 1926 and featured front cover art by Frank R. Paul, the “grandfather of science-fiction art.” An Austrian-born artist and draftsman who had been illustrating the majority of the stories in SCIENCE AND INVENTION since 1918, Paul was a mainstay for Gernsback throughout his career as a publisher.

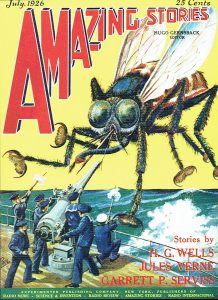

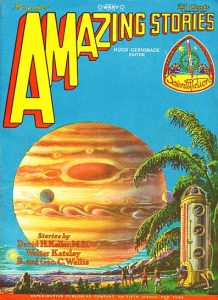

One rule of publishing that hasn’t changed in 90 years is that a magazine cover, first and foremost, must be eye-catching. Frank Paul’s covers for the July 1926 AMAZING STORIES and the AMAZING STORIES ANNUAL for 1927 are certainly that. And the authors in the magazines — Edgar Rice Burroughs, Austin Hall, A. Merritt, Edgar Allan Poe, Garrett P. Serviss, Curt Siodmak, A. Hyatt Verill, Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, and others — certainly didn’t hurt sales. Paul’s cover for the August 1928 issue of AMAZING STORIES — featuring the start of E. E. Smith’s “Skylark of Space” and the first Buck Rogers story — is one of the icons of science-fiction art.

The November 1928 issue of AMAZING STORIES featured a cover illustration of Jupiter as seen from Ganymede. It was done to accompany Frank J. Brueckel’s story, “The Moon Men.” The artwork was one of the last covers created by Frank R. Paul for the Gernsback version of AMAZING. Paul would return to the magazine in 1939 — after Ziff-Davis had become its publisher, painting over fifty back covers for AMAZING STORIES and its companion, FANTASTIC ADVENTURES.