Not only will we be celebrating science fiction’s “Golden Year of 1939” and “75 Years of Fantastic Fiction,” PulpFest 2014 intends to pay homage to “The Weird-Menace Magazines of 1934.” Called shudder pulps, these magazines experienced a brief period of popularity that began in late 1933 and ran until 1941, when a concerted reform movement brought an end to the genre.

Not only will we be celebrating science fiction’s “Golden Year of 1939” and “75 Years of Fantastic Fiction,” PulpFest 2014 intends to pay homage to “The Weird-Menace Magazines of 1934.” Called shudder pulps, these magazines experienced a brief period of popularity that began in late 1933 and ran until 1941, when a concerted reform movement brought an end to the genre.

Noted pulp authority Don Hutchison, author of The Great Pulp Heroes, has contributed a look at the weird-menace genre, “Pulp Horrors of the Dirty Thirties,” to this year’s issue of The Pulpster, our award-winning program book. Offered here are just a few of the gory details.

Pulp Horrors of the Dirty Thirties: An Excerpt

Back in the days of bread lines and hobo jungles, millions of readers found escapist thrills in the pages of cheaply produced magazines printed on rough pulpwood paper. Pulp magazines catered to every imaginable reading taste from detective yarns to pirate stories, from jungle adventures to science fiction and even romance. But the wildest of them all were the notorious horror tomes known collectively as the shudder pulps.

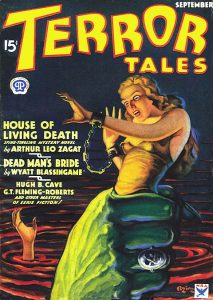

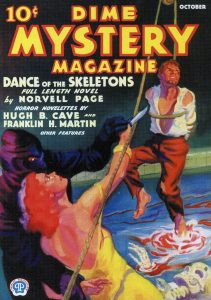

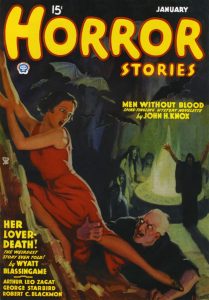

The so-called “shudder” or “weird-menace” titles were a blood-red splash of color in the grey days of the Great Depression. They announced their monthly wares with circus-poster-style covers featuring voluptuous under-dressed beauties being pursued by hordes of leering lunatics as bent as boomerangs. Their promise: cheap thrills, and plenty of them.

In their nightmare universe it was always a dark and stormy night. Tethered damsels suffered in the clutches of fiends such as hell-mad surgeons, warped scientists, and masked and cowled cultists, eagerly abetted by legions of demented dwarfs and horny hunchbacks. They stripped, whipped, and boiled their curvaceous victims with the enthusiasm of medieval inquisitors. Even the requisite rock-jawed heroes of these stories suffered a purgatory of horrors in order to rescue their brutally treated fair maidens.

In their nightmare universe it was always a dark and stormy night. Tethered damsels suffered in the clutches of fiends such as hell-mad surgeons, warped scientists, and masked and cowled cultists, eagerly abetted by legions of demented dwarfs and horny hunchbacks. They stripped, whipped, and boiled their curvaceous victims with the enthusiasm of medieval inquisitors. Even the requisite rock-jawed heroes of these stories suffered a purgatory of horrors in order to rescue their brutally treated fair maidens.

The weird-menace magazines lasted for but a few brief years, roughly from 1933 to 1941, when the actions of blue-nosed watchdogs helped propel them from the market. In contrast to previous horror magazines with their literate but fusty eldritch mysteries, the new breed of terror pulps dared go where no newsstand magazines had gone before. These few magazines were largely responsible for the low opinion people held (and still hold) of the entire pulp fiction field. Many dealers sold them under the counter, and New York’s mayor Fiorello La Guardia singled them out when he warned the pulp publishers to clean up their act or get out of town.

With stories written to a strict formula by seasoned pros, shudder pulps featured some of the most unashamedly lurid fiction and art ever produced for the newsstands of middle America. Each month they announced their presence with covers illustrating in chromatic detail the titillating promise of stories like: “Flesh For the Goat Man,” “The Corpse Wants Your Widow,” “Food for the Fungus Lady,” “Mate For the Thing in the Box,” and “Summer Camp for Corpses.”

The first of the new breed of fiction mags, Dime Mystery, lurched onto the newsstands in October of 1933. It was the brainchild of Popular Publication’s resourceful young publisher Henry Steeger and took off like skyrockets. Popular Publications lost little time in producing not one, but two companion monthlies: Terror Tales, followed by Horror Stories.

The first of the new breed of fiction mags, Dime Mystery, lurched onto the newsstands in October of 1933. It was the brainchild of Popular Publication’s resourceful young publisher Henry Steeger and took off like skyrockets. Popular Publications lost little time in producing not one, but two companion monthlies: Terror Tales, followed by Horror Stories.

Readers responded in large numbers to the lure of these purple prose set-ups and the inevitable pay-off in hell-spawned horrors. Soon, other publishers rushed into print with similar books of their own. Chief among them was publisher Ned Pines, whose Thrilling Mystery was a clone of Popular’s Dime Mystery. Believing that the public can never get too much of a bad thing, more newcomers tested the limits of sensationalism. There was Ace Mystery, Eerie Mysteries, Eerie Stories, Mystery Novels and Short Stories, Mystery Tales, Spicy Mystery Stories, Uncanny Tales, and others.

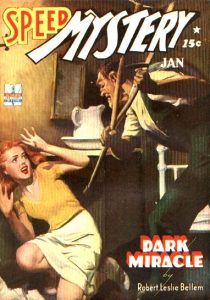

In the early 1940s there developed a public rejection of the permissiveness and thrill-seeking of the thirties. When New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia threatened to rid his city of sex-and-sadism magazines, publishers retrenched in fear of losing newsstand sales as well as their U. S. postal mailing privileges. As shudder pulp stalwart Bruno Fischer described it “Clean-up organizations started throwing their weight around and gave editors jitters, and artists and writers were instructed to put panties and brassieres on the girls.”

Dime Mystery was retooled as a straight mystery magazine. Spicy Mystery soldiered on for awhile, but was then re-titled Speed Mystery. Terror Tales and Horror Stories were shut down in 1941. Pulp fiction’s bloody reign of terror had ended, not with a bang but with a whimper. Unfortunately, in discarding key ingredients of their appeal, the magazines failed to develop new innovations, much less new readers. And, with the coming of World War II, the extent of human madness and misery could no longer be viewed–much less enjoyed–as mere fiction. In a more innocent time, it was thought that the brand of horror perpetrated by the fiends of the shudder pulps was purely imaginary. Now people knew that such things–and worse–were possible.

Dime Mystery was retooled as a straight mystery magazine. Spicy Mystery soldiered on for awhile, but was then re-titled Speed Mystery. Terror Tales and Horror Stories were shut down in 1941. Pulp fiction’s bloody reign of terror had ended, not with a bang but with a whimper. Unfortunately, in discarding key ingredients of their appeal, the magazines failed to develop new innovations, much less new readers. And, with the coming of World War II, the extent of human madness and misery could no longer be viewed–much less enjoyed–as mere fiction. In a more innocent time, it was thought that the brand of horror perpetrated by the fiends of the shudder pulps was purely imaginary. Now people knew that such things–and worse–were possible.

If you’d like to read the unabridged version of Don Hutchison’s article, it will be appearing in the PulpFest 2014 program book, The Pulpster. You’ll find ordering instructions at the bottom of our post entitled “To Infinity and Beyond.” It was featured on our home page on June 15th.

To learn more about the images used in this post, click on the illustrations.